We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SCOTUS SCHEDULES ARGUMENT ON TWO CRIMINAL CASES OF NOTE

The Supreme Court has issued its February oral argument schedule, including two cases of substantial interest to federal defendants and prisoners.

The two arguments actually fall the first week of March, not in February… but then this is the Supreme Court, where the last week of next June will still be “October Term 2025.” Nevertheless, we can be confident that before the cherry blossoms bloom along the Tidal Basin, we may have some idea of the high court’s thinking on two consequential criminal cases now before it.

The two arguments actually fall the first week of March, not in February… but then this is the Supreme Court, where the last week of next June will still be “October Term 2025.” Nevertheless, we can be confident that before the cherry blossoms bloom along the Tidal Basin, we may have some idea of the high court’s thinking on two consequential criminal cases now before it.

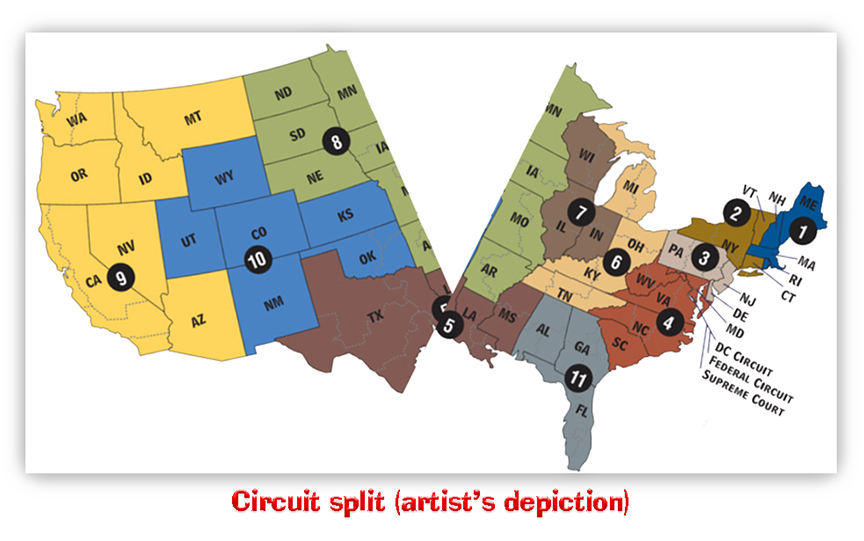

The cases: First, the one not getting much press but arguably the more important of the two is Hunter v. United States, a case that asks whether a federal appeals court properly dismissed a Texas man’s appeal of a mandatory-medication condition when he had waived his right to appeal as part of his plea agreement, but the judge who imposed the condition told him that he had a right to appeal.

The importance is this: Something like 94% of federal criminal cases end in guilty pleas, and virtually all of those pleas are entered pursuant to a written plea agreement between the defendant and the government. And virtually all of those agreements have the defendant agreeing to waive his or her rights to appeal, to file post-conviction attacks on their conviction and sentences, and to give up other rights – such as to seek compassionate release or even bring a Freedom of Information Act request for records from the government.

The Hunter issues before the Supreme Court include what, if any, are the permissible exceptions to waiver in a plea agreement, now generally recognized as only being claims of ineffective assistance of counsel or that the sentence exceeds the statutory maximum. A second issue is whether an appeal waiver applies when the sentencing judge advises the defendant that he or she has a right to appeal and the government does not object.

The Hunter issues before the Supreme Court include what, if any, are the permissible exceptions to waiver in a plea agreement, now generally recognized as only being claims of ineffective assistance of counsel or that the sentence exceeds the statutory maximum. A second issue is whether an appeal waiver applies when the sentencing judge advises the defendant that he or she has a right to appeal and the government does not object.

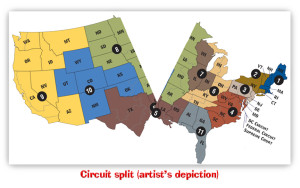

The Supreme Court case getting more attention is United States v. Hemani, in which the government is challenging a 5th Circuit ruling that 18 USC § 922(g)(3) – that prohibits an “unlawful user” of a controlled substance from possessing a gun – violates the 2nd Amendment as applied to the defendant. Mr. Hemani was a regular marijuana user but was not high while in physical possession of his handgun.`

Law Professor Joel Johnson, a former Supreme Court litigator with the Dept of Justice, recently argued in a SCOTUSBlog post that the Supreme Court could easily dispose of the Hemani case by relying on the rule of lenity instead of the 2ndAmendment. He said, “If the court decides that the law applies only to people who are armed while intoxicated, the 2nd Amendment concerns largely vanish. There is stronger historical support for disarming someone who is high – and thus not of sound mind – than there is for disarming someone who happened to smoke a joint last weekend but is no longer impaired.”

Also in a SCOTUSBlog post, NYU Law Professor Danial Harawa argued for a revival of the rule of lenity:

Congress has enacted thousands of criminal laws, many written broadly and enforced aggressively. With an overly bloated criminal code, lenity should function as a meaningful check – a reminder that punishment must rest on clear legislative authorization… At bottom, the rule of lenity is about who bears the risk of uncertainty in the criminal law. For most of the court’s history, that risk fell on the government. When Congress failed to speak clearly, defendants were entitled to the benefit of the doubt. If it wanted, Congress could rewrite the law to clarify its reach. There is no cost for congressional imprecision, however, and thus no real need for Congress to legislate carefully and clearly. When lenity is weakened, the cost of ambiguity shifts from the government to defendants, and the result is more defendants. Given the pedigree and importance of this rule, the Supreme Court needs to resolve when the rule applies sooner rather than later.

Second Amendment advocates and scholars hope that Hemeni will advance the 2nd Amendment debate begun by Heller, Bruen, and Rahimi. But even if it does not, it may provide some enduring guidance on the rule of lenity, an issue of less sexiness but perhaps more import to criminal law.

Second Amendment advocates and scholars hope that Hemeni will advance the 2nd Amendment debate begun by Heller, Bruen, and Rahimi. But even if it does not, it may provide some enduring guidance on the rule of lenity, an issue of less sexiness but perhaps more import to criminal law.

SCOTUSblog, Court announces it will hear case on gun rights among several others in February sitting (January 2, 2026)

Hunter v. United States, Case No. 24-1063 (oral argument set for March 3, 2026)

United States v. Hemani, Case No, 24-1234 (oral argument set for March 2, 2026)

SCOTUSblog, An off-ramp for the court’s next big gun case (December 18, 2025)

SCOTUSblog, Reviving Lenity (December 26, 2025)

~ Thomas L. Root

Range

Range