We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THE TWO FACES OF HOBBS

Two cases decided in the past few weeks illustrate the strange world of Hobbs Act robbery.

The Hobbs Act, a post-war legacy of Congressman Sam Hobbs (D-Alabama) federalized robbery of the corner candy store. Sam was a man of his time, close friends of J. Edgar Hoover (and sponsor of a bill that would have let the FBI wiretap anyone suspected of a felony, which ultimately did not pass).

The Hobbs Act, a post-war legacy of Congressman Sam Hobbs (D-Alabama) federalized robbery of the corner candy store. Sam was a man of his time, close friends of J. Edgar Hoover (and sponsor of a bill that would have let the FBI wiretap anyone suspected of a felony, which ultimately did not pass).

The Hobbs Anti-Racketeering Act of 1946 amended the Anti-Racketeering Act of 1934 after the Supreme Court held in United States v. Teamsters Local 807 that Congress meant to exempt union extortion from criminal liability. Congress did not so intend, and Sam Hobbs sponsored a bill that made sure the Court got the message.

Like its predecessor, the Hobbs Act prescribes heavy criminal penalties for acts of robbery or extortion that affect interstate commerce. The courts have interpreted the Hobbs Act broadly, requiring only a minimal effect on interstate commerce to justify the exercise of federal jurisdiction. That Clark bar you stole at gunpoint? It was made over in Altoona, Pennsylvania, by the Boyer Candy Co. Inasmuch as you robbed it from a confectioner in Podunk Center, Iowa, your robbery affected interstate commerce. Presto – a Hobbs Act robbery.

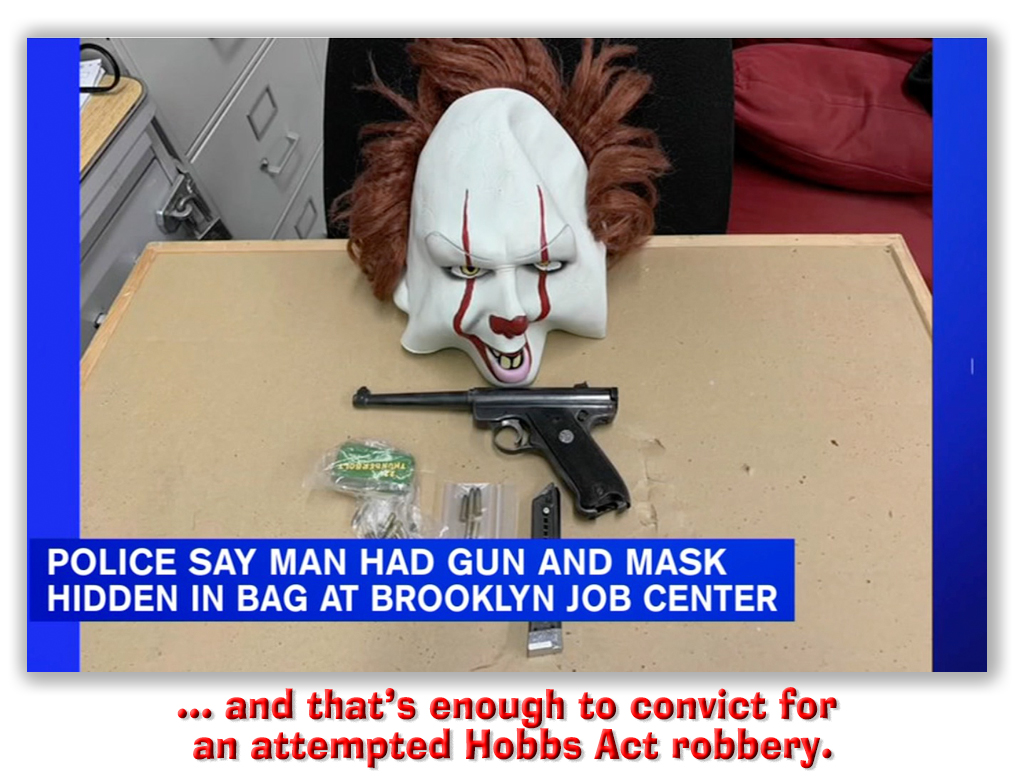

The Hobbs Act has been used as the basis for federal prosecutions in situations not apparently contemplated by Congress in 1946. Just ask Earl McCoy.

The Hobbs Act has been used as the basis for federal prosecutions in situations not apparently contemplated by Congress in 1946. Just ask Earl McCoy.

