We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues. Today, we feature a number of short reports we included in our newsletter this week, but have not posted on the Web.

DOES IT SEEM LIKE THERE’RE FEWER PEOPLE ARE AROUND THE JOINT?

Fewer federal prosecutions and lighter drug sentences over the past few years has resulted in a 14% drop in the BOP prison population, according to statistics from the U.S. Courts, the Sentencing Commission and the Federal Bureau of Prisons released last week.

BOP population fell from a peak of 219,300 inmates in 2013 to 188,800 in April 2017. The decrease reflects a dramatic shift in federal policies away from stiff penalties for drug trafficking offenses in recent years. As a result, BOP facilities overcrowding has fallen from 37% to 13%.

BOP population fell from a peak of 219,300 inmates in 2013 to 188,800 in April 2017. The decrease reflects a dramatic shift in federal policies away from stiff penalties for drug trafficking offenses in recent years. As a result, BOP facilities overcrowding has fallen from 37% to 13%.

Because drug crimes account for nearly a third of all federal prosecutions, changes in drug sentences over the past decade have had a substantial impact on BOP numbers.

Administrative Office of U.S. Courts, Policy Shifts Reduce Federal Prison Population (Apr. 25, 2017)

DOJ APPOINTS SCIENTIFIC FOX TO GUARD HENHOUSE

DOJ APPOINTS SCIENTIFIC FOX TO GUARD HENHOUSE

Attorney General Jeffrey Sessions pulled the plug on the National Commission on Forensic Science, a group formed to improve forensic science and expert testimony in criminal cases, early last month.

For years, scientists and defense attorneys have fought an uphill battle to bring scientific rigor to expert testimony and analyses regularly used in courtrooms — such evidence as bite marks, hair, and bullet striations — to convict defendants. The generally accepted “bite mark” science was recently found to be phony, and other methods, including fingerprint analysis, have been criticized as being less rigorous and more subjective than AUSAs, expert witnesses, and popular culture let on.

For years, scientists and defense attorneys have fought an uphill battle to bring scientific rigor to expert testimony and analyses regularly used in courtrooms — such evidence as bite marks, hair, and bullet striations — to convict defendants. The generally accepted “bite mark” science was recently found to be phony, and other methods, including fingerprint analysis, have been criticized as being less rigorous and more subjective than AUSAs, expert witnesses, and popular culture let on.

A 2015 FBI review of 268 trial transcripts in which microscopic hair analysis was used to incriminate a defendant found bureau experts submitted scientifically invalid testimony 95% of the time. No court has banned bite mark evidence despite a consensus among scientists that the discipline is not objective.

Until Sessions disbanded it, the NCFS was the most important group pushing forensics in the direction of science.

A new Justice Department Task Force on Crime Reduction and Public Safety, set up by presidential order three months ago to “support law enforcement” and “restore public safety,” will now oversee forensic science.

Mother Jones, Jeff Sessions wants courts to rely less on science and more on “science” (Apr. 24, 2017)

MATHIS DOESN’T CARE IF YOU LIVE IN YOUR CAR

MATHIS DOESN’T CARE IF YOU LIVE IN YOUR CAR

The 8th Circuit last week ruled that the Arkansas residential burglary statute (Ark. Code Ann. Sec. 5-39-201(a)(1)) does not count as generic burglary, and therefore is not a predicate offense for sentencing under the Armed Career Criminal Act. Arkansas law defines a “residential occupiable structure” to include a vehicle, building, or other structure in which any person lives or is customarily used for overnight accommodations.

The Circuit said that under United States v. Mathis, “vehicle, building or other structure” described means and not elements. The Circuits are split 2-2 so far on the question of whether a vehicle used as living space falls under generic burglary, but the 8th Circuit said “without question, the statute, viewed as a whole, encompasses a broader range of conduct than generic burglary…” Thus, the burglary does not count for ACCA purposes.

