We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

BECAUSE I SAID SO

Many of us vowed that when we became parents, we would never dismiss our kids’ demand for an explanation with the peremptory ipse dixit “because I said so.” And just as many of us kept that promise only until our children began to talk.

There was a time when a judge only had a statutory sentencing range, and could sentence anywhere within the range on any whim he or she had. The judge could slap someone with 10 years, and the heavy lifting of figuring out where within that 10-year period the prisoner was released fell to the Parole Commission.

There was a time when a judge only had a statutory sentencing range, and could sentence anywhere within the range on any whim he or she had. The judge could slap someone with 10 years, and the heavy lifting of figuring out where within that 10-year period the prisoner was released fell to the Parole Commission.

The Sentencing Guidelines, now approaching 30 years of age, changed all of that. The judge now did all the work, assigning a criminal history score to the defendant, determining the total offense level in points, and then using a matrix to determine a sentencing range. The range – much narrower that the statutory punishment specified in the U.S. Code – left the court with scant discretion. A crime might carry a 0-10 year statutory sentencing range, but the Guidelines gave the court a sentencing range of 71-87 months.

With the district court’s greater involvement in the sentencing calculus came greater demands that the district court do more than just impose a sentence without an explanation, the “because I say so” approach. After United States v. Booker made the Guidelines “advisory” – giving back to the judges some of the discretion the Guidelines had originally taken away – a collection of Supreme Court cases laid down the requirements that sentences be “procedurally reasonable” (that the Guidelines be calculated accurately) and that they likewise be “substantively reasonable,” in other words, not appear to be too unfair.

Because courts of appeal cannot review a sentence for reasonableness without knowing why the district court decided on the sentence it imposed, appellate courts imposed on trial judges the responsibility to explain their sentencing decisions rather than imposing a sentence simply because the judge says so.

Mark Wireman, a serial kiddie porn offender, had a sentencing range of 210-262 months, due to his lengthy criminal history, and to the child porn Guidelines, which pile on enhancements for number of images stored, for use of a computer, and a host of other offense attributes that apply in virtually every kid porn offense. There is little doubt that society finds child pornography odious. Congress certainly finds it an issue that draws lawmakers of both parties into a group hug and chorus of “kumbaya,” followed by unanimously-passed legislation in which each legislator tries to out-tough the other in being harsh on kiddie porn.

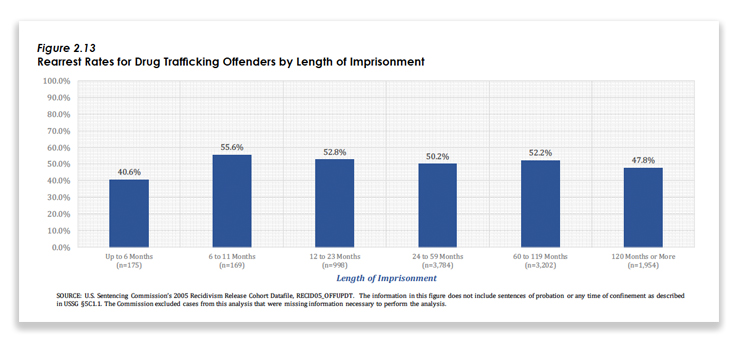

As a result, most of the child porn Guidelines were written not after a reasoned consideration of data but because Congress, in a bipartisan tough-on-porn frenzy, dictated how it should read. More than one court has complained that it should have to pay deference to the Draconian sentences recommended by the child-porn Guidelines, because those Guidelines were not data-driven.

Mark was lucky enough to have a team of public defenders representing him. As a group, federal public defenders deliver spirited and experienced representation seldom seen in retained counsel until one gets to blue-chip law firms. Mark’s defenders wrote a top-drawer sentencing memorandum that the policy underlying the child porn Guidelines was flawed:

First, that § 2G2.2(a)(2)’s base offense level of 22 is “harsher than necessary” under the 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a) sentencing factors; second, that courts should be hesitant to rely on § 2G2.2 because the Sentencing Commission did not depend on empirical data when drafting § 2G2.2; and third, that the Specific Offense Characteristics outlined in § 2G2.2 are utilized so often ‘that they apply in nearly every child-pornography case’ and therefore fail to distinguish between various offenders.

Mark also that his own circumstances – including a traumatizing childhood where he was repeatedly sexually abused by family members and the fact that in this case he shared a relatively small amount of child pornography with only one other – of warranted a downward variance from this excessive guideline range.

The sentencing court said, “Frankly, I’m struggling with a lot of the issues that have been raised in… Defendant’s counsel’s memorandum…” but made no further reference to the filing. Ultimately, the court, concerned with the risk that Mark would keep committing the same or similar offenses, sentenced him within the advisory Guidelines range to 240 months.

This week, the 10th Circuit affirmed the sentence, rejecting Mark’s complaints that the district court ignored his counsel’s sentencing memorandum. Specifically, Mark argued that where the defendant attacked the Guidelines on policy grounds – an attack becoming increasingly common in child sex cases – a district court is obligated to address the claim.

The 10th disagreed, nothing that while “a district court must explain its reasons for rejecting a defendant’s nonfrivolous arguments for a more lenient sentence,” and while a district court may even “vary from the Sentencing Guidelines based on a policy disagreement with those Guidelines,” the manner in which a district court must explain its reasons for rejecting a defendant’s arguments is not “set in stone across all cases.” Where, as in this case, “the district court has imposed a sentence within the Guidelines, our cases have noted that the district court need not specifically address and reject each of the defendant’s arguments for leniency so long as the court somehow indicates that it did not rest on the guidelines alone, but considered whether the guideline sentence actually conforms, in the circumstances, to the 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a) statutory factors.”

The 10th disagreed, nothing that while “a district court must explain its reasons for rejecting a defendant’s nonfrivolous arguments for a more lenient sentence,” and while a district court may even “vary from the Sentencing Guidelines based on a policy disagreement with those Guidelines,” the manner in which a district court must explain its reasons for rejecting a defendant’s arguments is not “set in stone across all cases.” Where, as in this case, “the district court has imposed a sentence within the Guidelines, our cases have noted that the district court need not specifically address and reject each of the defendant’s arguments for leniency so long as the court somehow indicates that it did not rest on the guidelines alone, but considered whether the guideline sentence actually conforms, in the circumstances, to the 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a) statutory factors.”

The Circuit said it was “not persuaded that the principle we note… that a district court need not specifically address and instead may functionally reject a defendant’s arguments for leniency when it sentences him within the Guidelines range — should differ just because the defendant critiques the applicable Guideline itself on policy grounds, as Defendant does in the case before us today. In our circuit, a within- guideline-range sentence that the district court properly calculated… is entitled to a rebuttable presumption of reasonableness on appeal… We would be disregarding the spirit of this appellate presumption if we were to require the district court to defend § 2G2.2 or any other Guideline that leads to such a presumptively reasonable sentence.”

United States v. Wireman, Case No. 15-3291 (10th Circuit, Feb. 28, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root