We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

PAY THE MAN, SHIRLEY

John O’Hara ripped off his mama.

In February 2019, John pled guilty to wire fraud and bank fraud for stealing over $300,000 from his aged mother, whose finances he was managing. She died a few weeks after his guilty plea – from a broken heart, perhaps? – but she nonetheless passed on leaving her entire estate to her boy John.

In February 2019, John pled guilty to wire fraud and bank fraud for stealing over $300,000 from his aged mother, whose finances he was managing. She died a few weeks after his guilty plea – from a broken heart, perhaps? – but she nonetheless passed on leaving her entire estate to her boy John.

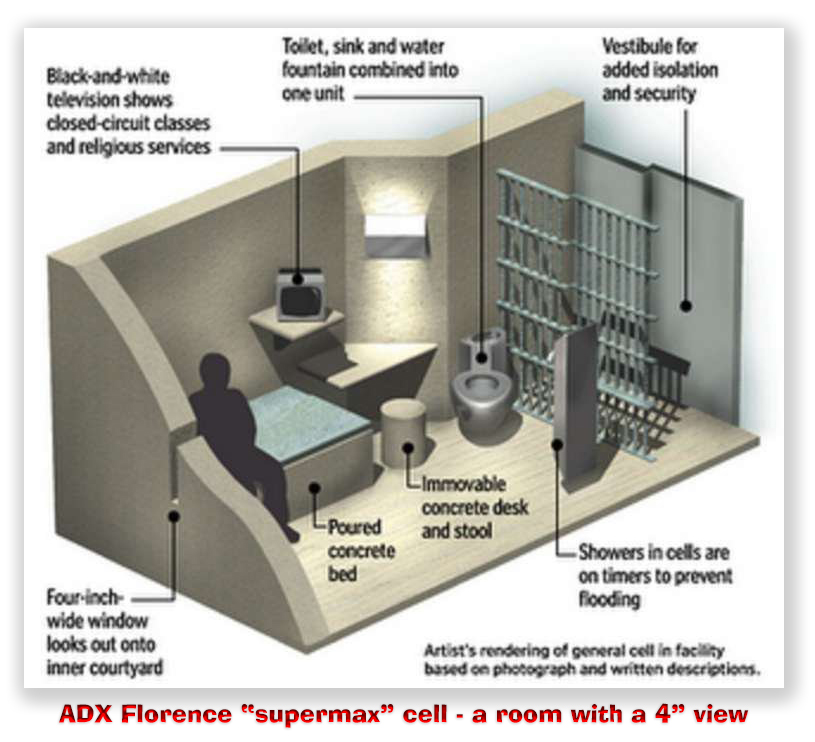

At sentencing, the Court ordered John to do 26 months in prison and to pay $332,150 or so in restitution to his mother’s estate. Despite knowing the restitution that John paid to the estate would end up back in his own pocket, the government did not object to the restitution order.

John was released in May 2021 but – contrary to his conditions of supervised release – had paid no restitution since his release from prison. Normally, a supervised releasee would be violated for such a history of noncompliance with release conditions, but the district court was realistic. In May 2023, it issued an order noting that while John had failed for two years “to pay any portion of the restitution as directed by the Court,” still,

inasmuch as the defendant would be the recipient of any restitution he might pay in the future, it is hereby ordered that, within fourteen days, the United States is directed to state its position regarding whether the defendant should be discharged from his existing restitution obligation.

The government suggested that since it couldn’t see the defendant being allowed to pay himself, the Court should substitute the Crime Victims Fund in place of his mother’s estate. John, of course, suggested that the court just forget the whole restitution thing.

The district court ruled that “allowing a perpetrator to effectively receive his own restitution would have the effect of nullifying a court’s restitution order and circumventing Congress’ intent to require mandatory restitution under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act.” It thus amended the judgment to require John to pay the $332,150 to the Crime Victims Fund.

John appealed, and this week, the 6th Circuit reversed the amended judgment, saying (albeit reluctantly), “Pay the man, Shirley. And that man is yourself.”

After a court imposes a sentence, the Circuit observed, it has no authority to change the sentence “unless such authority is expressly granted by statute.” Because a restitution order is a part of the sentence, if a court wants to change a restitution order, “it must point to express statutory authorization to do so.”

While 18 USC § 3664 expressly allows modification of restitution order, it lists only “a handful of ways a restitution order may be altered.” It may be amended if the victim’s losses are not ascertainable at sentencing, adjusted due to a defendant’s changed economic circumstances, or modified if the defendant is resentenced.

While 18 USC § 3664 expressly allows modification of restitution order, it lists only “a handful of ways a restitution order may be altered.” It may be amended if the victim’s losses are not ascertainable at sentencing, adjusted due to a defendant’s changed economic circumstances, or modified if the defendant is resentenced.

None of these, the 6th said, apply here, “so the district court could not use them to amend the judgment.”

The Circuit understood the district court’s motivation. “This is a case where a court may be tempted to elide the statute’s text to do what makes practical sense within the spirit and confines of the MVRA,” the appellate court wrote. “But even given the MVRA’s laudable goals, a court does not have discretion to ignore the statutory limits on modifying a final restitution order.”

This is not to say that the courts are without power to deny John his plan to pay himself restitution. The 6th included a detailed footnote observing that Kentucky statute § 381.280(2) excludes people from inheriting the results of their wrongdoing. “We leave the statute’s application to state courts,” the appellate decision states. “We only note that such a statutory scheme seems to fit the occasion and reiterate that it would be in the power of the probate court to apply its terms were the estate to be reopened and receive any money.”

The Circuit’s message: Justice may yet triumph, Mr. O’Hara.

United States v. O’Hara, Case No. 23-5695, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 20983 (6th Cir. Aug. 20, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root