We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

3RD CIRCUIT’S TROUBLING SUGGESTIONS ON 922(g)(1)

Following its en banc Range v Attorney General II decision– that the 18 USC 922(g)(1) felon-in-possession (F-I-P) statute violates the 2nd Amendment where it prohibits a person with a single disqualifying but nonviolent fraud conviction 25 years before from owning a gun – the 3d Circuit earlier this week remanded a similar case for the trial court to inquire into whether the petitioner had a history of dangerousness.

Restaurateur George Pitsilides’ hobby is high-stakes poker, an avocation that extended into sports betting and hosting illegal poker tournaments. He was convicted 25 years ago of placing sports bets with a Pennsylvania bookie – law-breaking that must seem quaint to anyone watching Eli and Peyton Manning on the Fanduel ad during the Superbowl – conduct that disqualifies him from gun possession under the F-I-P statute.

Restaurateur George Pitsilides’ hobby is high-stakes poker, an avocation that extended into sports betting and hosting illegal poker tournaments. He was convicted 25 years ago of placing sports bets with a Pennsylvania bookie – law-breaking that must seem quaint to anyone watching Eli and Peyton Manning on the Fanduel ad during the Superbowl – conduct that disqualifies him from gun possession under the F-I-P statute.

In 2019, he sued the government for the right to own a gun, arguing among other things that the F-I-P statute violated the 2nd Amendment as applied to his situation. While the case was on appeal, the Supreme Court handed down decisions in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen and United States v. Rahimi, cases “which effected a sea change in 2nd Amendment law,” as the 3rd Circuity put it, and required that a record be made of George’s “dangerousness.”

The Circuit held that while Rahimi and Range II “did not purport to comprehensively define the metes and bounds of justifiable burdens on the 2nd Amendment right, they do, at a minimum, show that disarmament is justified as long as a felon continues to “present a special danger of misusing firearms… in other words, when he would likely pose a physical danger to others if armed.” The appellate court observed that

The Circuit held that while Rahimi and Range II “did not purport to comprehensively define the metes and bounds of justifiable burdens on the 2nd Amendment right, they do, at a minimum, show that disarmament is justified as long as a felon continues to “present a special danger of misusing firearms… in other words, when he would likely pose a physical danger to others if armed.” The appellate court observed that

[a]s evidenced by our opinion in Range II, the determination that a felon does not currently present a special danger of misusing firearms may depend on more than just the nature of his prior felony…. [W]e agree with the 6th Circuit: Courts adjudicating as-applied challenges to 922(g)(1) must consider a convict’s entire criminal history and post-conviction conduct indicative of dangerousness, along with his predicate offense and the conduct giving rise to that conviction, to evaluate whether he meets the threshold for continued disarmament. As Range II illustrated, consideration of intervening conduct plays a crucial role in determining whether application of 922(g)(1) is constitutional under the 2nd Amendment… Indeed, such conduct may be highly probative of whether an individual likely poses an increased risk of “physical danger to others” if armed.

The Circuit ruled that “while bookmaking and pool selling offenses may not involve inherently violent conduct, they may nonetheless, depending on the context and circumstances, involve conduct that endangers the physical safety of others. That assessment necessarily requires individualized factual findings.”

So what is so troubling about this ruling? A couple of things. First, the Pitsilides court described the en banc Range II decision as turning on several factors, including having “lived an essentially law-abiding life since” the 25-year-old crime, had no history of violence, “had never knowingly violated 922(g)(1)’s prohibition while subject to it, posed no risk of danger to the public, and then filed a declaratory judgment action seeking authorization to bear arms prospectively.” The holding suggests that whether the F-I-P statute can constitutionally be applied to a defendant depends on him or her first seeking government permission (in the form of a declaratory ruling) before possessing a gun.

