We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

BOP DOES NOT HAVE TO WALK 500 MILES

There is not a single inmate in the federal prison system who would not be willing to walk, roll or crawl 500 miles to be home right now. Any no one on the outside is so hard-hearted that he or she cannot concede that housing inmates close enough to family to permit visits does not help with rehabilitation.

There is not a single inmate in the federal prison system who would not be willing to walk, roll or crawl 500 miles to be home right now. Any no one on the outside is so hard-hearted that he or she cannot concede that housing inmates close enough to family to permit visits does not help with rehabilitation.

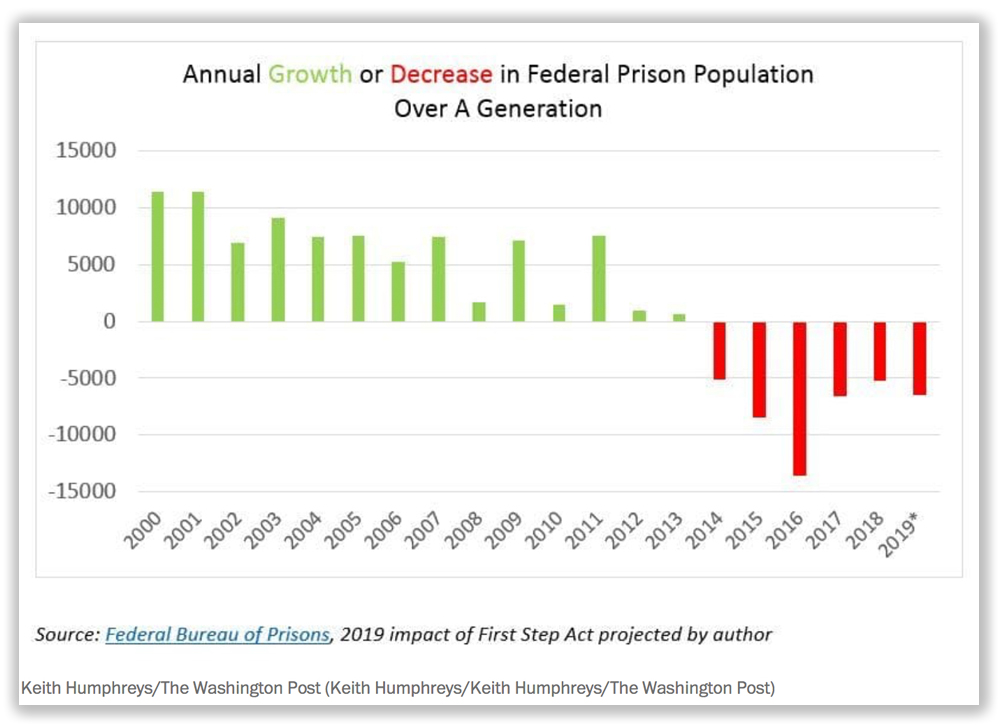

For those reasons (if basic humanity were not enough), the First Step Act’s provision directing the Bureau of Prisons to “place the prisoner in a facility as close as practicable to the prisoner’s primary residence, and to the extent practicable, in a facility within 500 driving miles of that residence,” got a lot of coverage when the bill passed last December.

But just as the media buzz that 4,000-plus inmates were going to be dumped on America’s streets the day after the Act passed was wrong, the giddy hopes that inmates were about to be placed near to their families have been tempered by the realities of what the Act says and what the BOP is willing to do.

There is a usually a separation between promise and reality, sometimes a crack and sometimes a chasm. It is probably worthwhile, therefore, to explain just how little Sec. 601 of the First Step Act really promises families and inmates.

Sec. 601 modified 18 U.S.C. § 3621(b) to read that the BOP should try to place prisoners within 500 miles of home. That placement, however, is not required. In fact, it is subject to some pretty big exceptions, being subject to

(1) bed availability,

(2) the prisoner’s security designation,

(3) the prisoner’s programmatic needs,

(4) the prisoner’s mental and medical health needs,

(5) any request made by the prisoner related to faith-based needs,

(6) recommendations of the sentencing court, and

(7) “other security concerns of the” BOP.

Number 7 is a doozy. The placement need not violate a rule, or a BOP program statement, or even a local rule adopted by the sending or receiving prison. It just has to be a “concern.” Whatever that is, it is clearly something to be defined by the BOP.

