We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SUPREME COURT BROADENS ACCA BURGLARY IN EARLY LUMP-OF-COAL DECISION

The Supreme Court yesterday issued an unexpectedly-early decision in United States v. Stitt, delivering a lump of coal to the stockings of people still hoping to to convince a court that their state burglary prior conviction should not count as a “prior” under the Armed Career Criminal Act. In a unanimous decision, the Court held in a Justice Breyer opinion that burglary of a structure or vehicle that has been adapted or is customarily used for overnight accommodation counts as a “generic burglary” in the ACCA’s “enumerated offenses” clause.

The Supreme Court yesterday issued an unexpectedly-early decision in United States v. Stitt, delivering a lump of coal to the stockings of people still hoping to to convince a court that their state burglary prior conviction should not count as a “prior” under the Armed Career Criminal Act. In a unanimous decision, the Court held in a Justice Breyer opinion that burglary of a structure or vehicle that has been adapted or is customarily used for overnight accommodation counts as a “generic burglary” in the ACCA’s “enumerated offenses” clause.

First, a review: Under the ACCA, a defendant convicted of being a felon in possession of a firearm under 18 USC 922(g)(1) receives an enhanced sentence. The basic 922(g)(1) conviction carries a zero to ten-year sentence. But if the ACCA applies, the sentence starts at 15 years and goes to a maximum of life.

A defendant qualifies for an ACCA sentence if he or she has three prior convictions for a serious drug offense or a crime of violence. The Stitt opinion concerned the ACCA’s crime-of-violence definition. A crime of violence is either (1) one of four listed crimes, burglary, arson, extortion or use of explosives, or (2) a crime which requires the use of force or threat of force against another. The first clause is known as the “enumerated offense” clause, which the second is called the “elements clause.”

