We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

TWO CIRCUITS SHOW SOME COMPASSION

The 1st and 4th Circuits have both issued significant compassionate release decisions in the last two weeks.

The 1st and 4th Circuits have both issued significant compassionate release decisions in the last two weeks.

Under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1), a sentencing court can grant a sentence reduction – known colloquially if not quite precisely as “compassionate release” – to a federal prisoner if the court finds “extraordinary and compelling reasons” for a sentence reduction, the reduction is consistent with Sentencing Commission policies, and that release would be consistent with the sentencing factors listed in 18 USC § 3553(a). Since passage of the First Step Act in 2018, a prisoner may bring a motion for compassionate release himself or herself.

What constitute “extraordinary and compelling reasons” are defined in the Guidelines at USSG § 1B1.13.

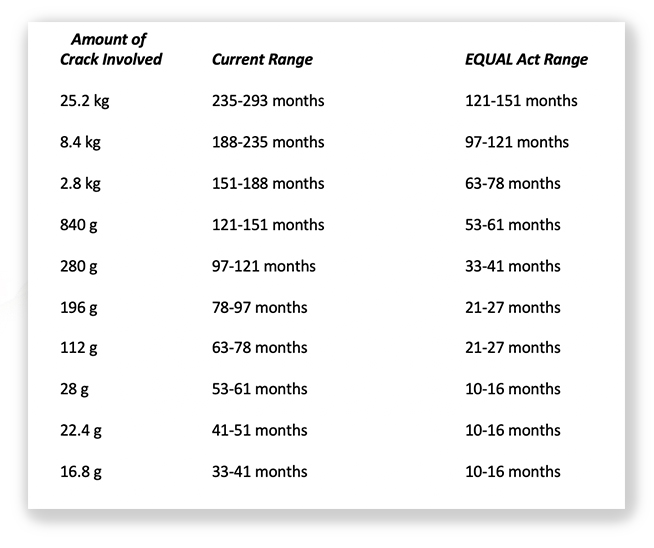

The 4th Circuit ruling first: Richard Smith has served about half of his 504-month crack cocaine conspiracy and stacked 18 USC § 924(c) sentences. He filed for compassionate release, citing his advanced age, poor health, rehabilitation efforts, and the disparity between his current sentence and the one he would receive for the same conduct if sentenced today.

The district court found that there were “extraordinary and compelling reasons” to grant the compassionate release motion, but in weighing the 18 USC § 3553 factors, the court concluded that “[r]eleasing Smith would not reflect the seriousness of the offense conduct, promote respect for the law, provide just punishment for the offense, or deter criminal conduct.” The district court noted Dick’s prior state convictions for drugs and domestic battery and complained that the estimated amount of crack cocaine used by the original sentencing judge “was low.” The judge refused to consider the non-retroactive First Step Act amendments to 18 USC § 924(c) and for good measure, said that even if he did consider the changes, “they would not overcome the finding that the § 3553(a) factors weigh against a sentence reduction.”

Last week, the 4th Circuit reversed the district court and remanded with instructions to let Dick go home. First, it held that the sentence disparity created by the First Step Act’s elimination of “stacked” mandatory minimums under § 924(c) can constitute an “extraordinary and compelling reason” under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A)(i) (thus suggesting the Sentencing Commission’s compassionate release guideline 1B1.13(b)(6) is lawful). The issue of whether (b)(6) – which authorizes a district court to consider nonretroactive changes in the law as part of an “extraordinary and compelling reason” analysis – exceeds Sentencing Commission authority is currently before the Supreme Court in Rutherford v. United States and will be decided next spring.

