We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

BOP FILING IN HABEAS CASE EXPLAINS INTERIM EARNED-TIME CREDIT POLICY

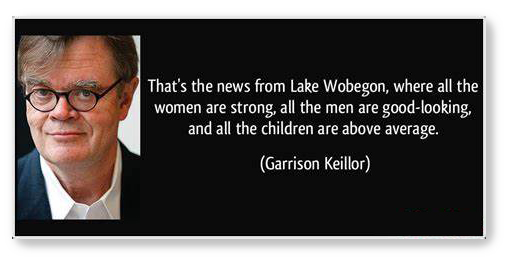

Back before Prairie Home Companion humorist Garrison Keillor had not yet been ‘canceled’ for lusting after women in his heart (or whatever the crime might have been), he created Lake Wobegon, a place where all the women were strong, the men were handsome, and the children were above average. The setting gave its name to the “Wobegon Effect,” a prejudice of superiority also known as illusory superiority.

Back before Prairie Home Companion humorist Garrison Keillor had not yet been ‘canceled’ for lusting after women in his heart (or whatever the crime might have been), he created Lake Wobegon, a place where all the women were strong, the men were handsome, and the children were above average. The setting gave its name to the “Wobegon Effect,” a prejudice of superiority also known as illusory superiority.

The BOP – due to sloth, being overwhelmed by events, or by design – may have instituted its own version of the phenomenon. Let’s call it the ‘ETC Effect.”