The Circuit said that under United States v. Mathis, “vehicle, building or other structure” described means and not elements. The Circuits are split 2-2 so far on the question of whether a vehicle used as living space falls under generic burglary, but the 8th Circuit said “without question, the statute, viewed as a whole, encompasses a broader range of conduct than generic burglary…” Thus, the burglary does not count for ACCA purposes.

United States v. Sims, Case No. 16-1233 (8th Cir. Apr. 27, 2017)

3RD CIRCUIT AGREES IT HAS JURISDICTION TO REVIEW 3582 DENIALS

3RD CIRCUIT AGREES IT HAS JURISDICTION TO REVIEW 3582 DENIALS

The 6th Circuit, which held in 2010 that it has no jurisdiction to review a district judge’s refusal to lower the sentence of a prisoner who is eligible for a reduction under 18 USC 3582(c)(2), just got a little lonelier last week, as the 3rd Circuit followed the lead four other circuits in holding it has jurisdiction to review whether a district court’s refusal to reduce an eligible sentence under the statute is substantively reasonable.

Jose Rodriguez qualified for a 2-level reduction of sentence, but his district judge held Jose’s threat to public safety and post-sentencing conduct – due to the “vast drug trafficking conspiracy and a series of violent, armed robberies” in which he had engaged – were reasons to deny any reduction. The government argued the 3rd Circuit had no jurisdiction to review the district court’s decision, but the Circuit held that under 28 USC 1291 and 18 USC 3742, it always had jurisdiction to review the substantive reasonableness of a 3582(c)(2) sentence reduction decision.

Jose Rodriguez qualified for a 2-level reduction of sentence, but his district judge held Jose’s threat to public safety and post-sentencing conduct – due to the “vast drug trafficking conspiracy and a series of violent, armed robberies” in which he had engaged – were reasons to deny any reduction. The government argued the 3rd Circuit had no jurisdiction to review the district court’s decision, but the Circuit held that under 28 USC 1291 and 18 USC 3742, it always had jurisdiction to review the substantive reasonableness of a 3582(c)(2) sentence reduction decision.

Back in 2010, the 6th Circuit held that as long as a district court found the prisoner eligible for a sentence reduction, a court of appeals had no jurisdiction to review the district judge’s decision as to whether the prisoner should get the whole, a part, or none of the reduction. Since the 6th Circuit decision, the 7th, 8th, 9th and 10th Circuits have gone the other way, and last week the 3rd Circuit joined.

The decision did not help Jose much. Reviewing the sentence, the Circuit held the district judge’s refusal to give him even as much as a month off on his sentence was substantively reasonable.

United States v. Rodriguez, Case No. 16-3232 (Apr. 28, 2017)

4th CIRCUIT CLEARS WAY FOR INMATE’S RETALIATION LAWSUIT

4th CIRCUIT CLEARS WAY FOR INMATE’S RETALIATION LAWSUIT

A major hurdle inmates have to clear in bringing lawsuits for constitutional rights violations is to show that the prison officials they sue do not have qualified immunity. Unless the inmate can show that the officials violated a clearly established constitutional right, the Bivens action or 42 USC 1983 action gets tossed out.

A lot of what you might think is clearly established is not. That’s why the 4th Circuit’s decision last week was a breath of fresh air.

Pat Booker, an inmate in a South Carolina prison, filed a grievance objected to the prison’s tampering with his legal mail, and said he intended to pursue civil and criminal remedies if he found his mail meddled with again. The head of the mailroom wrote a disciplinary report on Booker saying he had threatened her. At Booker’s disciplinary hearing, he was found not guilty because he had made “legal threats” against the employee, not physical threats.

Pat sued under 42 USC 1983, arguing the employee had retaliated against him for his exercising his 1st Amendment rights. The district court dismissed, holding the prison employee was protected by qualified immunity, because a “prison inmate’s free speech right to submit internal grievances” was not clearly established by the U.S. Supreme Court of the United States, the 4th Circuit or the South Carolina Supreme Court.

