We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

3RD CIRCUIT ISSUES REMARKABLE INEFFECTIVE-ASSISTANCE DECISION

When prisoners file post-conviction motions, such as the motion under 28 USC § 2255, they are not entitled to appointed counsel under the Sixth Amendment. However, if their claims seem on their face to be sufficiently meritorious, the courts often appoint lawyers to help them in an evidentiary hearing or on appeal.

How the courts select counsel to appoint varies from district to district and circuit to circuit. What does not vary is the relatively small amount of compensation paid for the lawyers’ work.

How the courts select counsel to appoint varies from district to district and circuit to circuit. What does not vary is the relatively small amount of compensation paid for the lawyers’ work.

This is where the appointed counsel lottery comes in.

Usually, a solo practitioner or small firm is appointed, and the amount of time those appointed attorneys can devote is limited by the pedestrian need to make a living. If the hours you bill are what will put food on next month’s table, you are motivated to spend no more time on the appointment than fees available for compensation. It’s a fact of life.

A few times in my career, I have seen the occasional prisoner have appointed to him or her a lawyer at one of the “big law” firms – law partnerships with hundreds of lawyers and a culture of providing every client with a quarter-million dollar defense, regardless of whether the client is Megacorp International or Peter Pauper. I recall one defendant in Indiana calling me to report the court had appointed some lawyer from Washington, D.C. to represent him, at a firm named Jones Day or something like that.

“My friend,” I said, “you just won the lottery.”

(For the uninitiated, I note that Jones, Day, with over 2,500 lawyers and offices around the world, is one of the top grossing firms on the planet. Wikipedia describes it as “one of the most elite law firms in the world”).

And what a difference unlimited resources made for the Indiana defendant.

Just as big a win is when a top-ranked law school has a driven law prof and a gaggle of smart law students working in a practicum. Law students are allowed to provide representation in some cases, under guidance of a licensed attorney-professor. I know a vigorous pro se inmate with a complex legal question to whom a Georgetown University professor and her students were assigned by the D.C. Circuit. The representation he got could not have been purchased for $300,000.

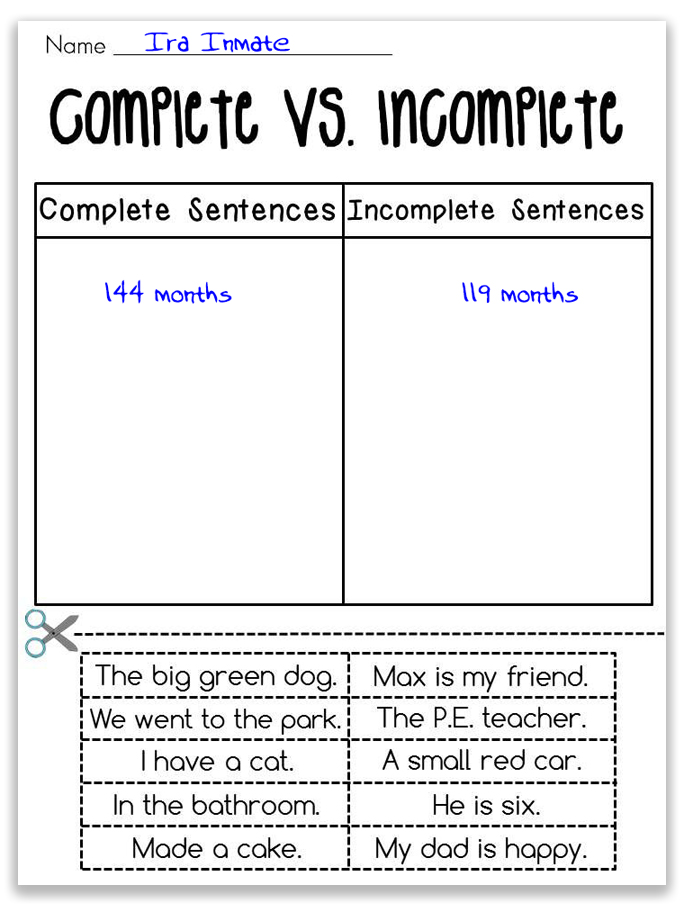

Today, we consider lottery winner Peter Sepling. Pete pled guilty to importing gamma butyrolactone (GBL), a schedule I analogue drug. His lawyer cut a good deal, one that would let him get sentenced without application of a Guidelines career offender enhancement.

