We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

RIPPING OFF INMATES

[Corrected on January 29, 2019, to cite that about 1,800 inmates annually receive Rule 35(b) reductions, rather than the incorrect “9,500” figure in the original post – sorry for the error]

Anyone reading what we put out often enough might get the sense that we’re no fans of long prison sentences, or – in many cases – of any prison sentences at all. But there are exceptions, and yesterday, we came across one.

It’s a fairly well known fact that a substantial minority of federal prisoners trade information for lower sentences. We’re down with that: a defendant’s got to do what a defendant’s got to do. Most people who do this jump aboard the train early, but a few go through sentencing without cooperating, only to regret their decision when they walk through the prison doors. For them, there’s Rule 35(b).

It’s a fairly well known fact that a substantial minority of federal prisoners trade information for lower sentences. We’re down with that: a defendant’s got to do what a defendant’s got to do. Most people who do this jump aboard the train early, but a few go through sentencing without cooperating, only to regret their decision when they walk through the prison doors. For them, there’s Rule 35(b).

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 35(b) lets the government file a motion asking that a prisoner’s sentence be cut for post-sentencing cooperation. The Rule 35(b) motion is discretionary on the government’s part, and the sentencing court does not have to grant it. But it works and works well: an average of 1,800 inmates a year received sentence reductions under Rule 35(b) between 2009 and 2014, with the average prisoner getting a 37% sentence cut.

The biggest hurdle for a prisoner seeking a Rule 35(b) sentence reduction is to have some juicy information to trade. After all, the inmate’s locked up, and there are not a lot of opportunities to come up with the kind of first-hand dirt that case agents and U.S. Attorneys like to feast on. In the last decade, inmate scuttlebutt has invented a way around that: third-party Rule 35(b)s.

The concept is simple: the inmate pays someone to arrange a third party on the street to come up with some good confidential information that helps the Feds bag some bad guys. The people with the information ask the U.S. Attorney to credit their information to the inmate, who gets a Rule 35(b) motion for sentence reduction. A real win-win! A bad guy’s off the street, the informant makes some money, and the inmate gets a sentence cut. What could possibly go wrong?

The concept is simple: the inmate pays someone to arrange a third party on the street to come up with some good confidential information that helps the Feds bag some bad guys. The people with the information ask the U.S. Attorney to credit their information to the inmate, who gets a Rule 35(b) motion for sentence reduction. A real win-win! A bad guy’s off the street, the informant makes some money, and the inmate gets a sentence cut. What could possibly go wrong?

Lots. The sad fact is that only a very few courts have granted third-party Rule 35(b) motions, and only when stringent standards are applied. Some courts ban third-party Rule 35(b)s altogether, but the trend is to not turn down a chance for the Feds to enforce the law. The courts that approve them generally require that (1) the inmate play some role in instigating, requesting, providing, or directing the assistance; (2) the government would not have received the assistance but for the inmate’s participation; (3) the assistance is rendered for free; and (4) no other circumstances weigh against rewarding the assistance.

In other words, anyone planning on getting a third-party Rule 35(b) would want to be sure that he or she was personally involved in getting the person to step forward, and that the inmate can easily show that the Government wouldn’t have gotten the help without him or her. Most important, the prisoner had better be absolutely sure that the person providing the assistance is not getting paid anything for it.

In other words, anyone planning on getting a third-party Rule 35(b) would want to be sure that he or she was personally involved in getting the person to step forward, and that the inmate can easily show that the Government wouldn’t have gotten the help without him or her. Most important, the prisoner had better be absolutely sure that the person providing the assistance is not getting paid anything for it.

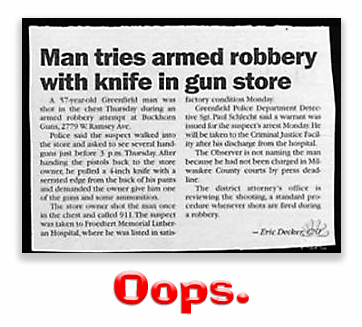

So who does a third-party Rule 35(b) work for? A wife bailing out her husband, a father bailing out his son, brother helping brother… that kind of thing. It definitely does not work for a stranger being paid by an inmate to snitch on another stranger. One can only imagine the field day a defense lawyer would have with a government witness who had been paid under the table by an inmate to inform on someone else.

So a third-party Rule 35(b) cannot happen. But that technicality does not keep inmates from hoping, and where inmates hope, there’s usually someone standing there ready to take their money.

So a third-party Rule 35(b) cannot happen. But that technicality does not keep inmates from hoping, and where inmates hope, there’s usually someone standing there ready to take their money.

Someone like Alvin Warrick. Or maybe we should call him “Pete Candlewood,” one of the aliases he employed as he ripped off federal inmates and their families. “Pete” and his co-conspirators were indicted in federal court for their third-party Rule 35(b) scheme last fall, and a few weeks ago, they pled guilty. Having enjoyed seven rich years living off money they defrauded from inmates’ families, they now are looking forward to seven lean years (at least).