The Circuit reversed, saying it had long held that prison officials may not retaliate against prisoners for exercising their right to access the courts, and “given the close relationship between an inmate filing a grievance and filing a lawsuit — indeed, the former is generally a prerequisite for the latter — our jurisprudence provided a strong signal that officials may not retaliate against inmates for filing grievances.” Seven other circuits have a recognized in published decisions that inmates possess a right, grounded in the First Amendment’s Petition Clause, to be free from retaliation in response to filing a prison grievance.

“Given the decisions from nearly every court of appeals,” the 4th said, “we are compelled to conclude that Booker’s right to file a prison grievance free from retaliation was clearly established under the First Amendment. Consistent with fundamental constitutional principles and common sense, these courts have had little difficulty concluding that prison officials violate the First Amendment by retaliating against inmates for filing grievances.”

Booker v. South Carolina Department Of Corrections, Case No. 15-7679 (4th Cir. Apr. 28, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

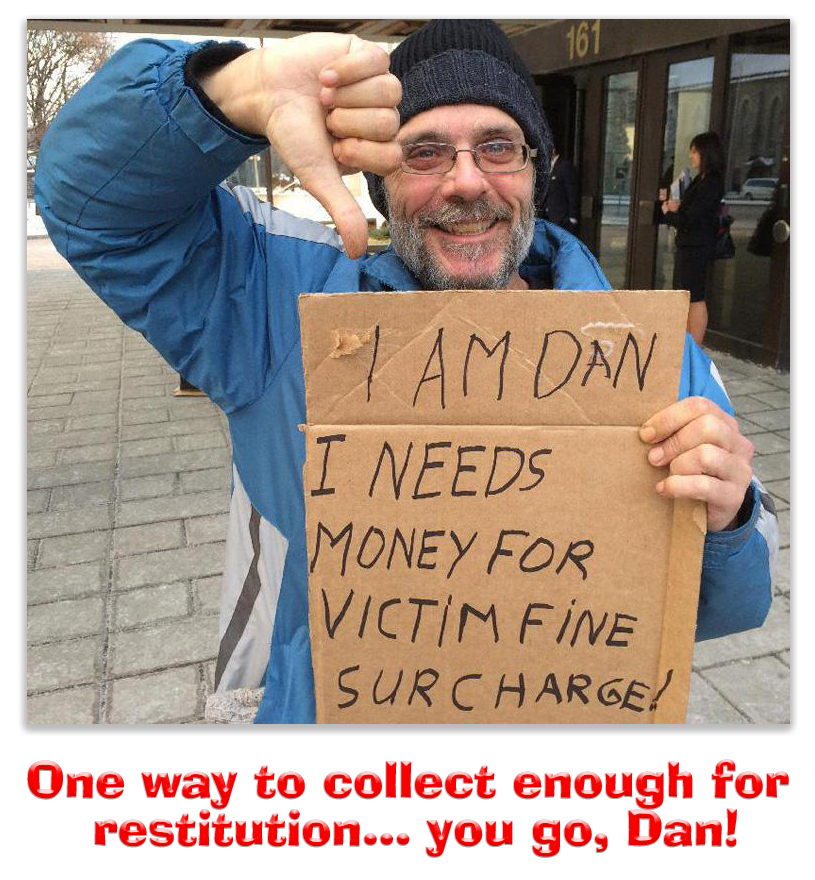

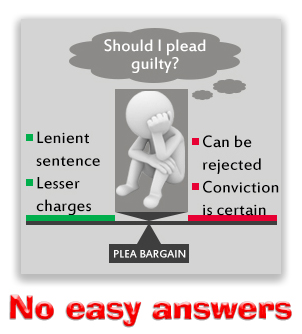

Unlike most changes in the Guidelines, the Sentencing Commission made the 2-level reduction retroactive to people already sentenced. Retroactivity under the Guidelines is not an automatic thing: a defendant must petition his or her sentencing court under 18 USC 3582(c)(2) for a sentence reduction pursuant to the retroactive Guideline. If eligible, an inmate still must convince the court that a reduction of his or her sentence ought to be awarded. Sentencing courts have wide discretion as to what to do with a sentence reduction motion, and district court decisions are nearly bulletproof.

