We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

DISTRICT COURT HOLDS SEX OFFENDER INTERNET REPORTING LAW UNCONSTITUTIONAL

In the pantheon of criminal offenses, none feels seamier or more disgusting than sex offenses. The label covers crimes from groping to rape to possessing child porn, with the offenders routinely not just given long prison sentences but subjected to limitations during and after prison that drug offenders, fraudsters and robbers never experience.

In the pantheon of criminal offenses, none feels seamier or more disgusting than sex offenses. The label covers crimes from groping to rape to possessing child porn, with the offenders routinely not just given long prison sentences but subjected to limitations during and after prison that drug offenders, fraudsters and robbers never experience.

A rudderless young man who robbed a couple of banks and served over a decade in federal prison turned a talent as a “jailhouse lawyer” into a law school degree and admission to the bar. He’s now a celebrated law school professor and was even the subject of a laudatory 60 Minutes story. And he deserves it.

But what if, instead of armed bank robbery, the inmate had downloaded images of naked children engaged in simulated sex. Just my opinion here, but I suspect the 60 MInutes crew would have stayed home, the State of Washington bar would never have found him to be rehabilitated, and his name would be found on the Internet – along with his address and a warning that he was a sex offender – as a warning to neighbors instead of hagiography. He’d be serving up Slurpees at 7-Eleven instead of training future lawyers at Georgetown.

Sex crimes are forever, and the “forever” is untethered to the degree of harm caused to society. Rape and sex abuse are one thing, but as disgusting as I find the idea of looking at (let alone collecting) suggestive images of naked kids, I have trouble with the idea that we can forgive a history of violence but not someone who looked at flickering images on a computer screen.

Sex crimes are forever, and the “forever” is untethered to the degree of harm caused to society. Rape and sex abuse are one thing, but as disgusting as I find the idea of looking at (let alone collecting) suggestive images of naked kids, I have trouble with the idea that we can forgive a history of violence but not someone who looked at flickering images on a computer screen.

No crime is as easy to demagogue as is a sex crime. That may be why Congress has found it so easy to rachet up minimum sentences for kiddie porn offenses. The Sentencing Commission has candidly acknowledged that at the direction of Congress, it has amended USSG § 2G2.2 several times, each time recommending harsher penalties. In United States v. Dorvee, the 2nd Circuit noted that the rachet effect persisted despite the Sentencing Commission being

openly opposed [to] these Congressionally directed changes… Speaking broadly, the Commission has also noted that “specific directives to the Commission to amend the guidelines make it difficult to gauge the effectiveness of any particular policy change, or to disentangle the influences of the Commission from those of Congress.”

There’s some evidence that the Congressional view of child porn punishment is at odds with public sentiment. US District Court Judge James Gwin of the Northern District of Ohio, as an experiment, had jurors in his courtroom anonymously note a recommended sentence for people they convicted, He would not look at the recommendations until he had imposed sentence. In one sex offender case, he wrote,

While this case and the jury selected to hear it were unremarkable, the disparity between the punishment that the jury felt [the defendant] should receive and the punishment recommended by the Guidelines was striking. The jurors’ mean recommended sentence was 20 months imprisonment, and the median recommended sentence was 15 months. The Guidelines recommended a sentence between 87 and 108 months. Even the low end of the Guidelines range was almost six times the jurors’ median recommendation.

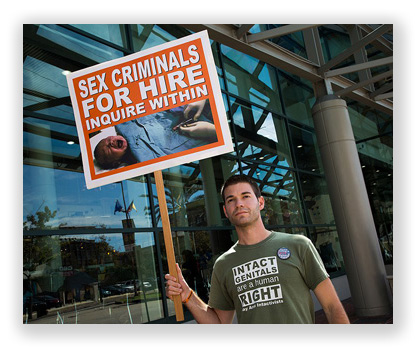

All of the foregoing gets us to today’s case. Connecticut law requires that after release, convicted sex offenders disclose to police all of their email and social media addresses, as well as other Internet communication identifiers. Jim Cornelio, a released offender, sued in federal court, claiming the disclosure requirement violated his 1st Amendment right to free speech.

Last week, the US District Court for Connecticut agreed. The Court held that by compelling Jim to disclose all of his Internet addresses and identifiers, “the law chills and inhibits his right to speak freely on the Internet and to do so anonymously if he wishes… [Thus], the State must show that the law advances an important government interest that is unrelated to the suppression of free speech. And it must also show that the law does not burden substantially more speech than necessary to further the government’s interest.”

Last week, the US District Court for Connecticut agreed. The Court held that by compelling Jim to disclose all of his Internet addresses and identifiers, “the law chills and inhibits his right to speak freely on the Internet and to do so anonymously if he wishes… [Thus], the State must show that the law advances an important government interest that is unrelated to the suppression of free speech. And it must also show that the law does not burden substantially more speech than necessary to further the government’s interest.”

The Judge held that the State “has an important government interest in detecting and deterring sex offenders from using the Internet to engage in crime.” However, although the disclosure law has been in place for over 15 years,

the State cannot point to a single example of when its database of sex offenders’ email addresses and other Internet communication identifiers has helped the police detect or solve any crimes. And the State concedes that it has no evidence that requiring sex offenders to disclose their Internet communication identifiers deters them from using the Internet to commit more crimes. Moreover, even if I assumed that the State was able to show that the disclosure law advances an important government interest, the State nonetheless fails to show that the breadth of the disclosure law does not burden substantially more speech than necessary to further that interest.

Cornelio v Connecticut, Case No 3:19-cv-1240, 2023 USDist LEXIS 163106 (D.Conn. Sep 14, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root

This is important to federal prisoners convicted of sex-related offenses by far, the largest cohort of repeat offenders among those convicted of sex offenses is created by failing in some technical respect to adhere to the often Byzantine state sex offender registration statutes. Unsurprisingly, the failure to comply with state registration statutes becomes a federal crime.

This is important to federal prisoners convicted of sex-related offenses by far, the largest cohort of repeat offenders among those convicted of sex offenses is created by failing in some technical respect to adhere to the often Byzantine state sex offender registration statutes. Unsurprisingly, the failure to comply with state registration statutes becomes a federal crime.