Relatives of at least 22 inmates paid “Pete” and his sidekicks something like $4.4 million, based on their vague promises to set up third-party Rule 35(b) deals. Through a Beaumont, Texas, company called Private Services, “Pete” and his girlfriend Colitha Bush (who went by “Diane Lane”) told the relatives that they “used a network of informants to make undercover drug deals and to provide information and third party cooperation in other criminal cases under the supervision of prosecutors, federal agents, and the courts.” They said that, “if successful, such deals and information would be credited to the inmate and used to secure their early release through a Rule 35 motion.”

Private Services promised families that substantial assistance was being provided to the government on behalf of their inmate loved one. “Pete” even provided fake invoices and phony documents showing that Private Services had inked deals with U.S. Attorneys to provide assistance. In the Factual Proffer “Pete” agreed to in his plea, he admitted that he had “assured and consoled family members of federal inmates that he would work on their case and help to coordinate third party cooperation, but in truth and in fact, and as he well knew, no such work was ever done.”

Private Services promised families that substantial assistance was being provided to the government on behalf of their inmate loved one. “Pete” even provided fake invoices and phony documents showing that Private Services had inked deals with U.S. Attorneys to provide assistance. In the Factual Proffer “Pete” agreed to in his plea, he admitted that he had “assured and consoled family members of federal inmates that he would work on their case and help to coordinate third party cooperation, but in truth and in fact, and as he well knew, no such work was ever done.”

In its usual celebratory press release, the Acting U.S. Attorney for South Florida fulminated, ““Sentencing reduction fraud schemes that prey on the desperation, vulnerability and trust of federal inmates and their families exploit both the victims and the justice system. The U.S. Attorney’s Office in South Florida and our federal partners across the nation will continue to target such schemes and prosecute the offenders.” While we tend to discount government pontification in criminal cases like the media discount President Trump’s tweets, we’re with him on this one.

Apparently, the FBI is still trying to find additional victims. “If you are a victim, it is critical that you reach out to us,” FBI Special Agent in Charge Perrye K. Turner is quoted as saying in the March 30th USAO press release. “This case highlights that justice is blind and underscores the FBI’s impartiality when investigating cases.”

Unsurprisingly, none of “Pete’s” inmate clients received a shorter prison term during the course of the 7-year scheme. Not a one. But the scam was mightly good to “Pete” and “Diane,” who received regular payments from the inmates’ families, which they spent on luxury cars, vacations and gambling.

“Pete” and “Diane” – along with Private Services’ treasurer (who had the sense to make a cooperation deal with the government himself rather than through Private Services) – have signed plea deals. And it’s a fair prediction the inmates’ families will never recover a dime.

“Pete” and “Diane” – along with Private Services’ treasurer (who had the sense to make a cooperation deal with the government himself rather than through Private Services) – have signed plea deals. And it’s a fair prediction the inmates’ families will never recover a dime.

Miami Herald, Conning the convicts: trio admits to ripping off South Florida inmates (Apr. 3, 2017)

United States v. Warrick, Case No. 1:17-cr-20194 (S.D. Fla.)

– Thomas L. Root

In Manrique v. United States, a defendant had an initial restitution judgment entered against him that had no amount specified, the district court holding that restitution was mandatory but deferring determination of the amount until later. Marcelo Manrique filed a notice of appeal from the initial judgment. Months later, the district court entered an amended judgment, ordering the defendant to pay $4,500 restitution to one of the victims. He did not file a second notice of appeal from the amended judgment. When Marcelo nonetheless challenged the restitution amount before the 11th Circuit, the government argued that he had forfeited his right to do so by failing to file a second notice of appeal. The Circuit agreed, holding the defendant could not challenge the restitution amount.

In Manrique v. United States, a defendant had an initial restitution judgment entered against him that had no amount specified, the district court holding that restitution was mandatory but deferring determination of the amount until later. Marcelo Manrique filed a notice of appeal from the initial judgment. Months later, the district court entered an amended judgment, ordering the defendant to pay $4,500 restitution to one of the victims. He did not file a second notice of appeal from the amended judgment. When Marcelo nonetheless challenged the restitution amount before the 11th Circuit, the government argued that he had forfeited his right to do so by failing to file a second notice of appeal. The Circuit agreed, holding the defendant could not challenge the restitution amount. Today, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed. The high court said Colorado cannot retain their money simply because convictions were in place when the funds were taken from them. Once the convictions were erased, the presumption of innocence was restored. Colorado may not presume a person who is adjudged guilty of no crime, nonetheless remains guilty enough for monetary penalties. The Exoneration Act “creates an unacceptable risk of the erroneous deprivation of defendants’ property.”

Today, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed. The high court said Colorado cannot retain their money simply because convictions were in place when the funds were taken from them. Once the convictions were erased, the presumption of innocence was restored. Colorado may not presume a person who is adjudged guilty of no crime, nonetheless remains guilty enough for monetary penalties. The Exoneration Act “creates an unacceptable risk of the erroneous deprivation of defendants’ property.”

Glen filed a petition under

Glen filed a petition under