We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

6TH CIRCUIT EXPANDS HAVIS HOLDING TO FRAUD GUIDELINES

The 6th Circuit expanded its groundbreaking United States v. Havis decision to white-collar cases last week in a fraud decision that suggests a Guidelines defense for a lot of defendants.

The devil’s in the details. Most federal crimes carry a statutory penalty of from a minimum to a maximum sentence. Distributing 100 grams of powder cocaine, for example, carries a punishment of zero-to-20 years. Where precisely within that range a judge should sentence a defendant is where the Sentencing Guidelines come in.

The devil’s in the details. Most federal crimes carry a statutory penalty of from a minimum to a maximum sentence. Distributing 100 grams of powder cocaine, for example, carries a punishment of zero-to-20 years. Where precisely within that range a judge should sentence a defendant is where the Sentencing Guidelines come in.

The Guidelines consider a variety of factors in determining an offense level – such as, in our cocaine example, the quantity of drugs, whether the defendant supervised other people, lied to the authorities, had a weapon in hand while dealing the powder, entered a guilty plea, and so on. Then, the defendant gets points for prior convictions (varying – drunk driving doesn’t score like a prior bank robbery, for instance), and a sentencing range is determined from a matrix with the criminal history as the abscissa and the total offense level as the ordinate.

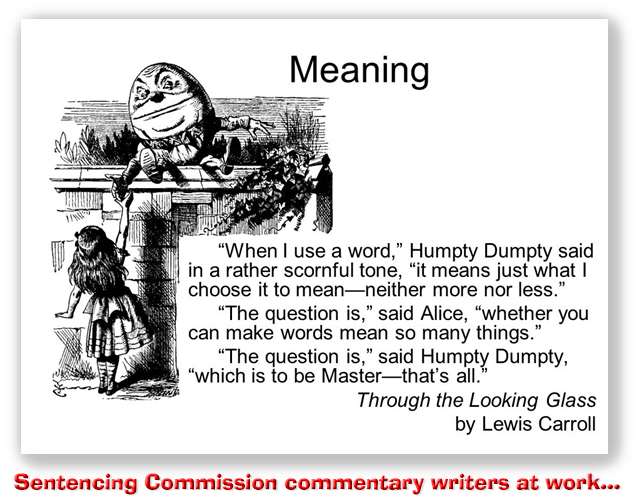

The Guidelines are written by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, a judicial branch agency established by Congress. When a Guideline is written or amended, the provision is adopted by the Commission. Congress then has six months to either reject the change (kind of a legislative veto) or do nothing. If Congress does nothing, the Guideline provision is deemed adopted.

All of which brings us to Havis. I wrote about this decision in summer 2019 (way back before the pandemic). Each Guideline has appended to it commentary, which may be Application Notes – instructing a court on how to apply the provision – or just background. This is often useful stuff, but – unlike the Guideline itself – commentary is added by the Commission but not subject to Congressional approval.

In Havis, the 6th Circuit was considering a particular piece of commentary attached to USSG § 4B1.2. That Guideline defined “drug trafficking” crime in detail, but it did not specify that an attempt to commit a drug trafficking crime (or, for that matter, to conspire to commit such a crime), was included in the definition. No problem for the Commission staff – it just wrote into the commentary that attempts and conspiracies were included.

In Havis, the 6th Circuit was considering a particular piece of commentary attached to USSG § 4B1.2. That Guideline defined “drug trafficking” crime in detail, but it did not specify that an attempt to commit a drug trafficking crime (or, for that matter, to conspire to commit such a crime), was included in the definition. No problem for the Commission staff – it just wrote into the commentary that attempts and conspiracies were included.

“Not so fast,” the 6th Circuit said in Havis. The Commission is not allowed to add to a Guideline definition approved by Congress with its own gloss. Sure, the definition could be expanded to include attempts and conspiracies, but to do so, it had to be approved by the Commission and subjected to Congressional oversight first.

Whew! Time for a break. Get a cup of coffee and then let’s resume.

Last week, the 6th Circuit took up the case of Jennifer Riccardi, a postal employee who pled guilty to stealing 1,505 gift cards from the mail.

