We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

LAST FRIDAY, SOME PRISONERS FROM SOMEWHERE WERE PERHAPS RELEASED (WHO CAN SAY?) AND DOJ ROLLED OUT PROPOSED RISK ASSESSMENT SYSTEM

Friday, July 19th was the day – a full 210 sunrises after President Trump signed the First Step Act into law. And, as required on that day, the Bureau of Prisons at long last credited federal inmates with the additional seven days per year promised them in the Act, and the Dept. of Justice released the risk assessment it proposes to have the Bureau of Prisons use to determine the likelihood that inmates will commit new offenses upon release.

A really big day… or was it?

Tie a Yellow Ribbon… Rahm Emmanuel may not have said it first, but he made it famous when he counseled his then-boss, President Obama, to never let a good crisis go to waste. DOJ dragged its feet in setting up a panel to implement the risk assessment model that is at the heart of the First Step Act’s earned time credit program (which lets federal prisoners earn extra time off their sentences for successfully completing programs that reduce recidivism). The Department as well fought hammer and tong to avoid crediting inmates with the extra good time Congress always meant them to have (but did not because DOJ interpreted a poorly-written statute as harshly as possible), an error corrected in First Step. And DOJ has opposed countless motions under the newly-retroactive Fair Sentencing Act for reductions of draconian prison terms.

Tie a Yellow Ribbon… Rahm Emmanuel may not have said it first, but he made it famous when he counseled his then-boss, President Obama, to never let a good crisis go to waste. DOJ dragged its feet in setting up a panel to implement the risk assessment model that is at the heart of the First Step Act’s earned time credit program (which lets federal prisoners earn extra time off their sentences for successfully completing programs that reduce recidivism). The Department as well fought hammer and tong to avoid crediting inmates with the extra good time Congress always meant them to have (but did not because DOJ interpreted a poorly-written statute as harshly as possible), an error corrected in First Step. And DOJ has opposed countless motions under the newly-retroactive Fair Sentencing Act for reductions of draconian prison terms.

Nevertheless, when faced with a July 19 deadline even it could not deny, DOJ did not miss the chance last Friday to trumpet its successes under First Step, chief among them that “over 3,100 federal prison inmates will be released from the BOP’s custody as a result of the increase in good conduct time under the Act. In addition, the Act’s retroactive application of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (reducing the disparity between crack cocaine and powder cocaine threshold amounts triggering mandatory minimum sentences) has resulted in 1,691 sentence reductions.”

So where was the flood of prisoner releases at the end of last week? As I heard from people at a dozen or more institutions, no one seemed to be leaving. This was corroborated by my own observation. With over 7,700 people on the LISA newsletter email list, I expected over 100 notifications from BOP on Friday of people whose Corrlinks email accounts were closed because they had been freed (such a notice is sent whenever someone is released and his or her Corrlinks account is closed). Instead, I got only 17 such messages.

So where was the flood of prisoner releases at the end of last week? As I heard from people at a dozen or more institutions, no one seemed to be leaving. This was corroborated by my own observation. With over 7,700 people on the LISA newsletter email list, I expected over 100 notifications from BOP on Friday of people whose Corrlinks email accounts were closed because they had been freed (such a notice is sent whenever someone is released and his or her Corrlinks account is closed). Instead, I got only 17 such messages.

Here’s what happened. As FAMM president Kevin Ring told the Wall Street Journal, most of the 3,100 inmates released Friday were already among the 8,300 BOP inmates in halfway houses or the 2,200 people on home confinement. Thus, alleged tsunami of prisoner releases – while reducing BOP population overall – was a barely-noticeable ripple at the institutions.

Plus, as Mother Jones magazine complained last week, not all of last Friday’s releasees got to go home. “Roughly a quarter of them are not United States citizens,” the magazine said, “and many will instead be sent straight to immigration detention to face deportation proceedings, which could take years.” As it turns out, USA Today reported, 900 released inmates were transferred to ICE or state authorities.

Inmate Sentence Recomputation More Tortoise Than Hare… More troubling are the numerous reports I have gotten from inmates and their families that BOP has not yet completed the recalculation of good time for most of the 151,000 inmates still in institutions. One inmates father reported that the BOP’s Grand Prairie, Texas, Designation and Sentence Computation Center told him that the agency is processing each inmate’s new time manually, and that it is able to complete no more than 5,000 a month.

