We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

A SHOT ACROSS THE BOW

A SHOT ACROSS THE BOW

We have to begin, as always, with our usual disclaimer: child pornography is odious. The creation of it has a terrible impact on the children forced into such conduct. And of course, we – like the overwhelming majority of people – are repulsed by child porn itself. Even reading details of it in appellate court decisions often has us getting up frequently to wash our hands.

As a result, there is hardly a crime easier to demagogue than child pornography. Congress has juiced the kiddie porn sentencing guidelines repeatedly, because – after all – who could object to hammering depraved people who looked at kiddie porn with what are effectively life sentences? Certainly not legislators. And can you imagine a senator or House member who voted against dictating guideline levels to the Sentencing Commission (who is expert in sentencing matters)? Any challenger at reelection time is going to point at the unfortunate solon and shout, “My opponent voted to let child molesters out of prison early!!!”

As a result, there is hardly a crime easier to demagogue than child pornography. Congress has juiced the kiddie porn sentencing guidelines repeatedly, because – after all – who could object to hammering depraved people who looked at kiddie porn with what are effectively life sentences? Certainly not legislators. And can you imagine a senator or House member who voted against dictating guideline levels to the Sentencing Commission (who is expert in sentencing matters)? Any challenger at reelection time is going to point at the unfortunate solon and shout, “My opponent voted to let child molesters out of prison early!!!”

It’s the kind of thing (along with eating one too many pork-chops-on-a-stick) that will keep a politician awake at night.

It’s the kind of thing (along with eating one too many pork-chops-on-a-stick) that will keep a politician awake at night.

Seven years ago, the U.S. Court of Appeals fired the first warning shot at the child porn guidelines in United States v. Dorvee. After reviewing in detail the politically-charged and commonsense-challenged history of the child pornography guideline, the Court “encouraged” district judges “to take seriously the broad discretion they possess in fashioning sentences under § 2G2.2 – ones that can range from non-custodial sentences to the statutory maximum – bearing in mind that they are dealing with an eccentric Guideline of highly unusual provenance which, unless carefully applied, can easily generate unreasonable results.”

Last Monday, the 2nd Circuit revisited the question, and in a remarkable decision – a real shot across the bow for the child pornography Guidelines – held that a child porn sentence that fell within the calculated Guidelines range was nevertheless substantively unreasonable. And it did so even where the defendant was rather unsympathetic.

Last Monday, the 2nd Circuit revisited the question, and in a remarkable decision – a real shot across the bow for the child pornography Guidelines – held that a child porn sentence that fell within the calculated Guidelines range was nevertheless substantively unreasonable. And it did so even where the defendant was rather unsympathetic.

To our knowledge, no court has ever before held that a within-range Guidelines sentence was substantively unreasonable. That alone makes today’s decision a remarkable case.

Joe Jenkins – a man with no prior criminal conduct – was on his way to Canada to meet his parents for a family vacation. When Joe crossed into Canada, Canadian customs people thought he was acting squirrely, and so they inspected his laptop and a couple of thumb drives he had with him. They found a lot of kiddie porn.

Joe was charged in Canada, but – being released on bail – he beat feet back to the US. The Mounties, deciding that getting mad was not as rewarding as getting even, asked US Homeland Security whether they might be interested in Joe’s collection. They were. Joe was charged with a count of possession of child porn, and another of transportation of such porn across state lines.

At trial, Joe was obstreperous, sharp-tongued and uncooperative. He was convicted, and the court figured his Guidelines as 210-240 months. Joe was sentenced to 120 months for possession, the statutory maximum. On the transportation count, he got a concurrent sentence of 225 months, with a supervised release term of 25 years after the sentence ended. The district court thought Joe’s disrespect for the judicial process – not to mention some of the whoppers he told on the stand – suggested he was likely to possess child porn again after he got released.

At trial, Joe was obstreperous, sharp-tongued and uncooperative. He was convicted, and the court figured his Guidelines as 210-240 months. Joe was sentenced to 120 months for possession, the statutory maximum. On the transportation count, he got a concurrent sentence of 225 months, with a supervised release term of 25 years after the sentence ended. The district court thought Joe’s disrespect for the judicial process – not to mention some of the whoppers he told on the stand – suggested he was likely to possess child porn again after he got released.

