We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

ROACH MOTEL

Besides the obvious fact that society abhors sex crimes against children – including the possession of kiddie porn – one of the rationales for handing out Draconian sentences to defendants convicted of such offenses is that they pose such a danger to the public if they’re roaming free.

Everyone knows that’s true. After all, the Supreme Court itself has recognized that an “frightening and high” percentage of untreated child porn offenders “re-offend” – which is sociologist-speak for “commits the same crime again” – after release. The statistic everyone loves to cite is 80%.

Except it now appears that the statistic is wrong. But like roaches at the Roach Motel, the “alternate fact” has checked into federal jurisprudence, and it shows no sign of checking out.

Except it now appears that the statistic is wrong. But like roaches at the Roach Motel, the “alternate fact” has checked into federal jurisprudence, and it shows no sign of checking out.

A New York Times article published last Monday took the State of North Carolina to task for an argument its attorney made during the Supreme Court oral argument the week before in Packingham v. North Carolina. “This court has recognized that [sex offenders] have a high rate of recidivism and are very likely to do this again,” attorney Robert C. Montgomery told the court during his defense of a state law that bars sex offenders from using social media services.

Attorney Montgomery was literally correct. The Supreme Court observed in a 2003 decision, Smith v. Doe, that the risk that sex offenders will commit new crimes is “frightening and high.” The Times said the holding, in a decision affirming Alaska’s sex offender registration law, has been “exceptionally influential. It has appeared in more than 100 lower-court opinions, and it has helped justify laws that effectively banish registered sex offenders from many aspects of everyday life.”

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy’s majority opinion in the 2003 case, Smith v. Doe, cited McKune v. Lile, a decision from the year before, which noted that “[t]he rate of recidivism of untreated offenders has been estimated to be as high as 80 percent.” That decision cited a 1988 Justice Department study entitled A Practitioner’s Guide to Treating the Incarcerated Male Sex Offender, which was a collection of studies by experts in the field. Ironically, most of the recidivism rates cited in the Guide showed slight recidivism rates for sex offenders. One source, however, claimed an 80% re-offense rate, a number that the Guide itself cautioned might be an outlier.

That source was a 1988 article published in the popular trade magazine Psychology Today. The Psychology Today piece simply asserted that “most untreated sex offenders released from prison go on to commit more offenses – indeed, as many as 80% do.” This statistic was not supported by any empirical evidence. In a recent Boston College Law Review article, Dr. Melissa Hamilton (who is both a criminologist and a lawyer) writes, “The Psychology Today authors were therapists in a sex offender treatment program with no apparent academic research credentials or statistical training. Evidently, the authors’ “statistic” was simply based on personal observations from their local treatment program.”

That source was a 1988 article published in the popular trade magazine Psychology Today. The Psychology Today piece simply asserted that “most untreated sex offenders released from prison go on to commit more offenses – indeed, as many as 80% do.” This statistic was not supported by any empirical evidence. In a recent Boston College Law Review article, Dr. Melissa Hamilton (who is both a criminologist and a lawyer) writes, “The Psychology Today authors were therapists in a sex offender treatment program with no apparent academic research credentials or statistical training. Evidently, the authors’ “statistic” was simply based on personal observations from their local treatment program.”

Hamilton argues that

In sum, a principal foundation on which the Supreme Court approved the existence of specialized sex offender policies rested upon virtually no scientific grounds showing that sex offenders are actually at high risk of reoffending. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court’s scientifically dubious guidance on the actual risk of recidivism that sex offenders pose has been unquestionably repeated by almost all other lower courts that have upheld the public safety need for targeted sex offender restrictions.

That may soon change. Pending before the Supreme Court is a petition for writ of certiorari in Doe v. Snyder, the 6th Circuit’s maverick decision to reject the “frightening and high” recidivism canard, in holding that Michigan’s civil sex offender law is unconstitutional. Hamilton argues that “Snyder’s engagement with scientific evidence has the potential to change the jurisprudence surrounding sex offender laws.”

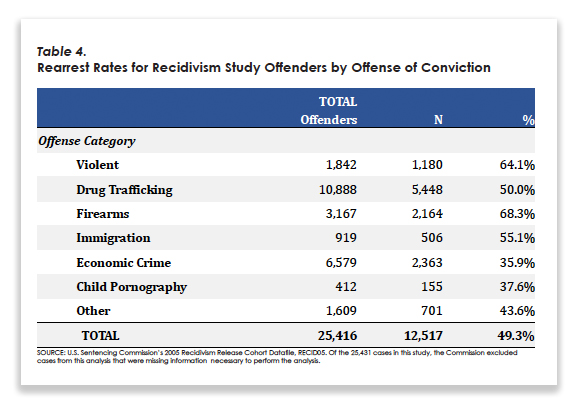

With the Doe v. Snyder certiorari issue to be decided in the next few weeks, the argument against the 80% figure gain traction yesterday with a U.S. Sentencing Commission release of The Past Predicts the Future: Criminal History & Recidivism of Federal Offenders. The study, which is third in a USSC series on the topic, reported that persons convicted of child pornography had a recidivism rate of 37.6%, lower than any other category of offense except economic crimes (which, at 35.9%, was almost indistinguishable). Violent crime offenders, by contrast, reoffended at a 64.1% rate, and drug traffickers at a 50.0% rate.

With the Doe v. Snyder certiorari issue to be decided in the next few weeks, the argument against the 80% figure gain traction yesterday with a U.S. Sentencing Commission release of The Past Predicts the Future: Criminal History & Recidivism of Federal Offenders. The study, which is third in a USSC series on the topic, reported that persons convicted of child pornography had a recidivism rate of 37.6%, lower than any other category of offense except economic crimes (which, at 35.9%, was almost indistinguishable). Violent crime offenders, by contrast, reoffended at a 64.1% rate, and drug traffickers at a 50.0% rate.

Benjamin Disraeli (or Mark Twain, no one’s really sure) famously said, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” He has a “frightening and high” 80% chance of being right.

Benjamin Disraeli (or Mark Twain, no one’s really sure) famously said, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” He has a “frightening and high” 80% chance of being right.

New York Times, Did the Supreme Court Base a Ruling on a Myth? (Mar. 6, 2017)

Hamilton, Constitutional Law and the Role of Scientific Evidence: The Transformative Potential of Doe v. Snyder, 58:E.Supp Boston College Law Review, (2017)

U.S. Sentencing Commission, The Past Predicts the Future: Criminal History & Recidivism of Federal Offenders (Mar. 9, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root