Inmate Sentence Recomputation More Tortoise Than Hare… More troubling are the numerous reports I have gotten from inmates and their families that BOP has not yet completed the recalculation of good time for most of the 151,000 inmates still in institutions. One inmates father reported that the BOP’s Grand Prairie, Texas, Designation and Sentence Computation Center told him that the agency is processing each inmate’s new time manually, and that it is able to complete no more than 5,000 a month.

The reason for the glacial pace of recalculations is unclear, but it is hard to avoid noting that the BOP has had seven months to prepare for award of the additional good time. How the agency is unable, after seven months of preparation, to automate recalculation through a rather simple computer algorithm is puzzling.

I see a PATTERN Here… One of First Step’s marquee accomplishments is to establish a system that ranks each inmate’s risk of being a recidivist, and then tracks that risk throughout the inmate’s sentence. The inmate (unless he or she falls in one of the 60-plus “ineligible” categories) may take programs identified by the BOP as proven to reduce recidivism, and get up to 15 days credit a month for doing so. The credit may be used to reduce the length of his or her incarceration by up to 12 months, and beyond that, to earn the inmate extra halfway house or home confinement time.

I see a PATTERN Here… One of First Step’s marquee accomplishments is to establish a system that ranks each inmate’s risk of being a recidivist, and then tracks that risk throughout the inmate’s sentence. The inmate (unless he or she falls in one of the 60-plus “ineligible” categories) may take programs identified by the BOP as proven to reduce recidivism, and get up to 15 days credit a month for doing so. The credit may be used to reduce the length of his or her incarceration by up to 12 months, and beyond that, to earn the inmate extra halfway house or home confinement time.