The 2nd Circuit, in an unprecedented decision, held that Joe’s “in Guidelines” sentence was excessive. Noting that “in view of Jenkins’s age [43], this sentence effectively meant that Jenkins would be incarcerated and subject to intense government scrutiny for the remainder of his life,” the Court rejected the sentence as violating § 3553(a)’s “parsimony clause,” which instructs a district court to impose a sentence “sufficient, but not greater than necessary,” to achieve § 3553(a)(2)’s goals.

The Court noted that “bringing a personal collection of child pornography across state or national borders is the most narrow and technical way to trigger the transportation provision. Whereas Jenkins’s transportation offense carried a s tatutory maximum of 20 years, the statutory maximum for his possession offense was “only” 10 years. Jenkins was eligible for an additional 10 years’ imprisonment because he was caught with his collection at the Canadian border rather than in his home.” What’s more, the Court said, the Sentencing Commission’s own statistics suggest that Joe’s age makes him much less likely to reoffend after a 10-year prison stint, which is at odds with the district judge’s holding to the contrary.

tatutory maximum of 20 years, the statutory maximum for his possession offense was “only” 10 years. Jenkins was eligible for an additional 10 years’ imprisonment because he was caught with his collection at the Canadian border rather than in his home.” What’s more, the Court said, the Sentencing Commission’s own statistics suggest that Joe’s age makes him much less likely to reoffend after a 10-year prison stint, which is at odds with the district judge’s holding to the contrary.

The Circuit reserved its most withering criticism for the enhancements that applied to Joe’s Guidelines calculations. The four most common include a 2-level increase for use of a computer and another increase for “more than 600 images.” The Court said that in Dorvee,

we noted that four of the sentencing enhancements were so “run-of-the-mill” and “all but inherent to the crime of conviction” that “[a]n ordinary first-time offender is therefore likely to qualify for a sentence of at least 168 to 210 months” based on an offense level increased from the base level of 22 to 35… The concerns we expressed in Dorvee apply with even more force here and none of them appears to have been considered by the district court. Jenkins received precisely the same “run-of-the-mill” and “all-but-inherent” enhancements that we criticized in Dorvee, resulting in an increase in his offense level from 22 to 35. These enhancements have caused Jenkins to be treated like an offender who seduced and photographed a child and distributed the photographs and worse than one who raped a child…

The Circuit cited Sentencing Commission stats showing that 96% of child porn possession defendants received the enhancement for an image of a victim under the age of 12, 85% for an image of sadistic or masochistic conduct or other forms of violence, 79% for an offense involving 600 or more images, and 95% for the use of a computer. When nearly everyone qualifies for the enhancement, it ceases being an enhancement and begins being merely a characteristic of the underlying offense.

The Circuit cited Sentencing Commission stats showing that 96% of child porn possession defendants received the enhancement for an image of a victim under the age of 12, 85% for an image of sadistic or masochistic conduct or other forms of violence, 79% for an offense involving 600 or more images, and 95% for the use of a computer. When nearly everyone qualifies for the enhancement, it ceases being an enhancement and begins being merely a characteristic of the underlying offense.

The 2-1 majority observed that

a sentence of 225 months for a first-time offender who never spoke to, much less approached or touched, a child or transmitted explicit images to anybody is unreasonable. Additional months in prison are not simply numbers. Those months have exceptionally severe consequences for the incarcerated individual. They also have consequences both for society which bears the direct and indirect costs of incarceration and for the administration of justice which must be at its best when, as here, the stakes are at their highest.

The appellate court concluded that “on remand, we are confident that Jenkins will eventually receive a sentence that properly punishes the crimes he committed. But Judge Suddaby, in imposing his sentence, went far overboard.”

United States v. Jenkins, Case No. 14-4295 (2nd Cir., Apr. 17, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

Unlike most changes in the Guidelines, the Sentencing Commission made the 2-level reduction retroactive to people already sentenced. Retroactivity under the Guidelines is not an automatic thing: a defendant must petition his or her sentencing court under 18 USC 3582(c)(2) for a sentence reduction pursuant to the retroactive Guideline. If eligible, an inmate still must convince the court that a reduction of his or her sentence ought to be awarded. Sentencing courts have wide discretion as to what to do with a sentence reduction motion, and district court decisions are nearly bulletproof.