Prior to the First Step Act, the BOP required that an inmate be at one institution for at least 18 months, and that he or she have 18 months without a disciplinary report (the BOP called it “clear conduct”) before he or she could be considered for a transfer. Often, transfers were denied because the inmate was deemed to need programming available at his or her current location, or occasionally, because the inmate had skills (a welder, for example, or a GED instructor) the current institution believed it needed to retain. When the transfer came (if it did), the inmate seldom ended up at the institution he or she desired.

Prior to the First Step Act, the BOP required that an inmate be at one institution for at least 18 months, and that he or she have 18 months without a disciplinary report (the BOP called it “clear conduct”) before he or she could be considered for a transfer. Often, transfers were denied because the inmate was deemed to need programming available at his or her current location, or occasionally, because the inmate had skills (a welder, for example, or a GED instructor) the current institution believed it needed to retain. When the transfer came (if it did), the inmate seldom ended up at the institution he or she desired.

In the wake of First Step, however, the BOP is still requiring that an inmate be at one institution for at least 18 months, and that he or she have 18 months without a disciplinary report (the BOP called it “clear conduct”) before he or she could be considered for a transfer. The BOP can still deny transfers for programming needs, perceived mental health needs (which, given the state of mental health treatment in the system, is a hoot), and for lack of bed space (which inmates from years past know to be an excuse that means whatever the BOP wants it to mean). Anything not covered by the foregoing can easily fall within the as-amorphous-as-Jello “security concerns” exception.

But they can’t do that, can they? Of course not. The injured inmate can always that the BOP to court…

Not so fast. Sec. 601 of the First Step Act added a free pass to the BOP: “Notwithstanding any other provision of law, a designation of a place of imprisonment under this subsection is not reviewable by any court.” So you don’t like what the BOP did? You can’t sue, can’t even bring a habeas corpus action, can’t even get on Judge Judy. The directive of § 601, detailed in its mandate and limitations, is completely undone by the last line of § 601, which tells the BOP, “if you don’t follow the law, no one is allowed to call you on it.”

Imagine a football game like that, where one team gets a yellow flag repeatedly, with each penalty being marched off for zero yards. Or, my preferred fantasy, a diet on which if you succumb to Wendy’s Peppercorn Mushroom Melt Triple with a side of Baconator Fries and large Coke, the 2,190 calories you consume would not keep you from dropping a pound a day. Sweet deal for the BOP.

Imagine a football game like that, where one team gets a yellow flag repeatedly, with each penalty being marched off for zero yards. Or, my preferred fantasy, a diet on which if you succumb to Wendy’s Peppercorn Mushroom Melt Triple with a side of Baconator Fries and large Coke, the 2,190 calories you consume would not keep you from dropping a pound a day. Sweet deal for the BOP.

If the BOP could be sued, the results would not be much different. Courts traditionally give substantial deference to the judgments of prison administrators. Even restrictive prison regulations are permissible if they are “‘reasonably related’ to legitimate penological interests. The BOP would say that its transfer restrictions – like 18 months of clear conduct – serve a legitimate penological goal. The courts, deferring to the BOP’s interpretation of the revised statute and its flexibility granted therein, would undoubtedly accept that.

Finally, even without prison-administration deference, courts generally defer to administrative agencies “when it appears that Congress delegated authority to the agency generally to make rules… and that the agency interpretation claiming deference was promulgated in the exercise of that authority.” This is called “Chevron deference,” and – while opponents hope to see the Supreme Court undo it at some point soon – it would easily apply to 18 U.S.C. § 3621(b) as to how the BOP measures bed availability, security concerns, programming needs and mental and physical health needs.

Finally, even without prison-administration deference, courts generally defer to administrative agencies “when it appears that Congress delegated authority to the agency generally to make rules… and that the agency interpretation claiming deference was promulgated in the exercise of that authority.” This is called “Chevron deference,” and – while opponents hope to see the Supreme Court undo it at some point soon – it would easily apply to 18 U.S.C. § 3621(b) as to how the BOP measures bed availability, security concerns, programming needs and mental and physical health needs.

So if the BOP ignores the Act’s 500-mile placement requirement, there is no remedy. Even if there were, BOP rules on transfer and the exceptions to closer-to-home would probably be unassailable.

Sec. 601, First Step Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-015, 132 Stat. 5208, 5238 (Dec. 21, 2018)

Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. NRDC, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984)

Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987)

– Thomas L. Root