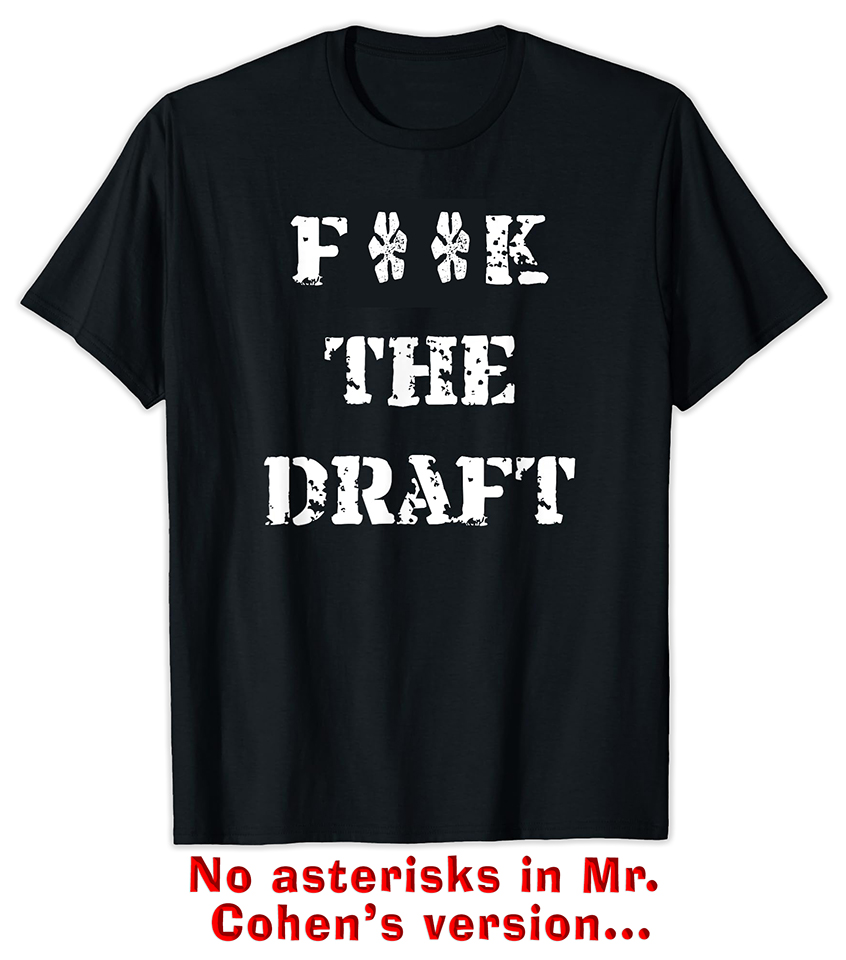

Imagine this standard being applied to free speech: A state law making the wearing clothing emblazoned with the phrase “f**ck the draft” a crime because of the exhibition of an obscene word would violate the 1st Amendment only if the wearer had not violated the unconstitutional statute to begin with and had won a judicial holding that the statute was unconstitutional before donning the offending shirt. (The shirt was the featured garb in Cohen v. California).

Imagine this standard being applied to free speech: A state law making the wearing clothing emblazoned with the phrase “f**ck the draft” a crime because of the exhibition of an obscene word would violate the 1st Amendment only if the wearer had not violated the unconstitutional statute to begin with and had won a judicial holding that the statute was unconstitutional before donning the offending shirt. (The shirt was the featured garb in Cohen v. California).

The second problem is with the squishiness of the term “dangerousness.” As Ohio State law professor Doug Berman aptly described the issue in his Sentencing Law and Policy blog earlier this week:

I have dozens of questions about how a “dangerousness” standard is to apply in the 2nd Amendment context, and I will flag just a few here.

For starters, there are many folks who were clearly dangerous, and were convicted of possibly dangerous crimes in their twenties, who thereafter mature and are no clearly longer dangerous years later. Do these folks have 2nd Amendment rights? More broadly, data show that women as a class are much less likely to commit violent crimes than men, so does this suggest women with criminal records are more likely to have 2nd Amendment rights than men because they are, generally speaking, less dangerous? And, procedurally, who has burden on the issue of “dangerousness” in civil and criminal cases? I assume Pitsilides will have to prove by a preponderance that he is not dangerous in this civil case that he brought, but does the Government now need to prove dangerousness beyond a reasonable doubt in every 18 USC 922(g) criminal prosecution?

The F-I-P “as applied” 2nd Amendment battle is just warming up.

Pitsilides v. Barr, Case No. 21-3320, 2025 U.S. App. LEXIS 3007 (3d Cir. Feb. 10, 2025)

Sentencing Policy and Law, Third Circuit panel states “Second Amendment’s touchstone is dangerousness” when remanding rights claim by person with multiple gambling-related offenses (February 12, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root