Unlike most changes in the Guidelines, the Sentencing Commission made the 2-level reduction retroactive to people already sentenced. Retroactivity under the Guidelines is not an automatic thing: a defendant must petition his or her sentencing court under 18 USC 3582(c)(2) for a sentence reduction pursuant to the retroactive Guideline. If eligible, an inmate still must convince the court that a reduction of his or her sentence ought to be awarded. Sentencing courts have wide discretion as to what to do with a sentence reduction motion, and district court decisions are nearly bulletproof. Actually the odds for defendants were even better than that: 24% of the people who applied were not even eligible for the reduction, for reasons ranging from not having been sentenced under the drug guidelines to being locked in place by statutory mandatory minimum sentence. Only 8% of the 46,000 were denied on the merits (although due to sloppy district court records, the number could have been as high as 13%).

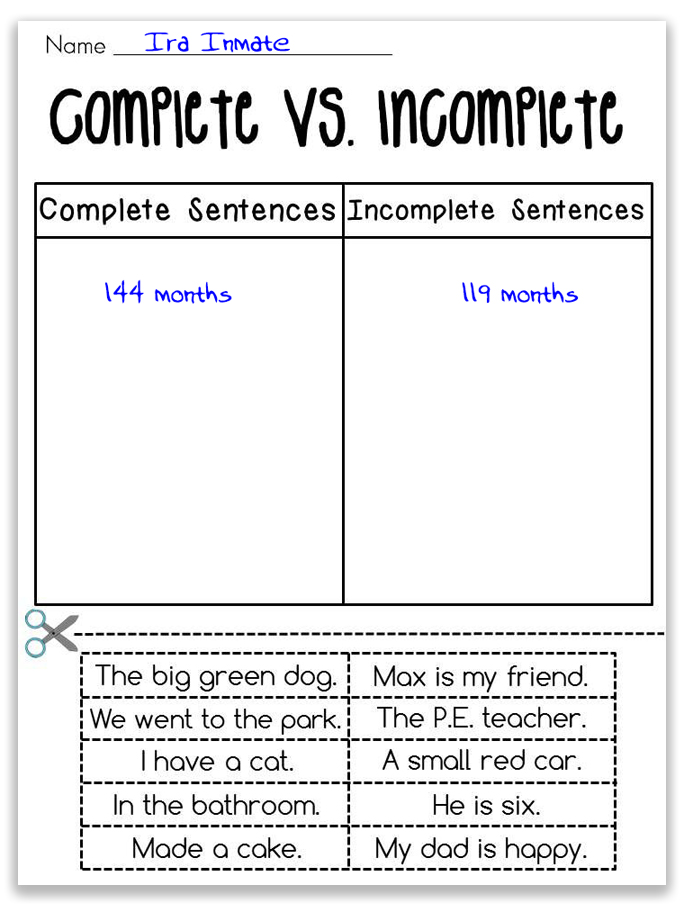

Actually the odds for defendants were even better than that: 24% of the people who applied were not even eligible for the reduction, for reasons ranging from not having been sentenced under the drug guidelines to being locked in place by statutory mandatory minimum sentence. Only 8% of the 46,000 were denied on the merits (although due to sloppy district court records, the number could have been as high as 13%). The average sentence was cut from 144 to 119 months, a 17% reduction. Of those receiving sentence reductions, 32% were convicted for methamphetamines, 28% for powder cocaine, 20% for crack, 9% for pot and 7% for heroin. The racial and ethnic distribution was 30% white, 33% black, and 41% Hispanic. Curiously enough, the defendant’s criminal history seemed to have no effect on likelihood of receiving a sentence cut, with novices and pros alike getting cuts at about the same rate.

The average sentence was cut from 144 to 119 months, a 17% reduction. Of those receiving sentence reductions, 32% were convicted for methamphetamines, 28% for powder cocaine, 20% for crack, 9% for pot and 7% for heroin. The racial and ethnic distribution was 30% white, 33% black, and 41% Hispanic. Curiously enough, the defendant’s criminal history seemed to have no effect on likelihood of receiving a sentence cut, with novices and pros alike getting cuts at about the same rate.