We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

HOUSE PASSES EQUAL ACT

Over 25 years ago, the United States Sentencing Commission – never a hotbed of progressive thought – concluded that the draconian drug policy of considering every gram of crack cocaine to be the equivalent to 100 grams of powder cocaine was irrational and resulted in disproportionately severe crack sentences being imposed mostly on black defendants.

Over 25 years ago, the United States Sentencing Commission – never a hotbed of progressive thought – concluded that the draconian drug policy of considering every gram of crack cocaine to be the equivalent to 100 grams of powder cocaine was irrational and resulted in disproportionately severe crack sentences being imposed mostly on black defendants.

But just as sex sells in the marketing ethos, outrageous punishment sells in the political world. At least until a few years ago, no member of Congress ever lost an election because he or she was too tough on crime.

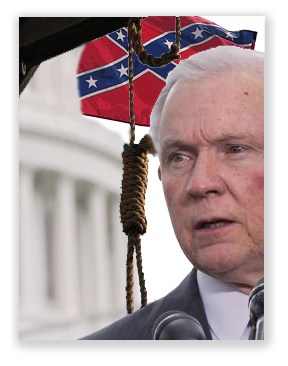

Fourteen years ago, Presidential candidate Barack Obama decried the crack-to-powder disparity, and in April 2009, his Dept of Justice lobbied for the elimination of the 100:1 ratio. The House passed a 1:1 bill that year, but by the time the Senate took it up the following summer, 1:1 had become 18:1 in order to satisfy certain troglodytes in that chamber, chief among them the unlamented former senator Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III of Alabama.

The resulting Fair Sentencing Act mandated a new 18:1 crack/powder quantity disparity ratio, but without retroactivity, so that accidents of time hammered a defendant who was sentenced in July 2010, for example, with a 100:1 sentence, while one whose lawyer managed to delay sentencing until the dog days of August benefitted from a much shorter mandatory minimum. Under this formula, people caught with 28 grams of crack receive the same sentence as someone caught with 500 grams of powder cocaine, despite the American Medical Association’s findings that there is no chemical difference between the two substances.

The Fair Sentencing Act became retroactive to all defendants with crack mandatory minimums (but see United States v. Terry) by the passage of the First Step Act in December 2018.

Fast forward to last week. The EQUAL Act, pending in both houses of Congress, proposes the elimination of any disparity between crack and powder cocaine. But Sen Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) a conservative lawmaker from the heart of the corn belt but a champion of criminal justice reform, said candidly that he didn’t think he could find enough Republican votes to come up with the 60 needed to pass the EQUAL Act in the Senate.

This past Tuesday, the House decided to give Grassley the chance to try anyway, passing the EQUAL Act (H.R. 1693) by a lopsided vote of 361-66. (Grassley may have a point. All 66 nay votes in the House were from GOP lawmakers).

Surprisingly (at least to me), Representative Louie Gohmert (R-Texas), a former judge who has said some people – not without some justification, I might add – think he is the “dumbest guy in Congress,” was a sponsor of the EQUAL Act. The Congressman said the measure was “a great start toward getting the right thing done. He said during floor debate that as a judge, “Something I thought Texas did right was [to] have an up-to-12 months substance abuse felony punishment facility. Some thought it was strange that a strong conservative like myself used that as much as I did. But I saw this is so addictive, it needs a length of time to help people to change their lives for such a time that they’ve got a better chance of making it out, understanding just how addictive those substances are.”

In the Senate, at least 10 Republicans would have to join with all Democrats to advance it in the evenly divided chamber. A Senate version of the EQUAL Act, S.79, was introduced by Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and currently has five cosponsors, including three Republicans: Sen. Rob Portman (Ohio), Rand Paul (Kentucky), and Thom Tillis (NC). It remains before the Committee on the Judiciary.

The House version of the EQUAL Act that just passed provides that in the case of a defendant already serving a sentence based in any part on cocaine base may return to court to receive a sentence reduction, in a procedure that appears to be similar to the Section 404 procedure for Fair Sentencing Act retroactive resentencings, but with one interesting twist: Section 404 proceedings do not require the district judge to consider whether a sentence reduction is consistent with the sentencing factors in 18 USC § 3553(a). The EQUAL Act procedure permits imposition of a sentence reduction only “after considering the factors set forth in section 3553(a) of title 18, United States Code.”

Is this a good thing? Probably anything that adds structure (however slight) to the process is beneficial. Without any standard, nothing prevents a district judge from making arbitrary decisions. Even with a § 3553(a) requirement, a Sentencing Commission study of the compassionate release process has found that a defendant’s likelihood of success ranged from about 70% in Oregon to a lousy 1.5% (Western District of North Carolina).

Anything that can avoid swapping one disparity for another is probably a good thing.

Anything that can avoid swapping one disparity for another is probably a good thing.

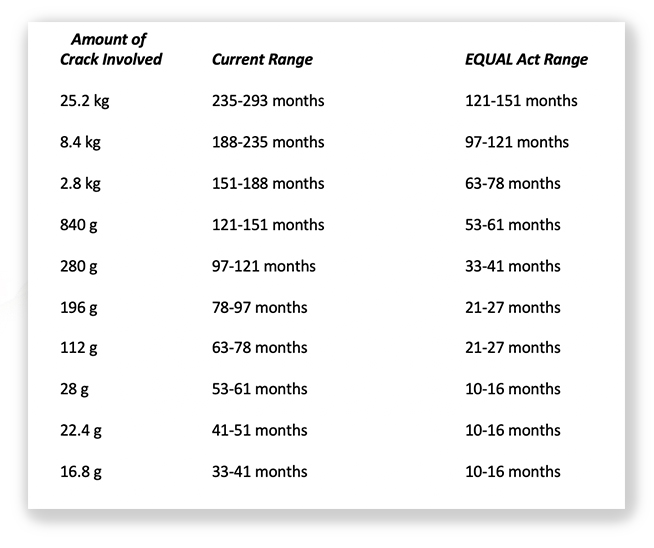

So what would be the practical effect of such a change? When the Fair Sentencing Act passed, the U.S. Sentencing Commission responded by reducing sentencing ranges across the board for crack offenses, so that a five-year mandatory sentence for a defendant without a prior criminal history possessing 28 grams of crack equaled what the Guidelines said his sentence should be. If the ratio falls to 1:1, and if the Sentencing Commission makes the same adjustments, a hypothetical defendant with no prior record (and no sentencing enhancements) would see the following sentencing range adjustments:

Of course, as they say in the commercials, “actual results may vary.” But if the courts are mandated to consider § 3553(a) first, maybe they will vary less.

But first, the EQUAL Act has to pass the Senate…

– Thomas L. Root