We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

I INSTRUCT THE JURY TO DISREGARD THE SMELL

There’s an old saying among trial attorneys that goes something like for the judge to instruct the jury to disregard something very prejudicial it has just seen or heard is “like throwing a skunk into the jury box and then telling the jury to disregard the smell.”

The smell in a decision from the 7th Circuit earlier this week was just too intense. What makes the case even more noteworthy is that the trial judge who crossed the line was not just some small-town hack put on the bench as a reward for political loyalty, but rather Circuit Judge Richard Posner, arguably the 7th Circuit’s MVP for the past 25 years.

The smell in a decision from the 7th Circuit earlier this week was just too intense. What makes the case even more noteworthy is that the trial judge who crossed the line was not just some small-town hack put on the bench as a reward for political loyalty, but rather Circuit Judge Richard Posner, arguably the 7th Circuit’s MVP for the past 25 years.

Judge Posner was taking a turn in the trenches, as circuit judges do from time to time, just to experience some of the rough-and-tumble which they are called upon to referee up on the appellate bench. The plaintiff was Hakeem El-Bey, a self-described Moorish national, who was running the usual tax scam in which he set up an eponymous trust, naming himself as the trustee and fiduciary, and then claimed $300,000 refunds from the IRS. (There are finer points to the scheme, but we’ll leave them out, because they might just encourage illegality).

The IRS resisted his demands, but someone at the Service finally pushed the wrong button, and a check for $300,000 got sent to Hakeem, who quickly spent it. The blunder happened again a few months later, and Hakeem figured he was on Easy Street.

Alas, it was not to be. The IRS Criminal Division caught up with him, and in short order Hakeem was indicted for mail fraud and making false claims to the IRS.

Hakeem represented himself at trial, an idea the foolishness of which we probably do not have to explain. Judge Posner permitted Hakeem his blunder, but appointed a standby attorney, Gabriel A. Fuentes.

Hakeem followed the tax protester/sovereign citizen script to the letter, filing pretrial motions related to admiralty law, the Uniform Commercial Code, and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Judge Posner excluded Hakeem’s sovereign citizen evidence, and warned Hakeem that if he brought it up, the judge might exclude him from the courtroom, too, and let attorney Fuentes carry the defense load/

Hakeem followed the tax protester/sovereign citizen script to the letter, filing pretrial motions related to admiralty law, the Uniform Commercial Code, and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Judge Posner excluded Hakeem’s sovereign citizen evidence, and warned Hakeem that if he brought it up, the judge might exclude him from the courtroom, too, and let attorney Fuentes carry the defense load/

Some background here: the IRS likes to say it depends on voluntary compliance with the tax laws. And of course it does, just like the state police depend on voluntary compliance with the traffic laws. There’re just not enough cops to stop everyone. But Hakeem and his fellow tax protest travelers like to argue that “voluntary compliance” means taxpayers send in their checks and returns out of the goodness of their hearts. The argument has more holes than a swiss cheese factory, but that inconvenient fact does not deter the Hakeems of the world.

At trial, Hakeem cross-examined an IRS representative on the matter, asking her whether federal tax law compliance was voluntary. She responded:

The tax laws are based on individuals taking their information, voluntarily putting them on the tax returns, and mailing them to the IRS. However, the law states if you don’t do that the IRS can come in and file for you because the law states you file and pay your income tax.

Hakeem figured this was his “A-ha!” moment. He argued with the witness that “you just contradicted yourself. Because in one case you are saying that the IRS is saying filing taxes is voluntary compliance?” At this point, Judge Posner had had his fill:

Hakeem figured this was his “A-ha!” moment. He argued with the witness that “you just contradicted yourself. Because in one case you are saying that the IRS is saying filing taxes is voluntary compliance?” At this point, Judge Posner had had his fill:

THE COURT: Look, paying taxes is not voluntary.

THE DEFENDANT: That’s what it says here. I’m not saying it.

THE COURT: Come on.

THE DEFENDANT: Judge, I’m not saying it.

THE COURT: You don’t pay your tax, you go to jail.

THE DEFENDANT: Judge, I’m just saying what they are saying what they have—

THE COURT: Payment of taxes to the government is not voluntary.

THE DEFENDANT: Okay. Judge, so you brought in from behind the law.

THE COURT: Just—look, I’m going to kick you out if you keep on with this nonsense. You understand that? You can go watch the case from another room.

THE DEFENDANT: Okay. I am through.

THE COURT: Don’t you say that tax payment is voluntary.

The jury heard it all.

The government, with one eye on an appeal, was concerned. The next day, before the jury entered the courtroom, the AUSA told the judge “that some of what happened yesterday may have been potentially prejudicial to the defendant … importantly, perhaps, [it] has left a misimpression with the jury in certain respects.” Judge P agreed, and instructed the jury that it should ignore the malodorous exchange of the day before:

After the jury entered the courtroom, the court explained, “You don’t have to worry about the exchanges that Mr. El-Bey and I have had. And I don’t want you to feel any hostility to Mr. El-Bey just because I got annoyed occasionally.” He then proceeded to read parts of the transcript of the previous day’s exchange back to the jury, including his exchange with Hakeem on “voluntary compliance.” The judge concluded

When I said: If you don’t pay taxes you go to jail, what I was simply saying was you must pay taxes, and if you don’t pay taxes it’s criminal and you can be sent to jail. I was not talking about Mr. El-Bey, because he isn’t charged with tax evasion.