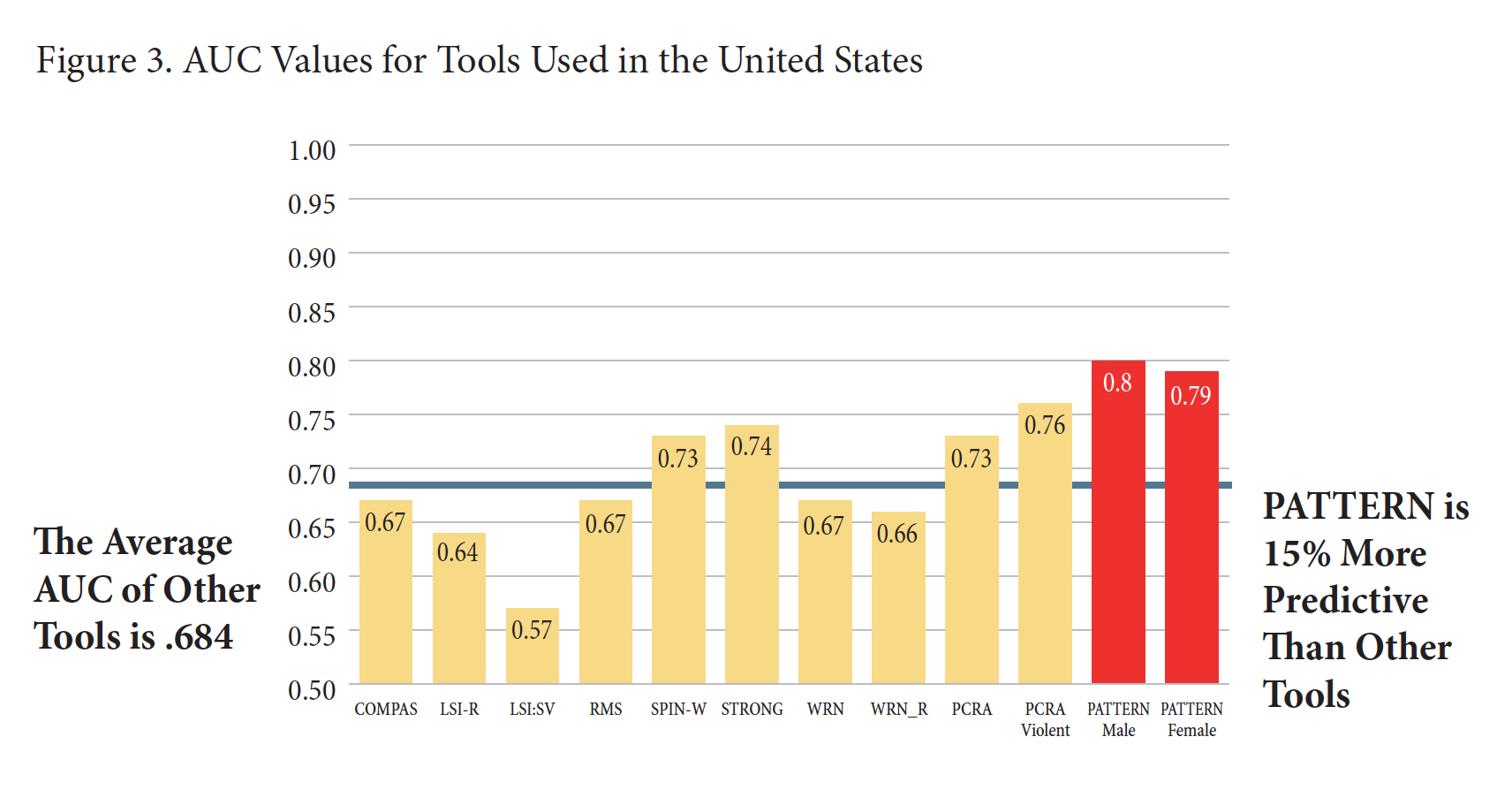

Before the program is implemented, the DOJ must adopt a system to rank prisoners’ recidivism risk. On the last afternoon of the 210-day period First Step gave DOJ for doing so, it unveiled its proposed system, which goes by the unwieldy name “Prisoner Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risk and Needs.” Luckily, the name collapses conveniently into the acronym “PATTERN.”

