We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

NO DEFENDANT LEFT BEHIND

The 2015 Supreme Court decision Johnson v. United States was a landmark, holding that the residual clause in the Armed Career Criminal Act’s definition of “crime of violence” was unconstitutionally vague. Johnson’s reasoning led to Sessions v. Dimaya (extending Johnson to the criminal code’s general definition of “crime of violence” at 18 USC § 16(b)) and 2019’s United States v. Davis holding extending Johnson to 18 USC § 924(c), the “use or carry a firearm” statute.

The 2015 Supreme Court decision Johnson v. United States was a landmark, holding that the residual clause in the Armed Career Criminal Act’s definition of “crime of violence” was unconstitutionally vague. Johnson’s reasoning led to Sessions v. Dimaya (extending Johnson to the criminal code’s general definition of “crime of violence” at 18 USC § 16(b)) and 2019’s United States v. Davis holding extending Johnson to 18 USC § 924(c), the “use or carry a firearm” statute.

But thousands of inmates who were held to be Guidelines “career offenders” because of prior crimes of violence got no relief. A Guidelines “career offender” is very different from an ACCA armed career criminal. A Guidelines career offender is someone with two prior crimes of violence or serious drug convictions (federal or state). If a defendant qualifies as a Guidelines career offender, he or she will be deemed to have the highest possible criminal history score and a Guidelines offense level that ensures a whopping sentencing range.

