We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

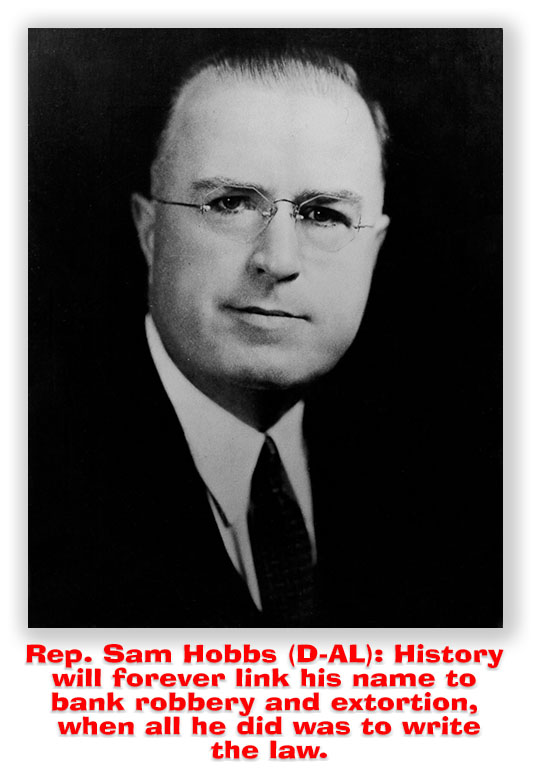

9TH CIRCUIT HOLDS HOBBS ACT AIDER AND ABETTOR COMMITS CRIME OF VIOLENCE

Call me dense (you wouldn’t be the first), but I have never understood how an attempt to commit a Hobbs Act robbery could not be a crime of violence – as the Supreme Court held in United States v. Taylor – but aiding and abetting a Hobbs Act robbery was a crime of violence under 18 USC § 924(c)(1)(A)(3).

In Taylor, the Supremes held that attempted Hobbs Act robbery was not a crime of violence, because one could attempt a Hobbs Act robbery without actually attempting, threatening or using violence. If, for example, Peter Perp is arrested in a jewelry store parking lot with masks and a gun as he approaches the front door, he could be convicted of an attempted Hobbs Act robbery without ever having gotten to the point of attempting to threaten or employ violence at all. In fact, the people inside the store might not even be aware that they were about to be robbed. Sure, Petey can go down for an attempted Hobbs Act robbery (and get plenty of time for that), but he could not be convicted of a § 924(c) offense.

In Taylor, the Supremes held that attempted Hobbs Act robbery was not a crime of violence, because one could attempt a Hobbs Act robbery without actually attempting, threatening or using violence. If, for example, Peter Perp is arrested in a jewelry store parking lot with masks and a gun as he approaches the front door, he could be convicted of an attempted Hobbs Act robbery without ever having gotten to the point of attempting to threaten or employ violence at all. In fact, the people inside the store might not even be aware that they were about to be robbed. Sure, Petey can go down for an attempted Hobbs Act robbery (and get plenty of time for that), but he could not be convicted of a § 924(c) offense.

Taylor seemed to focus on what elements would have to be proven for the particular defendant to be convicted of the Hobbs Act crime. The principals in the crime – the guys who actually waved guns in the jewelry store clerks’ faces – must be shown to have employed violence or threatened to do so. But how about the guy sitting behind the wheel of the getaway car? He’s aiding and abetting, and certainly can be convicted of the Hobbs Act offense just like the gun-wielders. But that’s not the point. The point is whether he is also guilty of a 924(c) offense, too.

Leon Eckford is as disappointed as I am (maybe more, because he’s doing the time) that the 9th Circuit went the other way on my pet legal argument the other day. Leon pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting two Hobbs Act jewelry store robberies. He was sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment, including a mandatory minimum sentence for the use of a firearm during a crime of violence under § 924(c).

On appeal, Leon argues that aiding and abetting Hobbs Act robbery is not a crime of violence and therefore could not serve as a predicate for his § 924(c) conviction and mandatory minimum sentence. A couple of days ago, the 9th rejected his argument.

On appeal, Leon argues that aiding and abetting Hobbs Act robbery is not a crime of violence and therefore could not serve as a predicate for his § 924(c) conviction and mandatory minimum sentence. A couple of days ago, the 9th rejected his argument.

The Circuit claimed that Leon’s argument “misunderstands the nature of aiding and abetting liability. At common law, aiding and abetting was considered a separate offense from the crime committed by the principal actor, but “we no longer distinguish between principals and aiders and abettors; principals and accomplices “are equally culpable and may be convicted of the same offense.”

The 9th complained that Leon “would have us return to the era when we treated principals and accomplices as guilty of different crimes. We have long moved past such distinctions for purposes of determining criminal culpability, although the terminology may be useful for other reasons.” This is nonsense. Leon freely admitted that his aiding and abetting the Hobbs Act robberies made him as guilty of the offense as if he had been inside the stores. He did not ask to be treated as having been convicted of a “different crime.”

Instead, as the Circuit admitted without appreciating its significance, the law has moved past distinguishing principal versus accomplice “for purposes of determining criminal culpability,” that is, for figuring out whether Leon was guilty of a Hobbs Act offense. But, as the 9th admitted, “the terminology may be useful for other reasons.”

Primary among those reasons is to determine whether the defendant’s commission of the Hobbs Act was a crime of violence. This is not to say that the court should focus on what Leon himself did. The categorical approach to determining whether aiding and abetting a Hobbs Act robbery is violent does not look at the facts of the case. Instead, it focuses on what must be proven to prove a defendant was an aider-and-abettor.

Primary among those reasons is to determine whether the defendant’s commission of the Hobbs Act was a crime of violence. This is not to say that the court should focus on what Leon himself did. The categorical approach to determining whether aiding and abetting a Hobbs Act robbery is violent does not look at the facts of the case. Instead, it focuses on what must be proven to prove a defendant was an aider-and-abettor.

The 9th Circuit noted that it had “repeatedly upheld § 924(c) convictions based on accomplice liability.” So what? The 9th Circuit had previously held that an attempted Hobbs Act robbery was a crime of violence until Taylor reversed the holding. Being wrong once is hardly an argument that you aren’t wrong now.

The Circuit argues that nothing in its analysis in Leon’s case is “clearly irreconcilable with Taylor. Taylor dealt with an inchoate crime, an attempt, and does not undermine our precedent on aiding and abetting liability. There are fundamental differences between attempting to commit a crime, and aiding and abetting its commission… Chief among these differences is that in an attempt case there is no crime apart from the attempt, which is the crime itself, whereas aiding and abetting is a different means of committing a single crime, not a separate offense itself. Put differently, proving the elements of an attempted crime falls short of proving those of the completed crime, whereas a conviction for aiding and abetting requires proof of all the elements of the completed crime plus proof of an additional element: that the defendant intended to facilitate the commission of the crime.

The 9th held that “[o]ne who aids and abets the commission of a violent offense has been convicted of the same elements as one who was convicted as a principal; the same is not true of one who attempts to commit a violent offense. Accordingly, we conclude that our precedent is not clearly irreconcilable with Taylor.”

The 9th held that “[o]ne who aids and abets the commission of a violent offense has been convicted of the same elements as one who was convicted as a principal; the same is not true of one who attempts to commit a violent offense. Accordingly, we conclude that our precedent is not clearly irreconcilable with Taylor.”

But if 924(c) is intended to fix extra liability for using a gun in a crime of violence, the element that the defendant employed or threatened violence should be required.

United States v. Eckford, Case No. 17-50167, 2023 U.S. App. LEXIS 21175 (9th Cir. Aug. 15, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root