We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

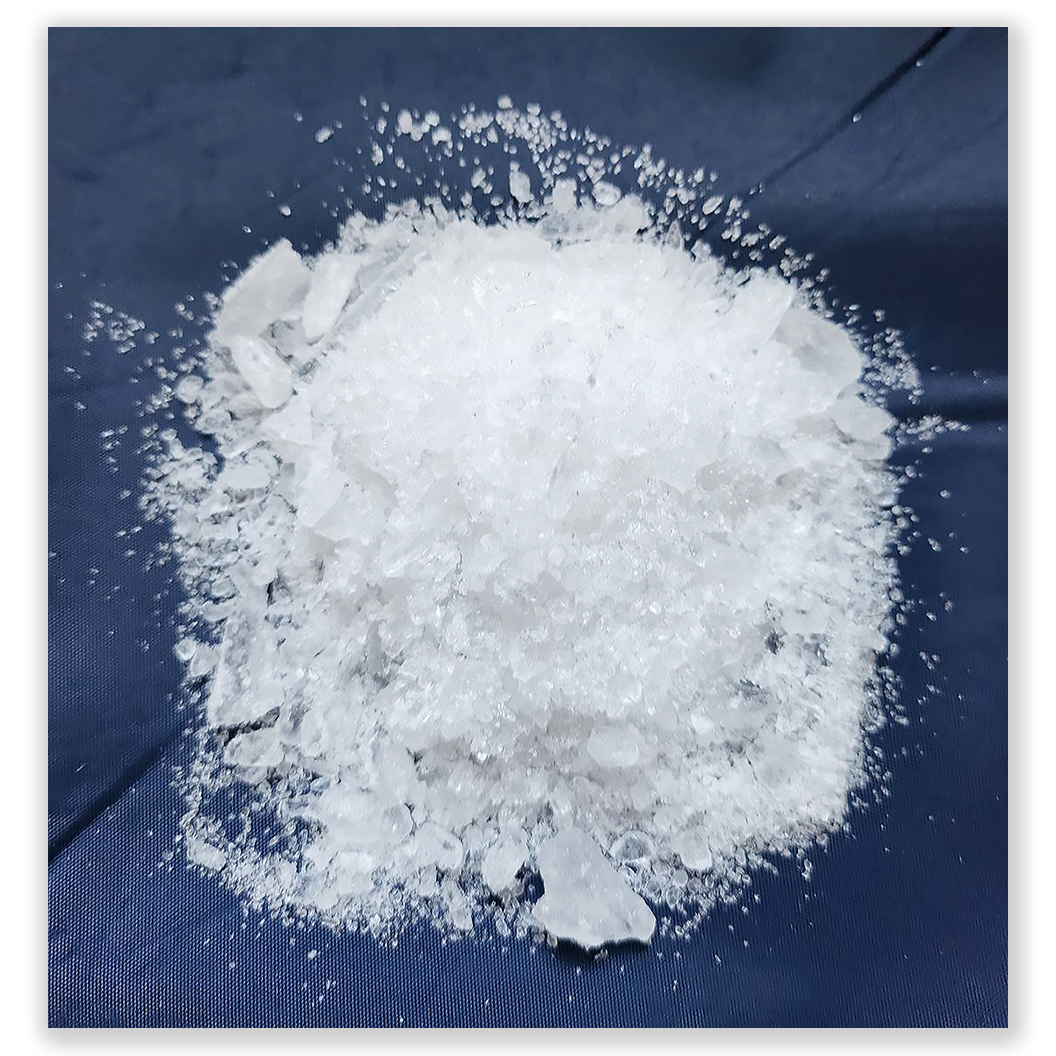

‘ICE’ MAY BE MELTING

In December, the United States Sentencing Commission announced proposed Sentencing Guidelines amendments for public comment on the sweeping if rather tedious topics of guideline simplification, criminal history, firearm offenses, circuit conflicts and retroactivity.

At the time, Sentencing Commission Chairman, Judge Carlton W. Reeves (Southern District of Mississippi) hinted that the USSC could be announcing some additional proposed amendments this month.

