We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

“SEPARATE OCCASIONS” ACCA FINDING MUST BE BY JURY

In an unusual 6-3 lineup (with a vigorous dissent by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who is widely assumed to be defendant-friendly), the Supreme Court ruled last week that the 5th and 6th Amendments require that imposing an Armed Career Criminal Act sentence on a convicted felon in possession of a firearm requires a jury, not a judge.

The ACCA (18 USC 924(e)) imposes a mandatory 15-year prison term on a defendant convicted of being a felon in possession of a gun or ammo who has previously committed three violent felonies or serious drug offenses on separate occasions. Up to now, judges have made decisions on whether occasions were “separate” by a preponderance of the evidence. However, the Supremes hold that as an element of the offense, whether the felonies occurred on separate occasions, must be found by a jury and that the standard should be “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The ACCA (18 USC 924(e)) imposes a mandatory 15-year prison term on a defendant convicted of being a felon in possession of a gun or ammo who has previously committed three violent felonies or serious drug offenses on separate occasions. Up to now, judges have made decisions on whether occasions were “separate” by a preponderance of the evidence. However, the Supremes hold that as an element of the offense, whether the felonies occurred on separate occasions, must be found by a jury and that the standard should be “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

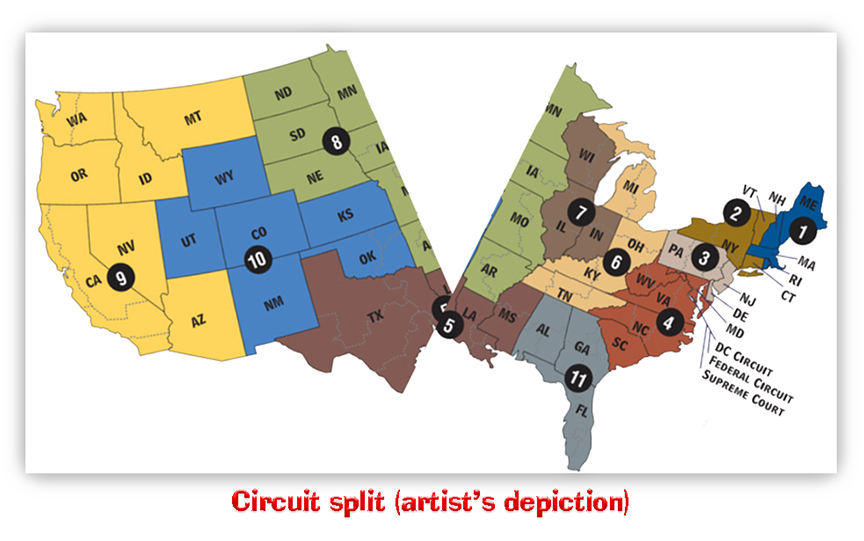

Up to now, circuits have been split on whether a judge or a jury had to find that the three occasions were different. A Supreme Court opinion two years ago, Wooden v. United States, established standards for deciding when offenses had been committed on “different occasions.” Now, how those standards are to be decided has broken in favor of defendants as well.

Up to now, circuits have been split on whether a judge or a jury had to find that the three occasions were different. A Supreme Court opinion two years ago, Wooden v. United States, established standards for deciding when offenses had been committed on “different occasions.” Now, how those standards are to be decided has broken in favor of defendants as well.

A surprising twist in the case was that the government agreed with the defendant that the element should be found by a jury beyond a reasonable doubt:

Petitioner renews his contention that the 6th Amendment requires a jury to find (or a defendant to admit) that predicate offenses were under the ACCA. In light of this Court’s recent articulation of the standard for determining whether offenses occurred on different occasions in Wooden v United States, the government agrees with that contention. Although the government has opposed previous petitions raising this issue, recent developments make clear that this Court’s intervention is necessary to ensure that the circuits correctly recognize defendants’ constitutional rights in this context. This case presents a suitable vehicle for deciding the issue this Term and thereby providing the timely guidance that the issue requires.

The decision is yet another chink in the armor of Almendarez-Torres v. United States, which permits a judge instead of a jury to find certain facts related to a defendant’s past offenses. That decision is at odds with Apprendi v New Jersey, which held that the elements of any statute that increased the statutory sentencing range had to be decided by a jury beyond a reasonable doubt.

The decision is yet another chink in the armor of Almendarez-Torres v. United States, which permits a judge instead of a jury to find certain facts related to a defendant’s past offenses. That decision is at odds with Apprendi v New Jersey, which held that the elements of any statute that increased the statutory sentencing range had to be decided by a jury beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Erlinger majority described Almendarez-Torres as “an outlier” and “at best an exceptional departure” from historic practice.

Erlinger v. United States, Case No 23-370, 2024 U.S. LEXIS 2715 (June 21, 2024)

Almendarez-Torres v. United States, 523 U.S. 224 (1998)

Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000)

– Thomas L. Root

Simon Brewster was on trial in state court for bank robbery. The jury went out, but reported to the judge a few hours later that it was hopelessly deadlocked 9-3 for conviction. The judge gave the jury the

Simon Brewster was on trial in state court for bank robbery. The jury went out, but reported to the judge a few hours later that it was hopelessly deadlocked 9-3 for conviction. The judge gave the jury the