We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

FRAUD STORM BREWING OVER 3RD CIRCUIT BANKS RULING?

A defense attorney calls it “really a potential sea change in federal sentencing,” Bloomberg Law reported last week.

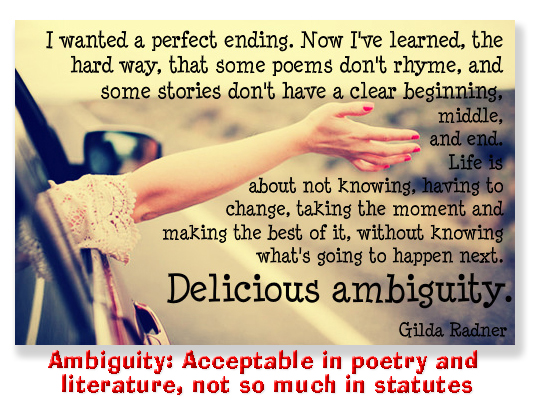

A year ago, the 3rd Circuit held in United States v. Banks that the loss enhancement under USSG § 2B1.1(b)(1) – the linchpin of economic crimes sentencing – is limited to actual loss. Relying on the 2019 Supreme Court Kisor v. Wilkie decision, the 3rd applied the ordinary meaning of “loss” to determine that § 2B1.1 includes only what was lost because the word “intended” is only mentioned in the § 2B1.1 commentary. The Circuit held that “the loss enhancement in the Guideline’s application notes impermissibly expands the word ‘loss’ to include both intended loss and actual loss.”

A year ago, the 3rd Circuit held in United States v. Banks that the loss enhancement under USSG § 2B1.1(b)(1) – the linchpin of economic crimes sentencing – is limited to actual loss. Relying on the 2019 Supreme Court Kisor v. Wilkie decision, the 3rd applied the ordinary meaning of “loss” to determine that § 2B1.1 includes only what was lost because the word “intended” is only mentioned in the § 2B1.1 commentary. The Circuit held that “the loss enhancement in the Guideline’s application notes impermissibly expands the word ‘loss’ to include both intended loss and actual loss.”

Bloomberg reported that the ruling has sparked a debate on how much deference to give the Sentencing Commission’s interpretation of its own Guidelines, including the loss scale that can dramatically increase the sentencing range in fraud crimes. The Guideline suggests in the commentary using the greater of actual or intended loss when determining sentences. But the 3rd said the USSC lacked authority to expand the meaning of “loss” to include what was intended but did not happen.

“We are getting these absurd results where nonviolent criminals are getting extraordinary sentences,” one defense attorney told Bloomberg.

Bloomberg said Banks “could significantly reduce prison time for defendants in securities and commodities cases since it is difficult to figure out actual losses in those situations… It could also impact charging decisions, especially in 3rd Circuit territory, where prosecutors may think twice about devoting resources to cases with small actual losses.”

Bloomberg said Banks “could significantly reduce prison time for defendants in securities and commodities cases since it is difficult to figure out actual losses in those situations… It could also impact charging decisions, especially in 3rd Circuit territory, where prosecutors may think twice about devoting resources to cases with small actual losses.”

But in the year since Banks was decided, defense attorneys have had limited success using the decision outside of the 3rd Circuit. In December, an Eastern District of _ichigan court in United States v. McKinney sided with the Banks ruling in a case involving a defendant who pleaded guilty to fraud against JPMorgan Chase. The judge reasoned that she didn’t have to defer to the Sentencing Commission because the definition of loss isn’t “genuinely ambiguous.” Later, the 6th Circuit cast some shade on relying on Banks in United States v. Xiaorong You, holding in a trade secrets theft case that “Banks’s attempt to impose a one-size-fits-all definition is not persuasive” and that the Guidelines commentary is entitled to deference.

Two other circuits, the 1st and 4th Circuits, have declined to take a position. In United States v. Limbaugh, the 4th declined to apply F.R.Crim.P. 52(b) “plain error” to an “intended loss” sentence, holding that the Banks holding “is a new and fast-developing area of the law, and as of now, we do not have the kind of robust consensus in other circuits that would allow us to label as “plain” any error committed here.” The 1st Circuit did the same in United States v. Gadson.

The issue is tied up with a 1993 SCOTUS ruling in Stinson v. United States that held Guidelines commentary is authoritative unless it violates the Constitution, violates a federal statute, or is inconsistent with, or a plainly erroneous reading of, the applicable Guideline. The 4th, 6th, 9th, and 11th Circuits all agree with the 3rd’s position that the Supreme Court in Kisor v. Willkie replaced Stinson’s highly deferential standard — to guideline commentary, at least — with a less deferential one.

However, some other circuit courts have taken the opposite view. The 5th Circuit is the latest, ruling in the en banc United States v. Vargas decision that while the Guidelines are silent on the treatment of conspiracies, its commentary includes them and thus subjects a defendant to increased prison time. In deferring to the commentary, the 5th held that it is bound to follow Stinson, “like night follows day.” Under Stinson, the court went on to explain, the commentary is authoritative unless it is inconsistent with, or a plainly erroneous reading of, the applicable guideline.

However, some other circuit courts have taken the opposite view. The 5th Circuit is the latest, ruling in the en banc United States v. Vargas decision that while the Guidelines are silent on the treatment of conspiracies, its commentary includes them and thus subjects a defendant to increased prison time. In deferring to the commentary, the 5th held that it is bound to follow Stinson, “like night follows day.” Under Stinson, the court went on to explain, the commentary is authoritative unless it is inconsistent with, or a plainly erroneous reading of, the applicable guideline.

Some commentators believe the Supreme Court will need to decide the issue. While SCOTUS has not taken up the issue, it will address Chevron deference this term, and the outcome of that could presage, if not settle, the Banks issue.

Bloomberg Law, Wall Street Fraudsters Rush to Cut Prison Terms With New Ruling (November 1, 2023)

United States v. Banks, 55 F.4th 246 (3d Cir, Nov 30, 2022)

United States v. McKinney, 645 F. Supp. 3d 709 (E.D. Mich. 2022)

United States v. Xiaorong You, 74 F.4th 378 (6th Cir. 2023)

United States v. Limbaugh, No. 21-4449, 2023 U.S. App. LEXIS 317 (4th Cir., Jan. 6, 2023)

United States v. Gadson, 77 F.4th 16 (1st Cir. 2023)

Kisor v. Wilkie, 588 U.S. —, 139 S. Ct. 2400, 204 L. Ed. 2d 841 (2019)

Stinson v. United States, 508 U.S. 36 (1993)

United States v. Vargas, 77 F.3d 673 (5th Cir. 2023) (en banc)

Federalist Society, How Much Should Courts Defer to U.S. Sentencing Guidelines Commentary? (August 9, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root