Earl rode around in the car while his brothers committed armed home invasions, stealing TVs and the such from Harry and Harriet Homeowner at gunpoint. Convicted of Hobbs Act robbery, Hobbs Act conspiracy, attempted Hobbs Act robbery and of four counts of using a gun in the commission of the crimes, Earl got sentenced to 135 years.

That’s only 15 years less than Bernie Madoff got for a $65 billion swindle, proving Earl was probably in the wrong business. Of course, Bernie didn’t use a gun. It was the gun that got Earl, five stacked 18 USC § 924(c) counts that added 107 years to his sentence. The First Step Act changed the stacking law, so the same offense would net Earl only 35 years today, still substantial time but at least servable in a normal lifetime.

Ernie appealed his conviction, arguing that the attempted robberies, the conspiracy, and aiding and abetting could not support 18 USC 924(c) convictions. Ten days ago, the 2nd Circuit gave him a split decision.

The 2nd agreed that after United States v. Davis, Hobbs Act conspiracy no longer supports a § 924(c) conviction. No surprise there. But the Circuit held that attempted Hobbs Act robbery and, for that matter, aiding and abetting a Hobbs Act robbery, was a crime of violence that supports a § 924(c) conviction.

The 2nd agreed that after United States v. Davis, Hobbs Act conspiracy no longer supports a § 924(c) conviction. No surprise there. But the Circuit held that attempted Hobbs Act robbery and, for that matter, aiding and abetting a Hobbs Act robbery, was a crime of violence that supports a § 924(c) conviction.

Earl argued that one could attempt a Hobbs Act robbery without ever using force. After all, scoping out a store to rob while carrying a gun is enough to constitute an attempt, and no violence was ever used. Doesn’t matter, the 2nd said. To be guilty of Hobbs Act attempted robbery, a defendant necessarily must intend to commit all of the elements of robbery and must take a substantial step towards committing the crime. Even if a defendant’s substantial step didn’t itself involve the use of physical force, he or she must necessarily have intended to use physical force and have taken a substantial step towards using physical force. That constitutes “attempted use of physical force” within the meaning of § 924(c)(3)(A).

For aiding-and-abetting to be enough to convict someone of a crime, the underlying offense must have been committed by someone other than the defendant, and the defendant must have acted with the intent of aiding the commission of that underlying crime. An aider and abetter is as guilty of the underlying crime as the person who committed it.

Because an aider and abettor is responsible for the acts of the person who committed the crime, the Circuit held, “an aider and abettor of a Hobbs Act robbery necessarily commits all the elements of a principal Hobbs Act robbery.”

Earl will get 25 years knocked off his sentence, leaving him with a mere 110 years to do. As for whether “attempts” to commit a crime of violence is itself a crime of violence, that question may not be settled short of the Supreme Court.

Earl will get 25 years knocked off his sentence, leaving him with a mere 110 years to do. As for whether “attempts” to commit a crime of violence is itself a crime of violence, that question may not be settled short of the Supreme Court.

But the Hobbs Act has a split personality: it is not a crime of violence for all purposes. In the 4th Circuit, Rick Green pled to Hobbs Act robbery, with an agreed sentence of 120 months. But the presentence report used the Hobbs Act robbery as a crime of violence to make him a Guidelines career offender, with an elevated 151-188 month sentencing range. At sentencing, Rick argued Hobbs Act robbery was not a crime of violence under the Guidelines “career offender” definition. His sentencing judge disagreed.

But last week, the 4th Circuit sided with Rick. Applying the categorical approach, the Circuit observed that Hobbs Act robbery can be committed “by means of actual or threatened force, or violence, or fear of injury, immediate or future,” to a victim’s person or property.” The 4th said, “this definition, by express terms, goes beyond the use of force or threats of force against a person and reaches the use of force or threats of force against property, as well… So to the extent the Guidelines definition of “crime of violence” requires the use of force or threats of force against persons, there can be no categorical match.”

Thus, Rick was not a “career offender,” and will get resentenced to his agreed-upon 120 months.

United States v. McCoy, Case No 17-3515(L), 2021 US App. LEXIS 11873 (2nd Cir Apr 22, 2021)

United States v. Green, Case No 19-4703, 2021 US App. LEXIS 12844 (4th Cir Apr 29, 2021)

– Thomas L. Root

There is little doubt that this issue, and probably the whole “attempt” furball, is headed for the Supreme Court.

There is little doubt that this issue, and probably the whole “attempt” furball, is headed for the Supreme Court.