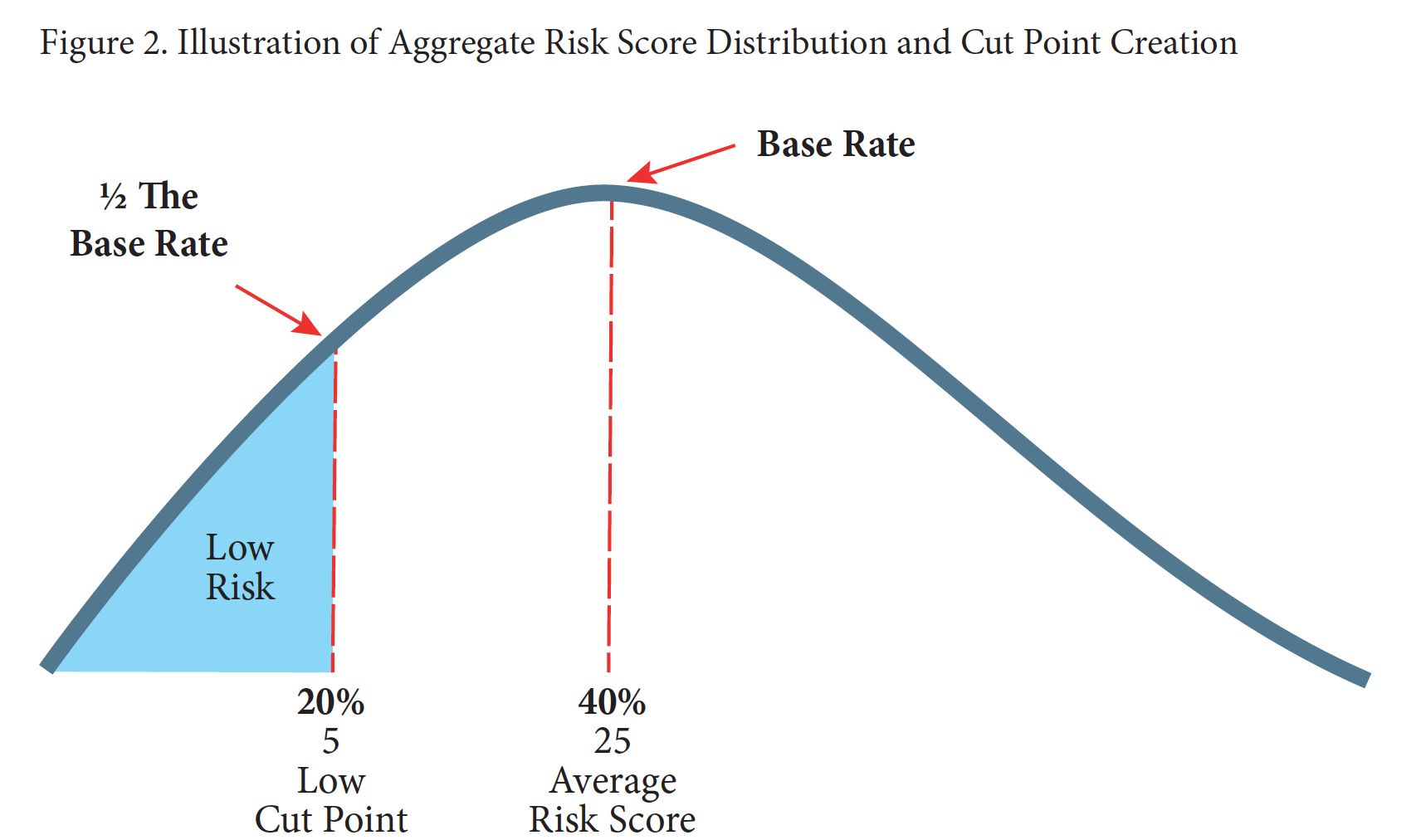

PATTERN will classify a BOP prisoner into one of four Risk Level Categories (“RLCs”) by scoring him or her in much the same way security and custody levels are calculated by the BOP. PATTERN does this by assigning points in 17 different categories. The highest possible score (like golf, no one wants a high score) is 100. The lowest score is -50.

This is roughly how it works: PATTERN has four different predictive models, 1) general recidivism for males; 2) general recidivism for females; 3) violent recidivism for males; and 4) violent recidivism for females. The Report noted that the base recidivism rate for all offenders is roughly 47% for general and 15% for violent recidivism.

The categories in which points are scored include (1) age of first conviction, (2) age at time of assignment, (3) prison infractions, (4) serious prison infractions, (5) number of programs completed, (6) number of tech or vocational courses completed, (7) UNICOR employment, (8) drug treatment, (9) drug education, (10) FRP status, (11) whether current offense is violent, (12) whether current offense is sex-related, (13) criminal history score, (14) history of violent offenses, (15) history of escapes, (16) voluntary surrender, and (17) education.

Generally, any score of -50 to +10 is a minimum recidivism risk, 11 to 33 is a low recidivism risk, 34 to 45 is a medium recidivism risk, and 46 or higher is a high risk. Its designers say “the PATTERN assessment instrument contains static risk factors as well as dynamic items that are associated with either an increase or a reduction in risk… PATTERN is a gender-specific assessment providing predictive models, or scales, developed and validated for males and females separately. These efforts make the tool more gender responsive, as prior findings have indicated the importance of gender-specific modeling.”

This means that as an inmate goes without getting disciplinary reports for infractions of prison rules, completes programs, keeps up with payment of fines and restitution, takes drug classes and gets older, his or her RLC category should fall. Even high and medium RLCs can earn credit for taking programs at the rate of 10 days per month, but once the RLC falls to low, that rate increases to 15 days per month.

So what BOP programs will build earned time credit? No one has said yet, but the PATTERN report offers clues. The PATTERN categories suggest that UNICOR employment, drug classes, GED and vocational programs ought to count, given PATTERN’s emphasis on importance of completion of those courses in the point system.

So what BOP programs will build earned time credit? No one has said yet, but the PATTERN report offers clues. The PATTERN categories suggest that UNICOR employment, drug classes, GED and vocational programs ought to count, given PATTERN’s emphasis on importance of completion of those courses in the point system.

PATTERN is not yet a done deal. What happens next is a 90-day public comment period on PATTERN rules. Final rules will issue by Thanksgiving, with BOP staff being trained in applying PATTERN. Do not expect any PATTERN assessment to be done for real until Martin Luther King Day.

Dept. of Justice, Department of Justice Announces the Release of 3,100 Inmates Under First Step Act, Publishes Risk And Needs Assessment System (July 19)

Wall Street Journal, Justice Department Set to Free 3,000 Prisoners as Criminal-Justice Overhaul Takes Hold (July 19)

Bureau of Prisons, Population Statistics (July 18)

Mother Jones, Congress Helped Thousands of People Get Out of Prison Early. But Many of Them Will Probably Be Deported Right Away (July 19)

USA Today, Federal government releases more than 2,200 people from prison as First Step Act kicks in (July 19)

Dept. of Justice, The First Step Act of 2018: Risk and Needs Assessment System (July 19, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root