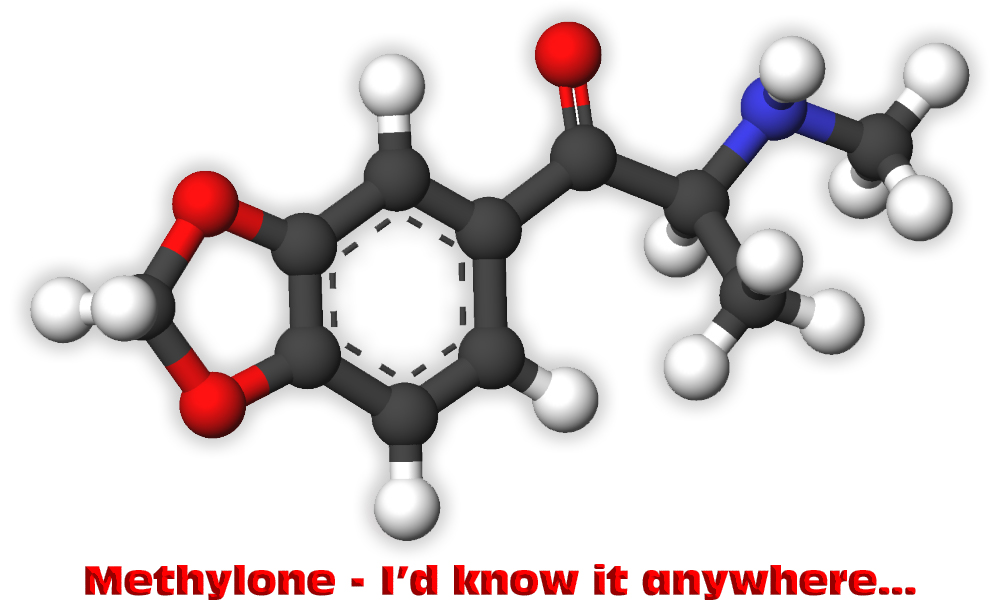

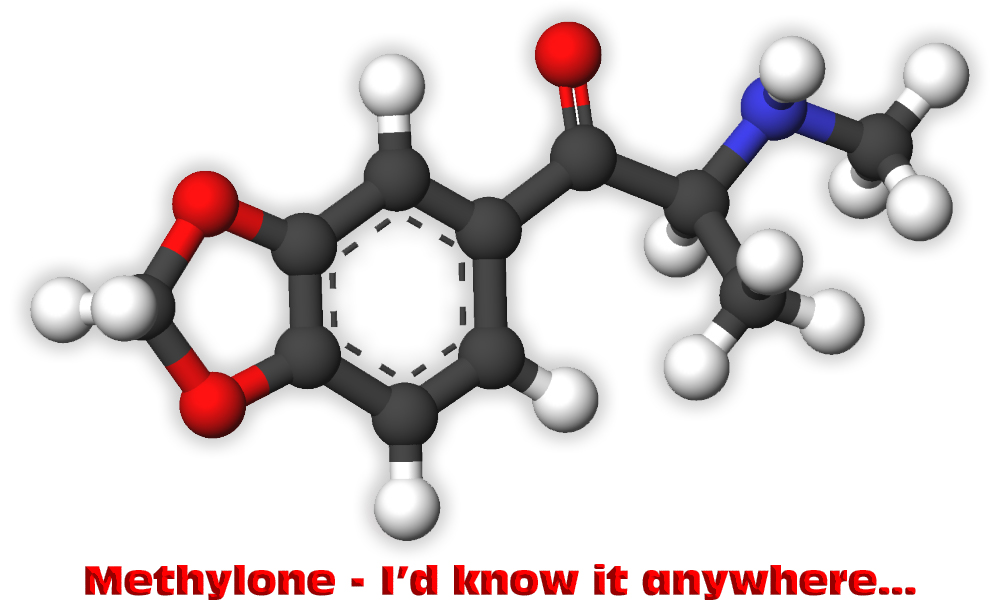

But while on bond, Pete got busted for conspiracy to import methylone, another Schedule I drug.

Pete cut a deal on the new charge where he would not be prosecuted for the methylone, but instead, it would be factored into the sentence he would get in the GBL case. This is where the fun started.

Pete cut a deal on the new charge where he would not be prosecuted for the methylone, but instead, it would be factored into the sentence he would get in the GBL case. This is where the fun started.