Second (and more significant for compassionate release movants), the Circuit concluded that the district court’s rote recitation of § 3553 factors “fail[ed] to recognize that the relevant § 3553(a) factors clearly favor release.” Dick was no recidivism risk, the 4th said, no matter what his criminal history in the last century might have been, due to “his advanced age and serious medical conditions. Smith was 66 years old at the time he filed his renewed motion for compassionate release. He is 71 years old today… Moreover, Smith suffers from black lung disease, an irreversible respiratory impairment resulting from his years as a coal miner. Smith has also been diagnosed with COPD, emphysema, pre-diabetes, a liver cyst, and a heart rhythm disorder. He is totally disabled and a portion of his right lung has been removed.”

Dick only had two minor disciplinary infractions in 20 years, completed dozens of vocational classes and participated in drug treatment programs. He worked his way down from high security to low. “This is not the picture of an unremorseful defendant bent on causing future harm even if he was physically able,” the 4th said.

Dick only had two minor disciplinary infractions in 20 years, completed dozens of vocational classes and participated in drug treatment programs. He worked his way down from high security to low. “This is not the picture of an unremorseful defendant bent on causing future harm even if he was physically able,” the 4th said.

The Circuit noted that “the district court determined, without elaboration, that a reduced sentence would fail to ‘deter criminal conduct.’ But this ignores that, by the time of his release, Smith will have already served nearly 25 years of his 42-year sentence. The prospect of 25 years of prison time serves as a powerful deterrent against the conduct—which was undoubtedly serious—for which Smith was convicted and sentenced.”

Meanwhile, Edison Burgos filed for compassionate release on the grounds that the BOP was failing to treat his hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. The district court held that Eddie was getting “adequate medical, dental and psychological care” and denied his motion. Two weeks ago, the 1st Circuit reversed, holding that the district court had “overlooked the undisputed evidence demonstrating that, almost one year after Ed’s sleep apnea diagnosis and despite his ongoing severe hypertension, the BOP had yet to provide him with the established treatment for sleep apnea.”

The BOP argued that the fact that Ed’s medical records show that a “second sleep study was listed as an ‘urgent’ priority…” was “sufficient evidence that the BOP was adequately treating him for sleep apnea.” The 1st ripped that fig leaf away:

Even if we overlook that the “urgent” sleep study had yet to be conducted as of Dr. Venuto’s second letter to the court, however, a sleep study is a diagnostic tool: The only treatment for sleep apnea discussed in Burgos-Montes’s medical records is a CPAP machine… Indeed, as we have explained, in April 2022, an outside cardiologist recommended that Burgos-Montes receive a CPAP machine “ASAP” to treat his sleep apnea, without suggesting that additional diagnostic testing was needed. And Dr. Venuto acknowledged that as of July 2022, Burgos-Montes had still not received a CPAP machine.

The Circuit ruled that “the record is clear that nearly a year after Burgos-Montes received a sleep apnea diagnosis, months after a consulting cardiologist recommended that he receive a CPAP machine “ASAP,” and even after his transfer to a higher-level care facility, the BOP had yet to provide Burgos-Montes with a CPAP machine or any other sleep apnea treatment. And there is no dispute that untreated sleep apnea for a patient like Burgos-Montes, who also suffers from severe hypertension, could amount to an ‘extraordinary and compelling’ reason to grant compassionate release.”

The Circuit ruled that “the record is clear that nearly a year after Burgos-Montes received a sleep apnea diagnosis, months after a consulting cardiologist recommended that he receive a CPAP machine “ASAP,” and even after his transfer to a higher-level care facility, the BOP had yet to provide Burgos-Montes with a CPAP machine or any other sleep apnea treatment. And there is no dispute that untreated sleep apnea for a patient like Burgos-Montes, who also suffers from severe hypertension, could amount to an ‘extraordinary and compelling’ reason to grant compassionate release.”

United States v. Smith, Case No. 24-6726, 2025 U.S.App. LEXIS 16565 (4th Cir. July 7, 2025)

Rutherford v. United States, Case No. 24-820 (cert. granted June 6, 2025)

United States v. Burgos-Montes, Case No. 22-1714, 2025 U.S.App. LEXIS 16048 (1st Cir. June 30, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root