We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

DARKEST HOUR FOR HOBBS ACT JUST BEFORE DAWN?

In the wake of last summer’s United States v. Davis Supreme Court decision, a number of federal defendants began asking whether attempting to commit or aiding and abetting a Hobbs Act robbery (18 USC § 1951) can be considered a “crime of violence” that will support an 18 USC § 924(c) conviction and mandatory add-on sentence for possession or use of a gun in the underlying offense. In other words, a crime that any reasonable person might think is violent may not be quite violent enough.

In the wake of last summer’s United States v. Davis Supreme Court decision, a number of federal defendants began asking whether attempting to commit or aiding and abetting a Hobbs Act robbery (18 USC § 1951) can be considered a “crime of violence” that will support an 18 USC § 924(c) conviction and mandatory add-on sentence for possession or use of a gun in the underlying offense. In other words, a crime that any reasonable person might think is violent may not be quite violent enough.

A primer: Under 18 USC § 924(c), anyone who commits a drug trafficking offense or a crime of violence while possessing a firearm is sentenced for the underlying crime, and then hit with a mandatory additional sentence of at least five year and up to life in prison. The minimum sentences increase if the defendant brandished the gun (minimum additional seven-year sentence) or actually fired it (minimum additional seven-year sentence). The hot arguments over the past decade have been what makes an underlying crime a “crime of violence,” with Davis being only the latest case to take up the question.

And yesterday, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Shular v. United States, which could bring the same kind of scrutiny to what constitutes a drug offense that Davis and its antecedents brought to crimes of violence.

Enough background… now for the news. Last week was not especially helpful to defendants hoping that Hobbs Act robbery might be found to be other than a crime of violence. Parts were nasty and brutish. But, mercifully, those may also be short.

First, the Supreme Court denied certiorari on a closely-watched petition filed in Mojica v. United States, which asked indirectly whether a § 924(c) conviction could be based on a conviction for aiding and abetting a Hobbs Act robbery. Mojica argued that aiding or abetting a Hobbs Act robbery was not a “crime of violence” after Davis, because viewed categorically, a Hobbs Act robbery could be committed without using or threatening force. Although there were early signs of Supreme Court interest in the case, brought by talented post-conviction attorney Brandon Sample, certiorari was denied on Jan. 10.

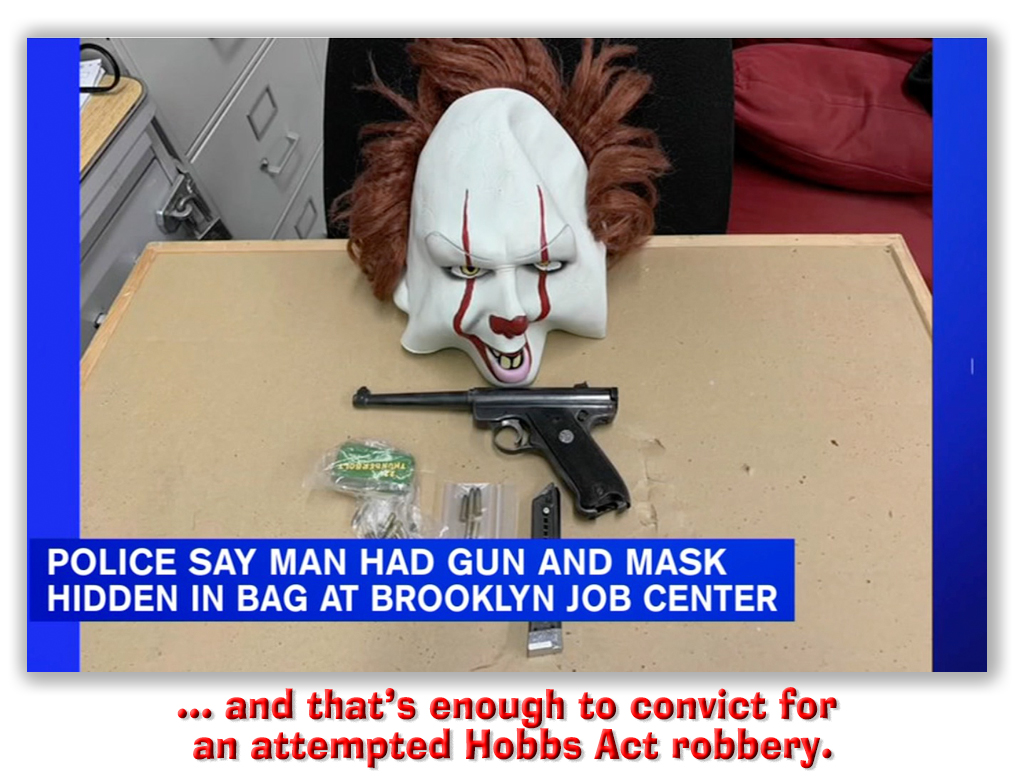

Meanwhile, the 7th Circuit rejected claims that an attempt to commit a Hobbs Act robbery is not a crime of violence under the elements test of § 924. Because a Hobbs Act robbery qualifies as a crime of violence, the Circuit said, and because a jury has to find the defendant intended to commit the robbery in order to convict him for attempt, attempted Hobbs Act robbery is a “valid predicate offense” for 924(c).

