We’re still doing a weekly newsletter… we’re just posting pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way…

YESTERDAY’S NEWS

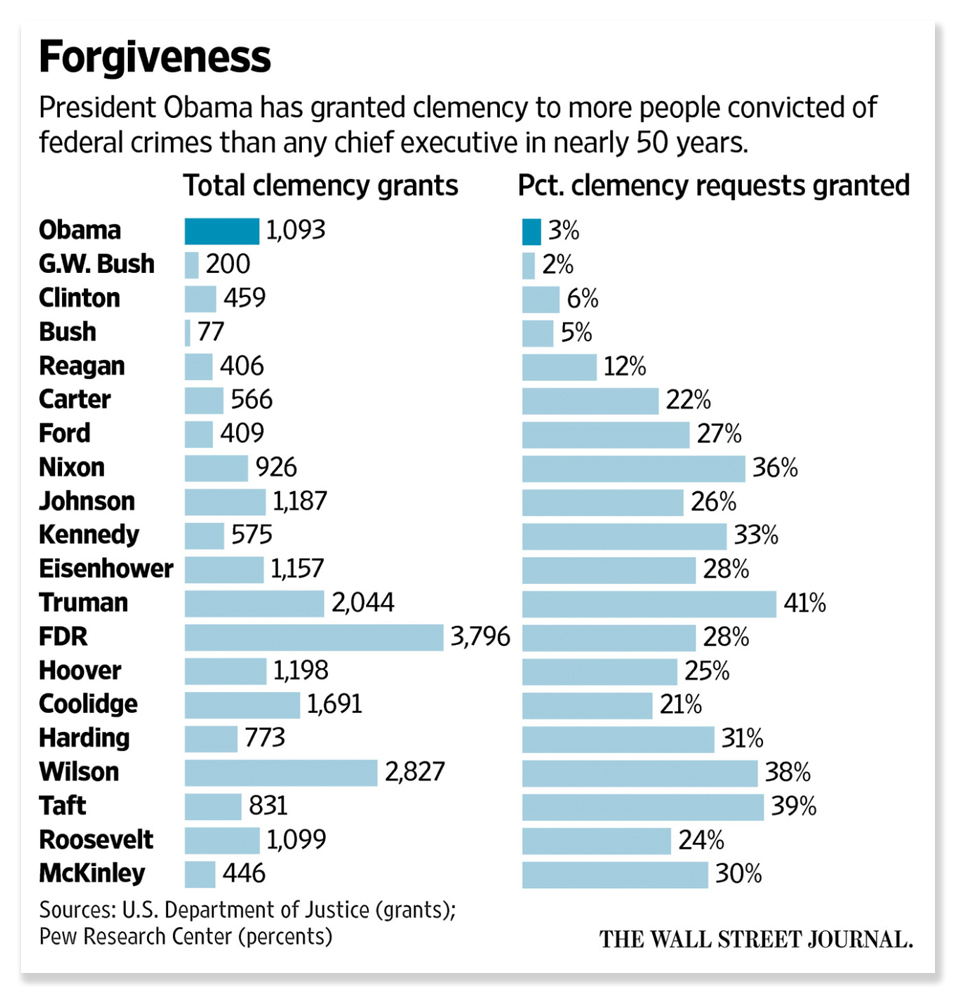

Criminal justice news was dominated yesterday by more Obama Administration grandstanding on clemency, as the outgoing President commuted 153 sentences and pardoned another 78 people who had already done their time. Although the pardons spanned a variety of offenses from perjury to manslaughter, the commutations were again all for drug offenders.

None of the pardoned offenders was Hillary Clinton, Chelsea (née Bradley) Manning or Edward Snowden. Deputy Attorney General Sally Q. Yates said Obama is not done. “Today, another 153 individuals were granted commutations by the President. Over the last eight years, President Obama has given a second chance to over 1,100 inmates who have paid their debt to society. Our work is ongoing and we look forward to additional announcements from the President before the end of his term.”

With yesterday’s announcement, Obama has commuted 62.3% of his self-proclaimed goal of 2,000 sentences. No panic. He still has 30 days left.

With yesterday’s announcement, Obama has commuted 62.3% of his self-proclaimed goal of 2,000 sentences. No panic. He still has 30 days left.

In more interesting news, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit reversed the racketeering convictions of Massachusetts Probation Office chief Jack O’Brien and two other senior officials who had “abused the hiring process to ensure that favored candidates were promoted or appointed in exchange for favorable budget treatment from the state legislature and increased control over the Probation Department.”