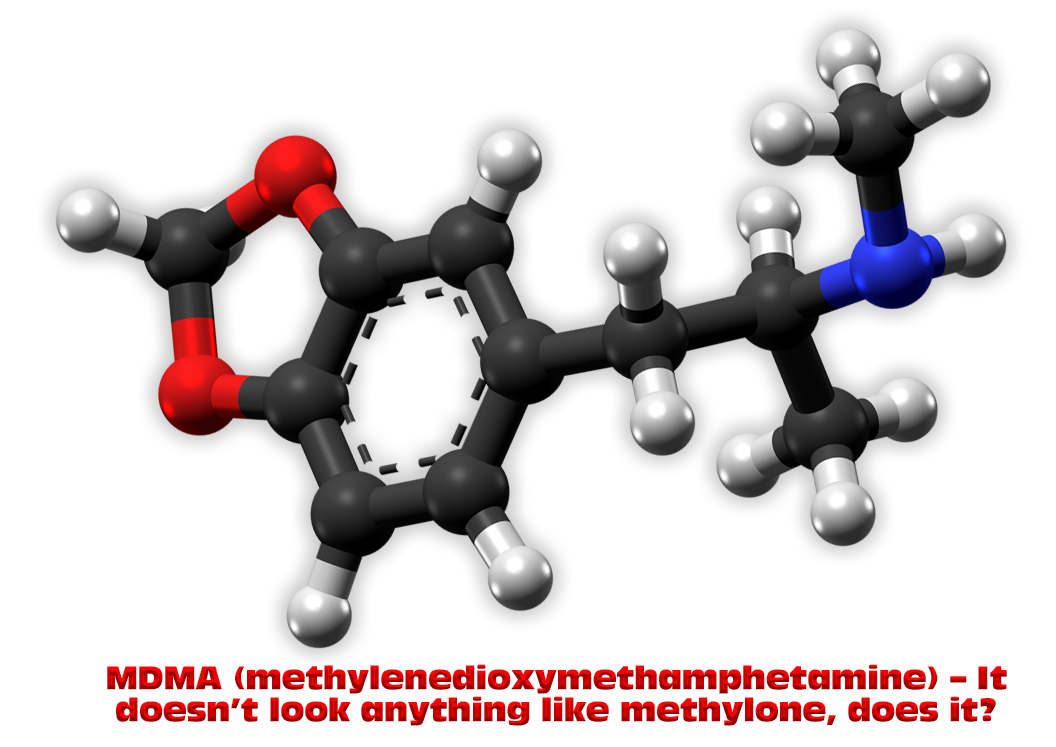

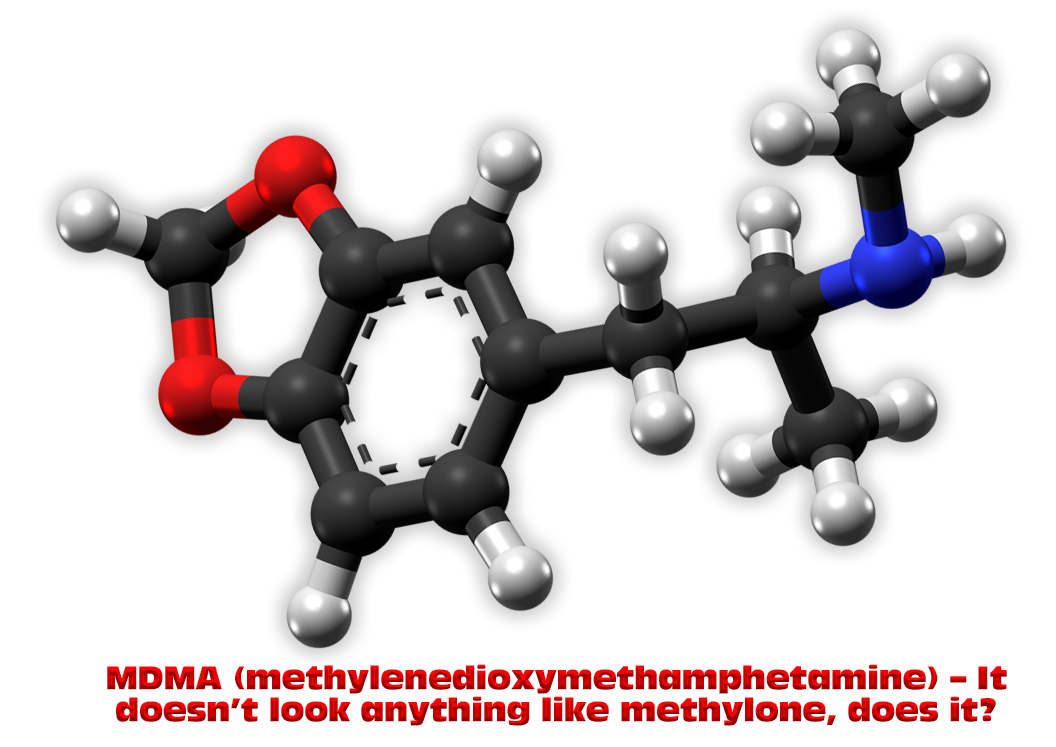

The Guidelines do not contain any offense level for methylone. Pete’s presentence report compared methylone to methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), commonly known as ecstasy. The Guidelines holds ecstasy to be pretty bad stuff, equating a unit of that drug to 500 units of marijuana. Consequently, the District Court started its sentencing determination using this 500:1 ratio. In Pete’s case, this converted to 5,000 kilos of pot. The net result was that his Guidelines sentencing range of 27-33 months soared to 188-235 months.

Pete’s lawyer did not object to the methylone-ecstasy comparison, or to the sentencing range. Nor did he file a sentencing memorandum. At sentencing, defense counsel admitted to the court that he had “never heard of methylone… until Sepling got rearrested,” and that he had attempted to learn about the drug from the government. Counsel further explained that the government “tried to educate me… as Mr. Sepling tried to educate me. My understanding of the drug, which is very little, is that drug is – Spellman will explain to the Court – it’s like a watered down ecstasy.”

For its part, the Government also knew next to nothing about methylone.

At his attorney’s request, Pete told the Court methylone is “like ecstasy. If ecstasy is a ten… this stuff is six and lasts about an hour and a half.”

The Court admitted it did not know anything about methylone, either, but observed that “in any event, it’s a controlled substance. It’s mind altering. It affects people’s behavior. It’s not a good thing. So I will consider that.” The Court varied downward from the Guidelines, but still gave Pete 102 months, telling him “you’ve committed a serious crime here, and it’s — in particular the methylone and that you put people in harm’s way.”

The Court admitted it did not know anything about methylone, either, but observed that “in any event, it’s a controlled substance. It’s mind altering. It affects people’s behavior. It’s not a good thing. So I will consider that.” The Court varied downward from the Guidelines, but still gave Pete 102 months, telling him “you’ve committed a serious crime here, and it’s — in particular the methylone and that you put people in harm’s way.”