Meanwhile, the 7th Circuit rejected claims that an attempt to commit a Hobbs Act robbery is not a crime of violence under the elements test of § 924. Because a Hobbs Act robbery qualifies as a crime of violence, the Circuit said, and because a jury has to find the defendant intended to commit the robbery in order to convict him for attempt, attempted Hobbs Act robbery is a “valid predicate offense” for 924(c).

One ray of sunshine fell in the 9th Circuit, which in an unpublished opinion said, “We accept the government’s concession that conspiracy to commit Hobbs Act robbery is not a crime of violence under 18 USC 924(c)(3) in light of the Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. v Davis… Therefore, we vacate defendants’ convictions for carrying and discharging a firearm in furtherance of a crime of violence.”

A second ray of light may have flickered the week before. An alert reader commended my attention to Judge Sterling Johnson’s fascinating holding in United States v. Tucker, handed down January 8th. A defendant was charged with conspiracy to rob a Brooklyn gas station and an attempt to rob the station, both Hobbs Act offenses. (How something so criminally prosaic as robbing a gas station became a federal offense is a question I’ll leave for another day.) He was also charged with two § 924(c) offenses, one for possessing a gun during the conspiracy to rob and another for possessing a gun during the attempt to rob. If convicted of the 924(c) offenses, defendant Tambhia Tucker would have had a minimum of ten extra years added to whatever he might get for the conspiracy and the attempted robbery.

A second ray of light may have flickered the week before. An alert reader commended my attention to Judge Sterling Johnson’s fascinating holding in United States v. Tucker, handed down January 8th. A defendant was charged with conspiracy to rob a Brooklyn gas station and an attempt to rob the station, both Hobbs Act offenses. (How something so criminally prosaic as robbing a gas station became a federal offense is a question I’ll leave for another day.) He was also charged with two § 924(c) offenses, one for possessing a gun during the conspiracy to rob and another for possessing a gun during the attempt to rob. If convicted of the 924(c) offenses, defendant Tambhia Tucker would have had a minimum of ten extra years added to whatever he might get for the conspiracy and the attempted robbery.

Tambhia filed a pretrial motion to dismiss both 924(c) counts, arguing that after Davis, neither a conspiracy nor an attempt could support a 924(c) conviction. Judge Johnson agreed, holding that Davis made short work of the 924(c) connected to the conspiracy. As for the attempt, the Judge noted that in the 2nd Circuit, previous holdings have established that conducting surveillance of an intended robbery target, or even just obtaining a getaway car for use in a robbery, was enough to convict for attempted Hobbs Act robbery. The Judge concluded that

it is incorrect to say that a person necessarily attempts to use physical force within the meaning of 924(c)’s elements clause just because he attempts a crime that, if completed would be violent… The defense reasonably interprets “surveillance” as the “minimum criminal conduct,” necessary to convict for attempted Hobbs Act robbery. Thus, the question becomes whether a person conducting surveillance of a target with the intent to commit robbery necessarily uses, attempts to use, or threatens the use of force… A person may engage in an overt act — in the case of robbery, for example, overt acts might include renting a getaway van, parking the van a block from the bank, and approaching the bank’s door before being thwarted — without having used, attempted to use, or threatened to use force. Would this would-be robber have intended to use, attempt to use, or threaten to use force? Sure. Would he necessarily have attempted to use force? No.

As Tucker has pointed out, in the Second Circuit, even less severe conduct, such as “reconnoitering” a target location or possessing “paraphernalia to be employed in the commission of the crime,” can constitute a substantial step and lead to an attempt conviction… Accordingly… this court finds that given the broad spectrum of attempt liability, the elements of attempt to commit robbery could clearly be met without any use, attempted use, or threatened use of violence.

Judge Johnson dismissed both 924(c) counts.

This will hardly be the last word on an attempted robbery offense, but it certainly advances the debate.

This will hardly be the last word on an attempted robbery offense, but it certainly advances the debate.

Mojica v. United States, Case No. 19-35 (cert. denied Jan. 13, 2020)

United States v. Ingram, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 1531 (7th Cir. Jan 17, 2020)

United States v. Soto-Barraza, Case No. 15-10856 (9th Cir. Jan 17, 2020) (unpublished)

United States v. Tucker, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3035 (E.D.N.Y. Jan. 8, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root

In 2001, Brandon Gravatt was convicted of conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute 5 kilograms or more of powder cocaine and 50 grams or more of crack cocaine (21 USC § 846). He pled guilty to the dual-object drug conspiracy charge, facing sentences of 10 years-to-life for the coke and 10-to-life for the crack. The court sentenced him to just short of 22 years.

In 2001, Brandon Gravatt was convicted of conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute 5 kilograms or more of powder cocaine and 50 grams or more of crack cocaine (21 USC § 846). He pled guilty to the dual-object drug conspiracy charge, facing sentences of 10 years-to-life for the coke and 10-to-life for the crack. The court sentenced him to just short of 22 years. Joining the 6th and 9th Circuits, the 11th held that because the Guidelines definition of robbery and extortion only extends to physical force against persons, while under Hobbs Act robbery and extortion, the force can be employed or threatened against property as well, the Hobbs Act (18 USC § 1951) is broader than the Guidelines definition, and thus cannot be a crime of violence for career offender purposes.

Joining the 6th and 9th Circuits, the 11th held that because the Guidelines definition of robbery and extortion only extends to physical force against persons, while under Hobbs Act robbery and extortion, the force can be employed or threatened against property as well, the Hobbs Act (18 USC § 1951) is broader than the Guidelines definition, and thus cannot be a crime of violence for career offender purposes.