The Probation Office had detailed and influence-neutral hiring procedures in place. However, while the senior officials assured Massachusetts judges that the Office was following the handbook, they in fact hired unqualified candidates favored by influential lawmakers to ensure that they maintained “a good rapport with the legislature to facilitate a beneficial budget to the Probation Department.” The scheme unraveled in 2010 when the Boston Globe reported that ‘After 12 years in charge, Jack O’Brien has transformed the Probation Department from a national pioneer of better ways to rehabilitate criminals into an organization that functions more like a private employment agency for the well connected…”

The Probation Office had detailed and influence-neutral hiring procedures in place. However, while the senior officials assured Massachusetts judges that the Office was following the handbook, they in fact hired unqualified candidates favored by influential lawmakers to ensure that they maintained “a good rapport with the legislature to facilitate a beneficial budget to the Probation Department.” The scheme unraveled in 2010 when the Boston Globe reported that ‘After 12 years in charge, Jack O’Brien has transformed the Probation Department from a national pioneer of better ways to rehabilitate criminals into an organization that functions more like a private employment agency for the well connected…”

The Feds, never ones to overlook a chance to capitalize on a high-profile story, obligingly indicted the three under the Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, 18 U.S.C. 1962(d). After a 47-day trial, a confused jury convicted them of the RICO conspiracy and a few of the underlying mail-fraud counts, but acquitted them of bribery.

Holding that “not all unappealing conduct is criminal,” the 1st Circuit yesterday held that the RICO charge was not proven. The Court said that just showing that goldbricks and idiots were hired “to build a reservoir of goodwill that might ultimately affect one or more of a multitude of unspecified acts, now and in the future” was not enough: the government had to show that the hiring of sponsored applicants was linked to a specific official act by the sponsor.

Holding that “not all unappealing conduct is criminal,” the 1st Circuit yesterday held that the RICO charge was not proven. The Court said that just showing that goldbricks and idiots were hired “to build a reservoir of goodwill that might ultimately affect one or more of a multitude of unspecified acts, now and in the future” was not enough: the government had to show that the hiring of sponsored applicants was linked to a specific official act by the sponsor.

The Circuit threw out the mail fraud convictions as well. The government argued that use of the mails to send unsuccessful candidates their rejection letters was enough to bring the case under the mail fraud statute, because “such rejection letters in a corrupt hiring system satisfy Sec. 1341‘s mailing element where they help to maintain a facade of a merit-based system.” The appellate court rejected this argument:

The Circuit threw out the mail fraud convictions as well. The government argued that use of the mails to send unsuccessful candidates their rejection letters was enough to bring the case under the mail fraud statute, because “such rejection letters in a corrupt hiring system satisfy Sec. 1341‘s mailing element where they help to maintain a facade of a merit-based system.” The appellate court rejected this argument:

The Government presented no evidence that would allow the jury to infer that the rejection letters in this case served this duplicitous function. Had unsuccessful applicants received no notice, they may have assumed they were not hired or else called OCP to check their status. The Government identifies language in the rejection letters stating that “[t]he selection of the final candidate was a difficult process” and that the deputy commissioners “were very impressed with [the recipients’] qualifications” to demonstrate that the letters were intended to convince rejected candidates that their selection was based on merit. We are not convinced that such vague platitudes, hallmarks of any rejection letter, sufficiently demonstrate that the rejections had any real tendency to convey a merit-based selection system.

The Court also dismissed Government arguments that the rejection letters “tended to perpetuate the scheme by making the rejected applicant less likely to call to inquire as to his status, thereby making it less likely that such a call might lead to some inquiry that would uncover the scheme.” The Court characterized this argument as “rank speculation,” saying that the” Government’s evidence provided no plausible mechanism by which a call from a rejected applicant asking about his or her status would lead to the discovery of the scheme.”

Clearly, the 1st Circuit panel found the Government’s use of RICO – originally intended to fight the Mafia – on a two-bit political patronage scheme to be akin to the application of a meat axe where a scalpel would have sufficed.

Clearly, the 1st Circuit panel found the Government’s use of RICO – originally intended to fight the Mafia – on a two-bit political patronage scheme to be akin to the application of a meat axe where a scalpel would have sufficed.

United States v. Tavares, Case No. 14-2313 (1st Cir., Dec. 19, 2016)