Jen worked in the Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. Postal Service distribution center (Motto: ‘Where Quality is a Slogan, and Chaos is a Lifestyle‘). In September 2017, an Ohioan mailed a $25 Starbucks gift card from Mentor, Ohio, to nearby Parma. The card never arrived. The sender complained to the U.S. Postal Service, which – in perhaps the only recorded instance in history – took the complaint seriously. opened an investigation. Investigators learned that supervisors at a Cleveland distribution center had been finding lots of opened mail in the processing area. Now you’d think this would have caused some puzzlement, but it did not until investigators followed the trail to Jen. When confronted, she admitted that she had been stealing mail that might contain cash or gift cards for quite some time. A search of her home uncovered over 100 pieces of mail that she had taken just that day, $42,102 in cash, and 1,505 gift cards. The gift cards were laid out on the floor organized by the 230 or so merchants at which they could be redeemed. Sad she hadn’t used such organizational skills at the Postal distribution center.

Jen worked in the Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. Postal Service distribution center (Motto: ‘Where Quality is a Slogan, and Chaos is a Lifestyle‘). In September 2017, an Ohioan mailed a $25 Starbucks gift card from Mentor, Ohio, to nearby Parma. The card never arrived. The sender complained to the U.S. Postal Service, which – in perhaps the only recorded instance in history – took the complaint seriously. opened an investigation. Investigators learned that supervisors at a Cleveland distribution center had been finding lots of opened mail in the processing area. Now you’d think this would have caused some puzzlement, but it did not until investigators followed the trail to Jen. When confronted, she admitted that she had been stealing mail that might contain cash or gift cards for quite some time. A search of her home uncovered over 100 pieces of mail that she had taken just that day, $42,102 in cash, and 1,505 gift cards. The gift cards were laid out on the floor organized by the 230 or so merchants at which they could be redeemed. Sad she hadn’t used such organizational skills at the Postal distribution center.

Most of the cards were worth about $35.00, for a total value of about $47,000. Under § 2B1.1 of the Guidelines, Jen’s offense level based on the amount of the loss, something § 2B1.1 does not define. But the Guidelines commentary to § 2B1.1 helpfully “instructs that the loss shall be not less than $500.00 for each unauthorized access device, a phrase that… covers stolen gift cards. Applying that definition, the district court pumped Jen’s loss up from $47,000 (which what the stolen cards were actually worth) to $752,500 (that is, 1,505 cards multiplied by $500.00 per card).

“So what?” you might ask. The ‘so what’ is that Jen’s Guidelines offense level depends a lot on the amount of loss. A loss of $47,000 elevated her range by six levels. But if you pretend the loss was $752,500 – and it would really be pretending – her offense level would shoot up 14 levels. In Jen’s case, the difference was a sentencing range of 10-16 months and a range of 46-57 months. The district court gave Jen 56 months.

Based on its Havis holding, the 6th rejected the loss calculation and sentence. Havis held “guidelines commentary may only interpret, not add to, the guidelines themselves… And even if there is some ambiguity in 2B1.1’s use of the word “loss,” the commentary’s bright-line rule requiring a $500 loss amount for every gift card does not fall “within the zone of ambiguity” that exists. So this bright-line rule cannot be considered a reasonable interpretation of — as opposed to an improper expansion beyond — 2B1.1’s text.”

Based on its Havis holding, the 6th rejected the loss calculation and sentence. Havis held “guidelines commentary may only interpret, not add to, the guidelines themselves… And even if there is some ambiguity in 2B1.1’s use of the word “loss,” the commentary’s bright-line rule requiring a $500 loss amount for every gift card does not fall “within the zone of ambiguity” that exists. So this bright-line rule cannot be considered a reasonable interpretation of — as opposed to an improper expansion beyond — 2B1.1’s text.”

Ohio State University law prof Doug Berman thinks this case is a big deal. He wrote in his Sentencing Law and Policy blog, “the fraud guideline is not the only one important part of the federal sentencing guideline with an intricate set of commentary instructions that might be challenged as full of ‘improper expansions.’ I sense a growing number of litigants and courts are starting to hone on potentially problematical guideline commentary and that some variation of this issue with be getting to the U.S. Supreme Court before too long. In the meantime, defense attorneys would be wise to challenge (and preserve arguments around) any application of guideline commentary that even might be viewed as ‘expansionary’.”

United States v. Riccardi, Case No 19-4232, 2021 U.S. App. LEXIS 6163 (6th Cir. March 3, 2021)

Sentencing Law and Policy, Did a Sixth Circuit panel largely decimate the federal sentencing fraud guidelines (and perhaps many others)? (March 5)

– Thomas L. Root