Unfortunately, the judge was not quite done. When he was reading the jury instructions, Judge Posner went off-script, ignoring the written instruction on materiality, and ad libbing instead:

One [element] is that … the scheme to defraud involved a materially false or fraudulent pre-tense, representation, or promise. That’s very important, that notion of materiality… Little white lies, those are not material falsehoods. They don’t—I mean, they may embarrass you when it’s discovered, but they’re not—that’s not wrongful conduct. It’s when, with specific reference to our case, if you—if tell—if you tell the Internal Revenue Service a lie which is capable of getting them to do something which they would never do if they knew the truth, namely, give you $300,000 to which you’re not entitled, that is a material falsehood. That’s fraud. And that is an element of the charges.

On appeal, Hakeem complained that Judge Posner had been biased against him, and thus violated his due process right to a fair trial. In the 7th Circuit, that’s like accusing Taylor Swift of lip-syncing. But the 7th had to reluctantly that Hakeem had a point:

On appeal, Hakeem complained that Judge Posner had been biased against him, and thus violated his due process right to a fair trial. In the 7th Circuit, that’s like accusing Taylor Swift of lip-syncing. But the 7th had to reluctantly that Hakeem had a point:

It is clear from the transcript of the trial court proceedings that El-Bey was a difficult litigant. He filed numerous irrelevant motions, disregarded court instructions, and often inappropriately interrupted the district court to express disagreement and dissatisfaction. Nonetheless, we agree with El-Bey that the district court’s remarks during cross-examination of the government’s first witness conveyed bias regarding his dishonesty or guilt. The district court interrupted El-Bey at the beginning of his cross-examination, stating, “Look, paying taxes is not voluntary.” When El-Bey noted that he was only reading what the document stated, the district court remarked “Come on”—a statement laced with skepticism. The district court continued with further remarks in the presence of the jury reflecting upon El-Bey’s dishonesty or guilt, stat-ing, “You don’t pay your tax, you go to jail,” and “I’m going to kick you out if you keep on with this nonsense…” The purpose of the comments cannot eliminate the bias conveyed to the jury by the remarks here. The court’s statements that one who does not pay taxes goes to jail and that El-Bey was acting in a nonsensical manner indicated bias about El-Bey’s guilt or honesty to the jury.

And if that were not enough, the Circuit said, Judge Posner did it again when he ad libbed instructions that “conveyed to the jury that El-Bey was guilty by concluding that El-Bey’s receipt of the checks and money made him guilty of mail fraud and making false claims.”

The appellate court had no doubt about Hakeem’s culpability, noting that “there is more than enough evidence of El-Bey’s guilt. But in the end, that did not matter. “We must… conclude that the unfairness in the trial requires reversal,” the court said. “Any other holding would constitute the adoption of the principle that a defendant the court thinks is obviously guilty is not entitled to a fair trial.”

Hakeem will be retried. Judge Posner will probably not be there.

United States v. El-Bey, Case No. 15-3180 (7th Circuit, October 24, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

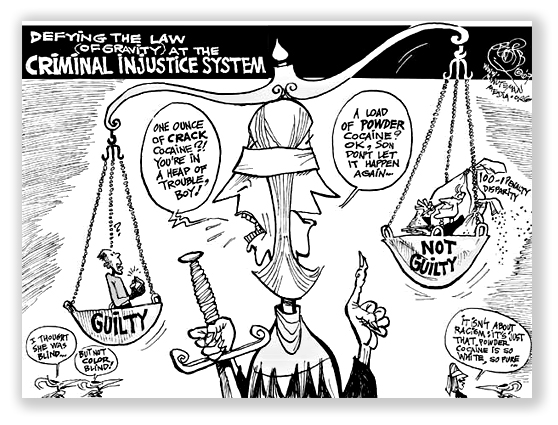

Richard Zayas, ATF agent and professional “stash house sting” promoter (with more than 100 to his credit) took his show on the road to Cleveland, where he was again successful in finding young, poor black defendants to recruit into his fictitious robbery ring.

Richard Zayas, ATF agent and professional “stash house sting” promoter (with more than 100 to his credit) took his show on the road to Cleveland, where he was again successful in finding young, poor black defendants to recruit into his fictitious robbery ring. Last week, the 6th Circuit upheld the convictions. The Court noted that while some circuits said that under the outrageous government conduct defense, government involvement in a crime may be “so excessive that it violates due process and requires the dismissal of charges against a defendant even if the defendant was not entrapped,” the 6th Circuit had not previously held that the government could be so outrageous as to bar prosecution, and it was not going to do so here.

Last week, the 6th Circuit upheld the convictions. The Court noted that while some circuits said that under the outrageous government conduct defense, government involvement in a crime may be “so excessive that it violates due process and requires the dismissal of charges against a defendant even if the defendant was not entrapped,” the 6th Circuit had not previously held that the government could be so outrageous as to bar prosecution, and it was not going to do so here.