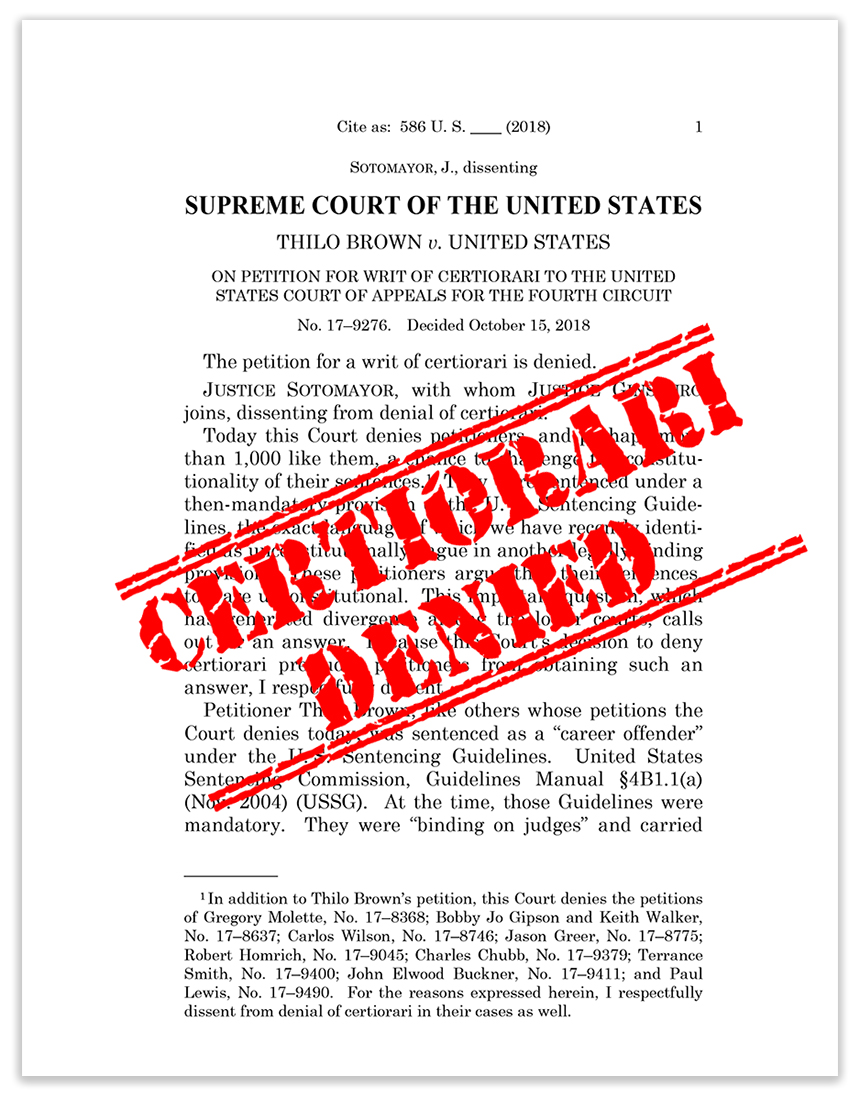

After Johnson, a number of Guidelines career offenders, whose status had been fixed by including some dubious prior convictions as “violent,” sought the same kind of relief that Johnson afforded armed career criminals. But in 2017 the Supremes said that Johnson did not apply to the Guidelines. Beckles v. United States held that the Guidelines were not subject to the same kind of “vagueness” challenge that worked in Johnson, because the Guidelines did not “fix the permissible range of sentences, but merely guided the exercise of discretion in choosing a sentence within the statutory range.”

This may have been so for people sentenced under the advisory Guidelines. However, back before the 2005 Supreme Court decision in United States v. Booker, those “advisory” Guidelines were mandatory. They did not guide a judge’s discretion. Instead, the law required a judge to sentence within the applicable Guidelines sentencing range except in very narrow circumstances, and then only if the sentencing court jumped through the many hoops the Guidelines erected.

So, how about guys like Tony Shea, who was sentenced after a bank robbery spree as a career offender back in 1998? Tony’s prior crimes of violence were pretty shaky bases for a career offender enhancement (not that Tony didn’t have plenty of problems for his string of armed robberies, but that’s another story). Tony was looking at minimum 430 months under normal Guidelines, nothing to sneeze at, but with the career offender label, Tony’s minimum sentence shot that up to 567 months (that’s 47-plus years, or 330 dog years).

So, how about guys like Tony Shea, who was sentenced after a bank robbery spree as a career offender back in 1998? Tony’s prior crimes of violence were pretty shaky bases for a career offender enhancement (not that Tony didn’t have plenty of problems for his string of armed robberies, but that’s another story). Tony was looking at minimum 430 months under normal Guidelines, nothing to sneeze at, but with the career offender label, Tony’s minimum sentence shot that up to 567 months (that’s 47-plus years, or 330 dog years).

Tony filed a § 2255 motion arguing that because his Guidelines career offender sentence was mandatory, not “advisory,” the Johnson holding should apply to wipe out his career offender status.

Last Monday, the 1st Circuit agreed. The appeals court noted that while Beckles was right that advisory Guidelines guide a judge’s discretion rather than “fix the permissible range of sentences,” the pre-Booker Guidelines did much more than this. The Circuit said “when the pre-Booker Guidelines ‘bound the judge to impose a sentence within’ a prescribed range, as they ordinarily did, they necessarily “fixed the permissible range of sentences” she could impose.”

“It’s easy,” the 1st said “to see why vague laws that fix sentences… violate the Due Process Clause. The… rule applied in Booker serves two main functions. First, fair notice: requiring the indictment to allege ‘every fact which is legally essential to the punishment to be inflicted… enables the defendant to determine the species of offence with which he is charged in order that he may prepare his defense accordingly…” Second, “the rule also guards against the threat of ‘judicial despotism’ that could arise from ‘arbitrary punishments upon arbitrary convictions,’ by requiring the jury to find each fact the law makes essential to his punishment.”

Only the 11th Circuit has explicitly held that Beckles does not apply to mandatory Guidelines career offender enhancements. The 5th, 8th and 10th Circuits are on the fence. This 1st Circuit decision is the first to emphatically apply Johnson to give relief to people like Tony, who is already well into his third decade of imprisonment.

Shea v. United States, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 30776 (1st Cir., September 28, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root