At the time, Sentencing Commission Chairman, Judge Carlton W. Reeves (Southern District of Mississippi) hinted that the USSC could be announcing some additional proposed amendments this month.

Last Friday, the Commission provided an upbeat end to a tough week for federal criminal justice, proposing defendant-friendly amendments to Guidelines on supervised release, the drug quantity tables, and enhanced offense levels for “ice” and pure methamphetamine.

The draft amendments, released for public comment, also propose cracking down on distribution of drugs laced with fentanyl as well as an increased enhancement for packing a machine gun during a drug crime.

The biggest surprise is a proposed change to adopt one of three options, any of which would reduce the top base offense level for drug quantity in the Guidelines. A Guidelines sentence for a drug offender is driven by the weight of the drugs attributed to him or her. If Tom the Trafficker, with no prior convictions, was involved in a cocaine conspiracy that sold 1,000 lbs of cocaine (10 lbs. a week) over two years – even if he only sold an 8-ball a day five days a week for two years (about 4 lbs) – his Guidelines base offense level would be 38 with a sentencing range starting at 20 years in prison.

The three options the Sentencing Commission is considering would drop the levels in the drug quantity table to Level 30, 32 or 34 instead of the current 38. At Level 30, our hypothetical Tom would be looking at an advisory sentencing range of 8 years instead of 20.

The Commission said it “has received comment over the years indicating that [Guideline] 2D1.1 overly relies on drug type and quantity as a measure of offense culpability and results in sentences greater than necessary to accomplish the purposes of sentencing.”

The second proposed amendment would essentially wipe out the drug quantity table’s 10-to-1 focus on meth purity and eliminate any enhanced penalty for crystal meth, known as “ice.” Commission data show that in the last 22 years, the offenses involving meth mixtures has remained steady while the number of offenses involving “meth (actual)” and “ice” have risen substantially. A recent Commission report found that today’s meth is “highly and uniformly pure, with an average purity of 93.2% and a median purity of 98.0%.”

The second proposed amendment would essentially wipe out the drug quantity table’s 10-to-1 focus on meth purity and eliminate any enhanced penalty for crystal meth, known as “ice.” Commission data show that in the last 22 years, the offenses involving meth mixtures has remained steady while the number of offenses involving “meth (actual)” and “ice” have risen substantially. A recent Commission report found that today’s meth is “highly and uniformly pure, with an average purity of 93.2% and a median purity of 98.0%.”

In other words, if all meth is pure, applying the higher base offense level for pure meth becomes the norm rather than the exception. This is a drug-crime equivalent of the Lake Wobegon effect, humorist Garrison Keilor’s representation that in Lake Wobegon, all the children are above average.

The meth purity change could decrease Guideline base offense levels by up to 4.

A note: Judge Reeves, wearing his district court hat instead of USSC hat, wrote a thoughtful opinion two years ago in which he refused to apply the purity enhancement on the same grounds that the Commission cites now as a rationale for changing the Guidelines.

The other significant change is to supervised release, which would dramatically reduce the cases in which it is added to the end of a sentence. Among its many changes – focused on making supervised release more about rehabilitation and less about punishment – the proposed amendment would also adopt inmate-friendly standards for early termination of supervised release, making getting off supervised release after a year much easier to do.

The other significant change is to supervised release, which would dramatically reduce the cases in which it is added to the end of a sentence. Among its many changes – focused on making supervised release more about rehabilitation and less about punishment – the proposed amendment would also adopt inmate-friendly standards for early termination of supervised release, making getting off supervised release after a year much easier to do.

The Sentencing Commission proposal says nothing about whether the drug quantity table reduction or meth changes – if they are adopted – would be retroactive. Retroactivity would be decided in a separate proceeding, and the USSC is in the middle of a painful re-evaluation of when and whether retroactivity should be allowed.

For now, the proposed amendments will be out for public comment until March 3, 2025, with reply comments due by March 18, 2025. The Commission will decide what it will adopt as final amendments by May 1, and those will become effective (absent Congressional veto) on November 1, 2025.

US Sentencing Commission, Proposed Amendments to the Sentencing Guidelines (Preliminary) (January 24, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root