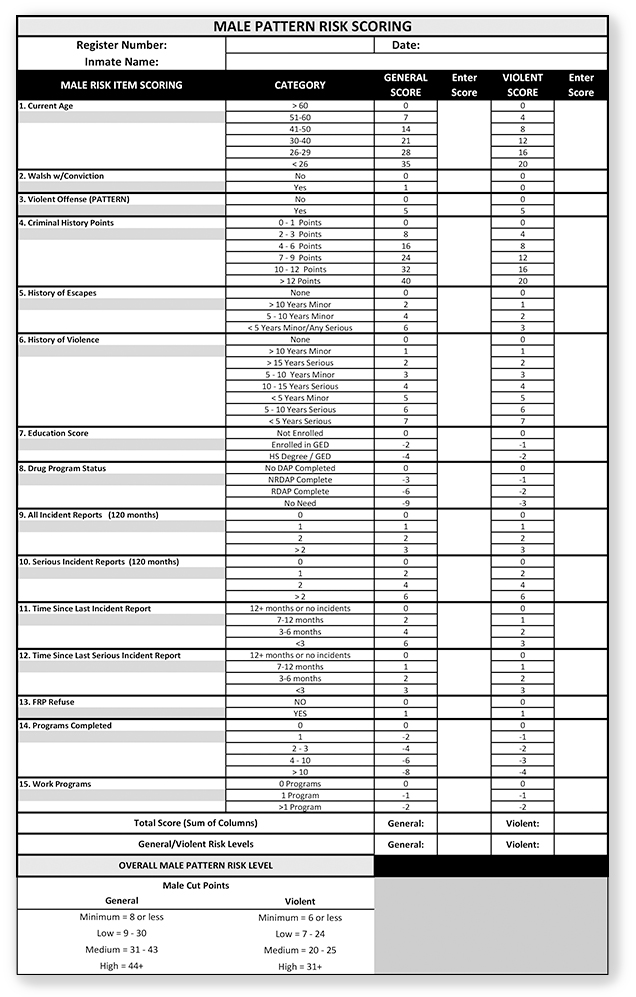

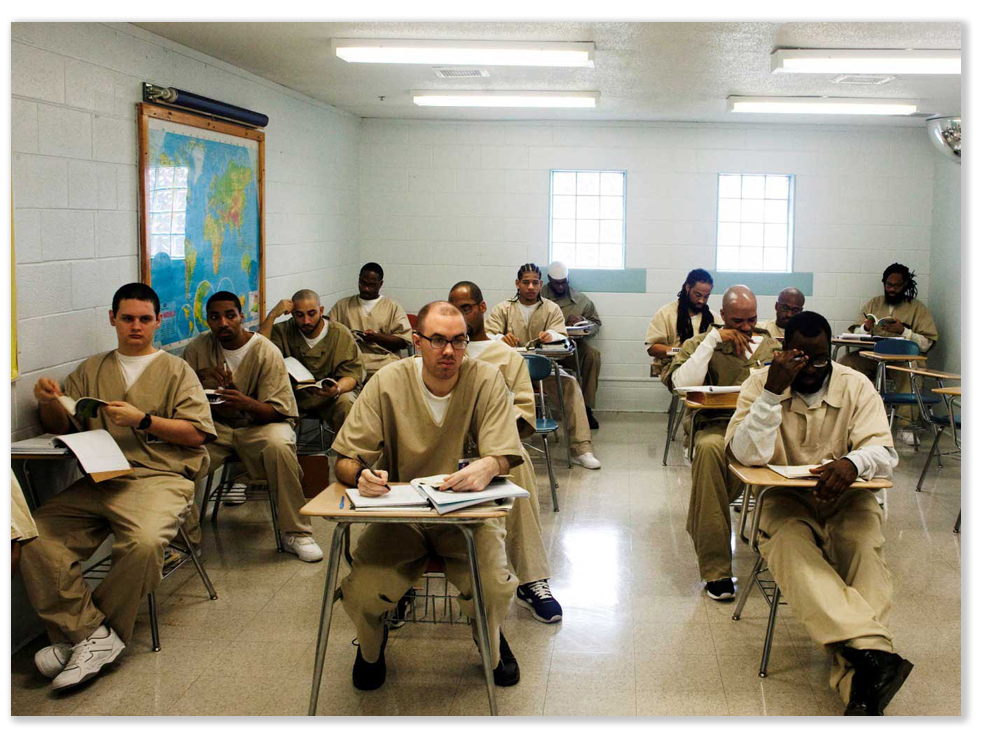

Recall that the First Step Act mandated that the BOP assess all inmates for their likelihood of recidivism and programming needs. Prisoners would then complete evidence-based recidivism reduction programming (EBRRs) that would address their needs and make them less likely to reoffend.

To encourage inmates to complete the programming, the BOP would award eligible inmates (and Congress exempted about half of all inmates from the program, probably to look good to those criminal-hating voters back home), First Step directed the BOP to issue ETCs. An inmate can earn from 10 to 15 days a month in ETCs for each 30 days spent in an EBRR or in pursuit of specified “productive activities.” The first 365 days’ worth of ETCs will reduce an eligible inmate’s sentence by up to a year. Any ETCs beyond that can be used for extra home confinement or halfway house.

When the BOP announced its final rules on EBRRs and ETCs in January, it specified that ETCs could be earned from the day First Step became law (December 21, 2018). This meant that a thundering herd of inmates who were close to their release date probably should already be home once their ETCs were applied. In fact, the BOP released a lot of inmates in the days and weeks following adoption of the rules. But since then, those still in prison have been complaining loudly that their ETC credits have not been applied.

Which brings us to Bob Stewart. Bob got his ETC calculation from the BOP last January, learning he had 75 days of credit as of Christmas Day 2021. But his release falls in October 2022. He argued that this imminent date makes continuous updating of his credits necessary. The BOP, which has been calculating ETCs inmate-by-inmate in a manual process, told Bob that he would not get an update until sometime in the future when the agency implemented a new “auto-calculation” programming.

Bob brought a habeas corpus action in federal court, arguing that had another 60 days coming as of the filing date in March 2022, and that he was continuing to earn days on a rolling basis until his release date.

The BOP moved to dismiss the action, arguing essentially that Bob would just have to wait for “auto-calc” like everyone else. Included with its filing was a fascinating declaration from Susan Giddings, a BOP official, explaining BOP interim policy.

Susan said that everyone got one manual calculation, and Bob had gotten his. After that, everyone had to wait until the BOP completed installation of its “auto-calculation application to BOP’s real-time information system (known as SENTRY) and full integration between SENTRY and BOP’s case management system (known as INSIGHT).” She estimated that “auto-calc” would be live by about August 1.

As interesting was her revelation that every ETC-eligible inmate was getting ETC credit from the day First Step passed or the inmate’s first day in prison, whichever was later. The grant appears to be independent of whether the inmate completed any programming during that time or not.

As interesting was her revelation that every ETC-eligible inmate was getting ETC credit from the day First Step passed or the inmate’s first day in prison, whichever was later. The grant appears to be independent of whether the inmate completed any programming during that time or not.

Bob’s district court was not impressed by the BOP’s reasoning that the law would just have to wait for the agency’s programmers. It ordered the BOP to recalculate Bob’s ETCs every 60 days, whether the “auto-calculation application” was working or not.

The Magistrate’s Report, adopted in full by the District Judge, said,

it is unclear when the automated system will be up and running. While it could be within the next 90 days, that is not guaranteed, and Respondent even hedges this statement with the caveat ‘absent unforeseen circumstances.’ Thus, the assertion that Stewart will receive these credits within the next couple months, i.e., in time for them to impact the remainder of his sentence, is speculative

Now for the interesting part. Susan revealed that the BOP is granting ETCs to every eligible inmate from the day First Step passed or the inmate’s first day in prison (whichever was later), whether any programs have been completed or not. I have had several inmates confirm this. One disgustedly told me, “There’s this guy in the unit who is asleep in his bunk all day and night, except for meals. He got the same number of ETCs – like 540 or so – everyone else got.”

What this means, in other words, is that every eligible inmate is successfully reducing his or her recidivism risk, every eligible inmate is excelling in productive activities, and – in fact – every eligible inmate is not only eligible, but above average.

What this means, in other words, is that every eligible inmate is successfully reducing his or her recidivism risk, every eligible inmate is excelling in productive activities, and – in fact – every eligible inmate is not only eligible, but above average.

Far be it from me to complain when any BOP program works to the benefit of inmates, but still, this is not how it is supposed to work. Someday, maybe someday soon, the music will stop. That will undoubtedly be an unpleasant jolt to the guy asleep in the top bunk… and to everyone else.

Stewart v. Snider, Case No. 1:22cv294, 2022 US Dist. LEXIS 100512 (N.D. Ala, May 10, 2022) (Magistrate’s Report)

Stewart v. Snider, Case No. 1:22cv294, 2022 US Dist. LEXIS 100482 (N.D. Ala, June 6, 2022( (District Court order)

Giddings Declaration, ECF 11-14, Case No. 1:22cv294, (N.D. Ala, filed Apr 29, 2022)

– Thomas L. Root