Pete filed a post-conviction motion under 28 USC § 2255, complaining that his lawyer failed to investigate methylone, and if he had, he would have found that the comparison to ecstasy was way overblown. The district court turned him down, finding that counsel’s performance was not ineffective because, “although sentencing counsel acknowledged that he knew little about methylone, he appropriately likened the drug to a ‘watered down ecstasy’” and “counsel’s characterization of the drug was consistent with Petitioner’s statements at sentencing.”

Then, Pete’s fortunes changed. On appeal the 3rd Circuit assigned a Duke University law school professor and three Duke law students working in the school’s appellate advocacy clinic to represent Pete. The Blue Devil counselors-in-training pulled out all the stops. Last week, they bulldozed the 3rd Circuit – in a remarkable decision – into reversing the district court, finding that Pete’s lawyer was ineffective, and holding that Pete was prejudiced by it.

Then, Pete’s fortunes changed. On appeal the 3rd Circuit assigned a Duke University law school professor and three Duke law students working in the school’s appellate advocacy clinic to represent Pete. The Blue Devil counselors-in-training pulled out all the stops. Last week, they bulldozed the 3rd Circuit – in a remarkable decision – into reversing the district court, finding that Pete’s lawyer was ineffective, and holding that Pete was prejudiced by it.

The Circuit initially noted that Pete’s lawyer made the first question – whether his representation fell below the standards required of attorneys – an easy one to answer. At sentencing, the attorney admitted he knew nothing about methylone, and he made it clear that he had done nothing to educate himself, despite having a clear duty to do so. The decision cites several scientific studies and court decisions that were available to him, all of which found that methylone is much less serious that ecstasy. The 3rd said that “properly prepared counsel could have made a strong argument, grounded in readily available research, that methylone is significantly less serious than MDMA.”

In other words, the 3rd Circuit said that Pete’s lawyer was ineffective for not arguing that the Guidelines’ 500:1 ratio was flawed, and should be ignored by the sentencing court. Ineffectiveness for failing to attack the Guidelines for being wrong is a holding without precedent.