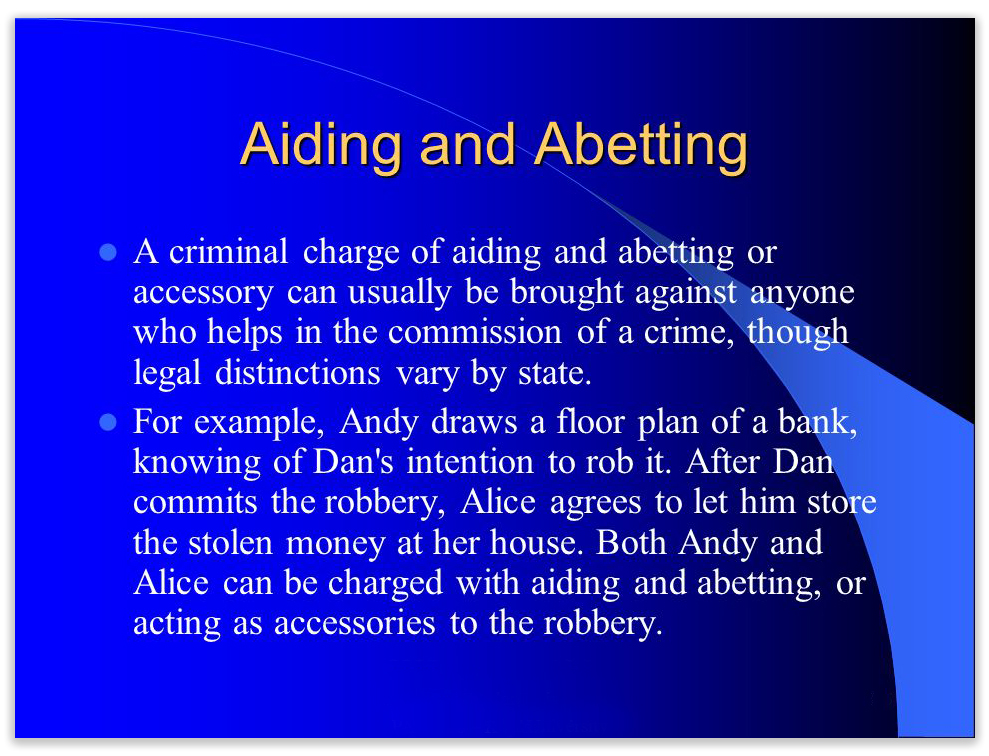

In deciding whether an offense qualifies as one of the enumerated offenses – burglary, extortion, arson or use of explosives – under the “violent felony” definition in the ACCA, the “categorical approach” first adopted in the 1990 decision Taylor v. United States requires courts to evaluate a prior conviction by reference to the elements of the offense instead of the defendant’s actual conduct. A prior state burglary conviction does not qualify as a generic burglary under the ACCA where the elements of the offense are “broader than those of generic burglary,” as explained in Mathis v. United States.

In deciding whether an offense qualifies as one of the enumerated offenses – burglary, extortion, arson or use of explosives – under the “violent felony” definition in the ACCA, the “categorical approach” first adopted in the 1990 decision Taylor v. United States requires courts to evaluate a prior conviction by reference to the elements of the offense instead of the defendant’s actual conduct. A prior state burglary conviction does not qualify as a generic burglary under the ACCA where the elements of the offense are “broader than those of generic burglary,” as explained in Mathis v. United States.

The Supreme Court has defined the elements of a generic burglary as “an unlawful or unprivileged entry into, or remaining in, a building or other structure, with intent to commit a crime. Under that definition, breaking into a car, a boat, an RV or even a mobile home often was not considered a burglary because it was not a “building or other structure.”

Yesterday’s decision changed all of that. In a consolidated case covering two defendants from two separate states, Arkansas and Tennessee, the Supreme Court expanded that previous definition, saying in effect that burglarizing anywhere that is used for overnight lodging falls within the ACCA’s generic burglary definition. The Court said Congress intended that the burglary definition reflect “the generic sense” in which the term ‘burglary’ was used in the criminal codes of most States when the ACCA was passed.

At that time, a majority of state burglary statutes covered vehicles adapted or customarily used for lodging. Also, Congress viewed burglary as an inherently dangerous crime that “creates the possibility of a violent confrontation” between the burglar and an occupant. An offender who breaks into a mobile home, an RV, a tent, or another structure or vehicle “adapted or customarily used for lodging creates a similar or greater risk of violent confrontation.”

At that time, a majority of state burglary statutes covered vehicles adapted or customarily used for lodging. Also, Congress viewed burglary as an inherently dangerous crime that “creates the possibility of a violent confrontation” between the burglar and an occupant. An offender who breaks into a mobile home, an RV, a tent, or another structure or vehicle “adapted or customarily used for lodging creates a similar or greater risk of violent confrontation.”

The Court said it did not matter if the vehicle or structure was only used for lodging part of the time, meaning that conceivably, breaking into new RVs on the dealer’s lot would still count toward an ACCA sentence.

One of the two defendants, Jason Sims complained that Arkansas’ statute remained too broad, because it also covers burglary of “a vehicle… [w]here any person lives.” He said since homeless people sometimes sleep in cars, this means that breaking into any car would fall under the ACCA definition. The Supreme Court said the question of whether the statute would be applied that way needed to be decided by a lower court, and remanded Jason’s case to a lower court to decide the merits of the claim.

United States v. Stitt, Case No. 17-765 (Supreme Court, Dec. 10, 2018)

United States v. Sims, Case No. 17-765 (Supreme Court, Dec. 10, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root

The statutes require that a defendant cause physical harm to the victim, but Ohio law defines “physical harm” to include mental harm. Several Ohio cases have convicted where defendants merely failed to prevent their kids from suffering mental trauma. For that reason, the 6th said, the statutes are overbroad.

The statutes require that a defendant cause physical harm to the victim, but Ohio law defines “physical harm” to include mental harm. Several Ohio cases have convicted where defendants merely failed to prevent their kids from suffering mental trauma. For that reason, the 6th said, the statutes are overbroad.