We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

FLIGHT OF THE PHOENIX

Congressman Bob Goodlatte (R-Virginia), chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, said yesterday that his agenda for the 115th Congress includes comprehensive sentencing reform, which was subject of a two year-long bipartisan push in both houses of the 114th Congress before being run down and killed by the 2016 elections.

Congressman Bob Goodlatte (R-Virginia), chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, said yesterday that his agenda for the 115th Congress includes comprehensive sentencing reform, which was subject of a two year-long bipartisan push in both houses of the 114th Congress before being run down and killed by the 2016 elections.

Speaking to the Federalist Society at the National Press Club, Goodlatte said, “Both Ranking Member Conyers and I remain committed to passing bipartisan criminal justice reform. We must rein in the explosion of federal criminal laws, protect innocent citizens’ property from unlawful seizures, and enact forensics reforms to identify the guilty and quickly exonerate the innocent. We must also reform sentencing laws in a responsible way and improve the prison system and reentry programs to reduce recidivism.”

Goodlatte’s announcement bookends a week that began with House Oversight Committee Chairman Jason Chaffetz (R-Utah) saying that criminal-sentencing reform proponents in Congress are optimistic that Vice President Mike Pence will be an ally, helping them to work with the Trump administration to pass sentence reform legislation.

“I’ve got reason to be hopeful,” Chaffetz told reporters at a morning session of the Seminar Network, a group of libertarian and conservative donors gathered in Palm Springs by Charles and David Koch.

Even as Congressional Republicans started sliding sentencing reform onto the front burner, CNN darkly warned that “the future of criminal justice reform hangs in the balance as the nomination of Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions, President Donald Trump’s pick for attorney general” was approved in a party-line vote by the Senate Judiciary Committee. CNN cited unidentified “activists” who worried that Trump would “halt former President Barack Obama’s reforms, and institute new policies that could worsen conditions.”

We’re not sure what planet CNN has been on, but we’re fairly confident that Obama’s only criminal justice “reform” of note in eight years – unless you include his arbitrary and gimmicky clemency lottery – was passage of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010. And as for that, Sessions not only voted for the Act, but in fact worked with Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Illinois) in gaining its passage. That Act reduced the sentencing disparity between offenses for crack and powder cocaine from 100:1 to 18:1, a change widely seen as benefitting minorities, whom were statistically more likely to be involved with crack than with the standard powder. Obama loved to talk a good game, but his Administration promised much (remember Eric Holder’s grand “working group to examine Federal sentencing and corrections policy” announced with fanfare in 2009, only to disappear in the Washington swamp, never to be heard from again?) but delivered damn little.

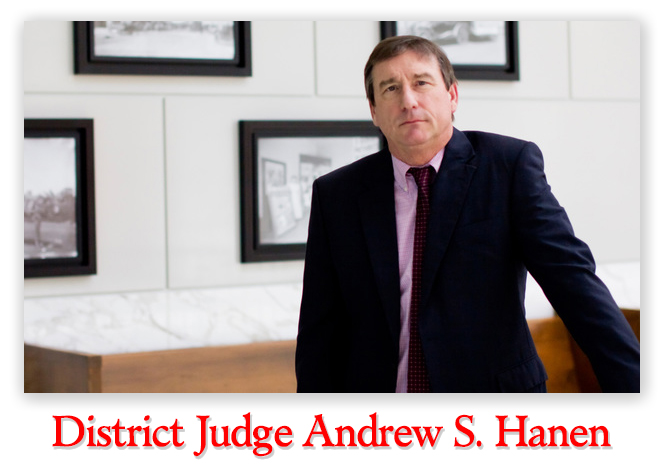

None of this is to suggest that Trump or Sessions share enlightened views on sentencing reform. To the contrary: Trump branded many of the federal prisoners receiving clemency as “bad dudes,” a label applied in usual Trumpian fashion with little reflection and no investigation. As a senator, Sessions was one of the early and vociferous opponents of the Sentence Reform and Corrections Act of 2015, contending that it would “release many dangerous criminals back into American streets.”

.

This might be a plus. With Sessions no longer in the Senate to organize an uber-conservative revolt against sentencing reform, Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas) will stand virtually alone in trying to derail sentence reform. Sure, Sessions may still be against it, but he’ll have much bigger fish to fry over at 9th and Constitution, running the 113,500 employees at DOJ.

As for Trump, will he be an impediment to bipartisan sentencing reform? Who can predict anything with the famously impulsive President? It is noteworthy, however, to observe that last Tuesday in introducing Judge Neil Gorsuch as his nominee for Justice Antonin Scalia’s seat on the Supreme Court, Trump noted of Judge Gorsuch: “While in law school, he demonstrated a commitment to helping the less fortunate. He worked in both Harvard Prison Legal Assistance Projects and Harvard Defenders Program.”

Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman, who writes the Sentencing Law and Policy blog, found it “quite notable that… Prez Trump would stress this history.” Could it be that the President would not be as inalterably opposed to federal sentencing reform as some “activists” might fear?

– Thomas L. Root