The district court denied Pete’s § 2255 motion in part because defense counsel’s description of methylone was good enough, and that Pete himself testified as to its effects as sentencing. The 3rd Circuit blew that justification apart:

Rather than doing any research into the pharmacological effect of methylone in order to competently represent his client and inform the District Court’s application of the Guidelines table, Sentencing Counsel relied upon his client to explain the effects of methylone. Sentencing Counsel thus “decided to outsource to Sepling any discussion of methylone at the hearing.”

Still, lawyer ineffectiveness is only one-half of the equation. If a lawyer screws the pooch, but the defendant ends up being none the worse for the blunder, there is (in the words of Strickland v. Washington, the Holy Grail of ineffective assistance of counsel) no prejudice.

After having read hundreds of 2255 decisions over the past 25 years, I was sure what was coming. Pete was sentenced far below his Guidelines range. Normally, a court would hold that because Pete got a downward variance sentence well under his guidelines, he could not possibly have been prejudiced by his lawyer’s failures.

After having read hundreds of 2255 decisions over the past 25 years, I was sure what was coming. Pete was sentenced far below his Guidelines range. Normally, a court would hold that because Pete got a downward variance sentence well under his guidelines, he could not possibly have been prejudiced by his lawyer’s failures.

But instead, the 3rd Circuit quite properly said the below-guidelines sentence was irrelevant to whether Pete was prejudiced:

A significant variance from an arguably high and inaccurate guideline sentence is not a gift. The District Court expressed a desire to base Sepling’s sentence on the seriousness of distributing methylone. It is impossible to review the transcript of the sentencing proceeding without concluding that the District Court did not have sufficient information to assess the actual seriousness of methylone. We therefore cannot dismiss the very real possibility that the court may have been amenable to a further downward variance based upon evidence specific to methylone’s reduced effect as compared to MDMA… Because Sentencing Counsel’s dereliction put the District Court in a position where it was literally ‘flying blind’ at sentencing, there was no way for a district court to know if the sentence imposed was the least serious penalty consistent with the Court’s objective in imposing the sentence.

This is an astounding case. I salute Duke Law (and sorry about the Stephen F. Austin thing).

United States v. Sepling, 2019 U.S. App. LEXIS 35706 (3rd Cir. Nov. 29, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root

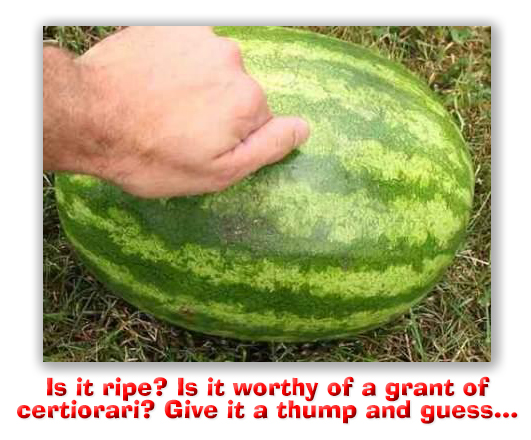

The Supreme Court last week refused to hear a challenge to 28 USC § 2244, the statute governing when prisoners should be permitted to file a second or successive habeas corpus motion under 28 USC § 2254 (for state prisoners) or 28 USC § 2255 (for federal prisoners). The denial is noteworthy for Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s published statement that the high court should settle a circuit split on the issue the next time a similar case comes before it.

The Supreme Court last week refused to hear a challenge to 28 USC § 2244, the statute governing when prisoners should be permitted to file a second or successive habeas corpus motion under 28 USC § 2254 (for state prisoners) or 28 USC § 2255 (for federal prisoners). The denial is noteworthy for Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s published statement that the high court should settle a circuit split on the issue the next time a similar case comes before it. An influential Washington, D.C., law firm took up the battle for Ed, arguing in a petition for writ of cert that the 6th Circuit’s published contrary ruling created a circuit split that called for resolution. He faced no pushback: the government had already filed a brief in the 6th Circuit saying it agreed that 28 USC § 2244 does not apply to § 2255 motions.

An influential Washington, D.C., law firm took up the battle for Ed, arguing in a petition for writ of cert that the 6th Circuit’s published contrary ruling created a circuit split that called for resolution. He faced no pushback: the government had already filed a brief in the 6th Circuit saying it agreed that 28 USC § 2244 does not apply to § 2255 motions.