Unlike most changes in the Guidelines, the Sentencing Commission made the 2-level reduction retroactive to people already sentenced. Retroactivity under the Guidelines is not an automatic thing: a defendant must petition his or her sentencing court under 18 USC 3582(c)(2) for a sentence reduction pursuant to the retroactive Guideline. If eligible, an inmate still must convince the court that a reduction of his or her sentence ought to be awarded. Sentencing courts have wide discretion as to what to do with a sentence reduction motion, and district court decisions are nearly bulletproof. Actually the odds for defendants were even better than that: 24% of the people who applied were not even eligible for the reduction, for reasons ranging from not having been sentenced under the drug guidelines to being locked in place by statutory mandatory minimum sentence. Only 8% of the 46,000 were denied on the merits (although due to sloppy district court records, the number could have been as high as 13%).

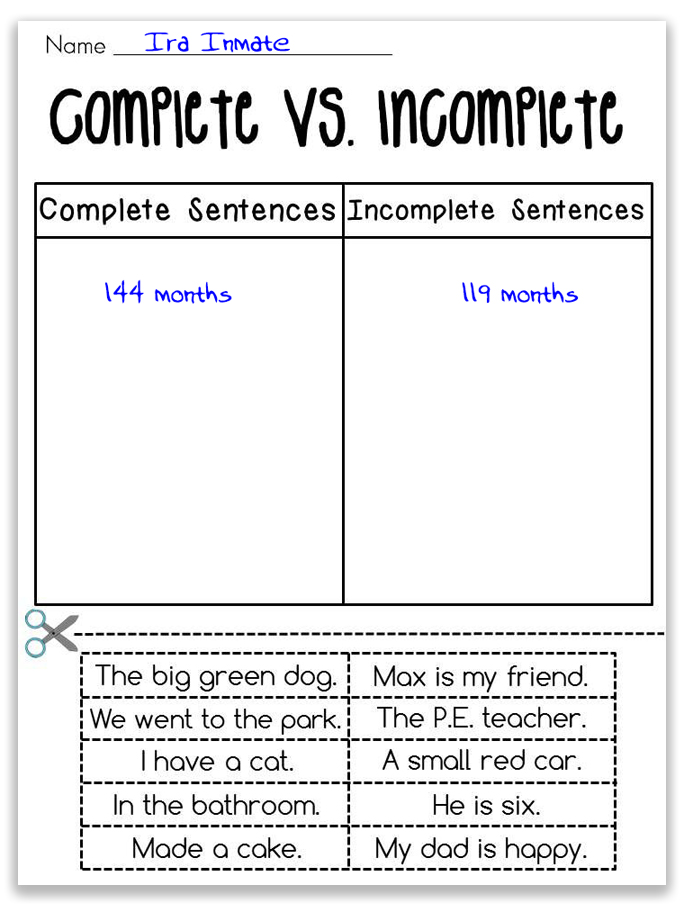

Actually the odds for defendants were even better than that: 24% of the people who applied were not even eligible for the reduction, for reasons ranging from not having been sentenced under the drug guidelines to being locked in place by statutory mandatory minimum sentence. Only 8% of the 46,000 were denied on the merits (although due to sloppy district court records, the number could have been as high as 13%). The average sentence was cut from 144 to 119 months, a 17% reduction. Of those receiving sentence reductions, 32% were convicted for methamphetamines, 28% for powder cocaine, 20% for crack, 9% for pot and 7% for heroin. The racial and ethnic distribution was 30% white, 33% black, and 41% Hispanic. Curiously enough, the defendant’s criminal history seemed to have no effect on likelihood of receiving a sentence cut, with novices and pros alike getting cuts at about the same rate.

The average sentence was cut from 144 to 119 months, a 17% reduction. Of those receiving sentence reductions, 32% were convicted for methamphetamines, 28% for powder cocaine, 20% for crack, 9% for pot and 7% for heroin. The racial and ethnic distribution was 30% white, 33% black, and 41% Hispanic. Curiously enough, the defendant’s criminal history seemed to have no effect on likelihood of receiving a sentence cut, with novices and pros alike getting cuts at about the same rate.