We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

Today, we have some leftovers for you, chiefly because we got so busy last week that we did not get caught up with posting before the weekend was upon us.

NUMBERS OF THE DAY

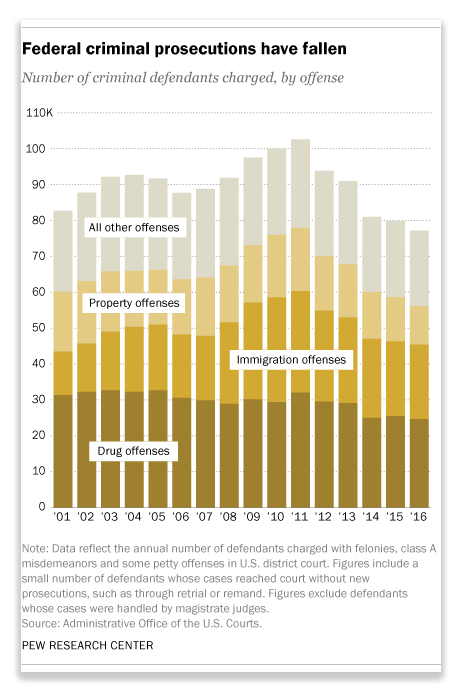

After peaking in 2011, the number of federal criminal prosecutions has declined each year since, is now at its lowest level in nearly 20 years.

A Pew Research Center analysis released last week reported that the 77,000 people charged in fiscal years 2016 was a 25% decline over five years before, when 103,000 defendants were charged.

A Pew Research Center analysis released last week reported that the 77,000 people charged in fiscal years 2016 was a 25% decline over five years before, when 103,000 defendants were charged.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions has indicated that the Justice Department will ramp up criminal prosecutions in the years ahead, leading some to suspect that the rate will climb again.

Pew Research Center, Federal criminal prosecutions fall to lowest level in nearly two decades (Mar. 28, 2017)

CASH TAKE OF THE DAY

Last summer, USA Today reported that the DEA relies on a network of travel-industry informants, from ticket sellers to back office IT people, to single out passengers for asset seizures. The paper reported that 85% of cash seizures occurred as a result of such interdiction operations at transportation facilities or highway stops.

Turns out there’s a good reason for that. In a report issued last week, the Dept. of Justice Inspector General found the DEA has seized more than $4 billion in cash since 2007, with 81% of those seizures – totaling $3.2 billion – were conducted without civil or criminal charges being brought against the owners of the cash, and without any judicial review of the seizure. And that total does not include the value of other seized assets like cars, homes, boats or electronics.

Turns out there’s a good reason for that. In a report issued last week, the Dept. of Justice Inspector General found the DEA has seized more than $4 billion in cash since 2007, with 81% of those seizures – totaling $3.2 billion – were conducted without civil or criminal charges being brought against the owners of the cash, and without any judicial review of the seizure. And that total does not include the value of other seized assets like cars, homes, boats or electronics.

The OIG report found the DEA could verify that only 44% of the seizures studied had been related to ongoing or new investigations or led to prosecutions. “When seizure and administrative forfeitures do not ultimately advance an investigation or prosecution,” the report said, “law enforcement creates the appearance, and risks the reality, that it is more interested in seizing and forfeiting cash than advancing an investigation or prosecution.”

In a written response to the Inspector General included in the report, the Justice Department’s Criminal Division disputed both the report’s findings and methodology. It maintains that civil asset forfeiture is “a critical tool to fight the current heroin and opioid epidemic that is raging in the United States.”

USA Today, DEA regularly mines Americans’ travel records to seize millions in cash (Aug. 10, 2016)

Office of Inspector General, DOJ, Review of the Department’s Oversight of Cash Seizure and Forfeiture Activities (Mar. 29, 2017)

Washington Post, Since 2007, the DEA has taken $3.2 billion in cash from people not charged with a crime (Mar. 29, 2017)

Reason, DEA Seized $4 Billion From People Since 2007. Most Were Never Charged with a Crime (Mar. 29, 2017)

THE FIRST STIRRINGS OF SENTENCE REFORM?

Jared Kushner, son-in-law and senior adviser to President Donald Trump, met last Thursday with Sens. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Richard Durbin (D-Illinois) on Capitol Hill last Thursday to discuss revival of the sentencing reform legislation that stalled at the end of the last session of Congress.

The story broke on the paragon of journalism excellence, Buzzfeed, leaving us to withhold noting it until some more acceptable journalistic sources picked up the story. It does, however, appear to be accurate.

Grassley, chairman of the judiciary committee, and Durbin, the Democratic whip, have said they want to bring back sentencing reform legislation in this Congress. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), a strong advocate for criminal justice reform, attended the meeting as well.

Grassley, chairman of the judiciary committee, and Durbin, the Democratic whip, have said they want to bring back sentencing reform legislation in this Congress. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), a strong advocate for criminal justice reform, attended the meeting as well.

Grassley said he will “know in three weeks” whether the White House is interested in the legislation. He told reporters, “We’re trying to reach some accommodation, if there needs to be any adjustment to the bill we had last year.”

A broad coalition — including the ACLU and the conservative Koch Industries — says the federal criminal justice system is broken. Grassley, Durbin and Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), sponsored the prior bill in the Senate. House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wisconsin, was a strong supporter of the effort.

US News, White House Adviser Kushner, Senator Talk Criminal Justice (Mar. 30, 2017)

Buzzfeed News, White House sends Jared Kushner to meet with top senators on improving the criminal justice system (Mar. 30, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root