We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

IT’S A HOT MESS… BUT SENTENCING COMMISSION STILL PLANS TO VOTE ON FIRST OFFENDER PROPOSAL BY MAY 1

The U.S. Sentencing Commission met last Friday, and federal inmates were anxious. Chiefly, the anticipation was due to an email newsletters circulating in the institutions have been predicting adoption of a Guidelines change that will cut sentences.

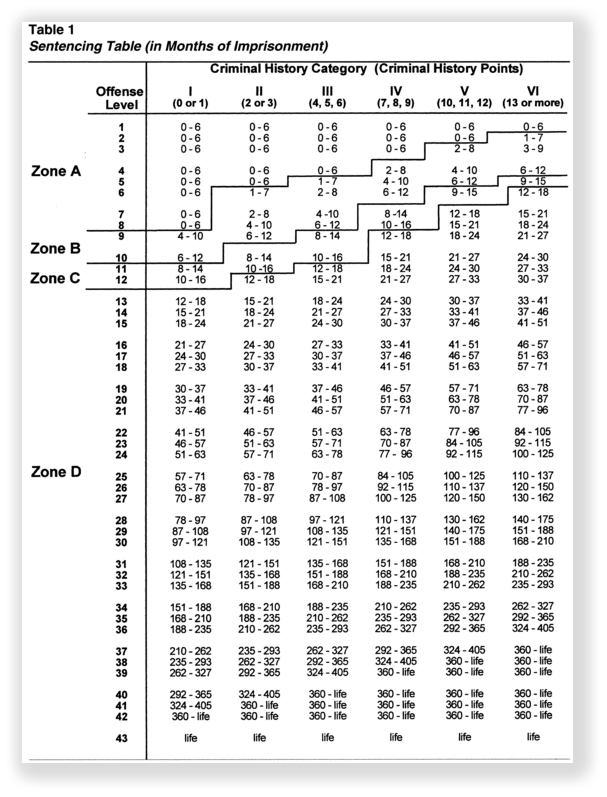

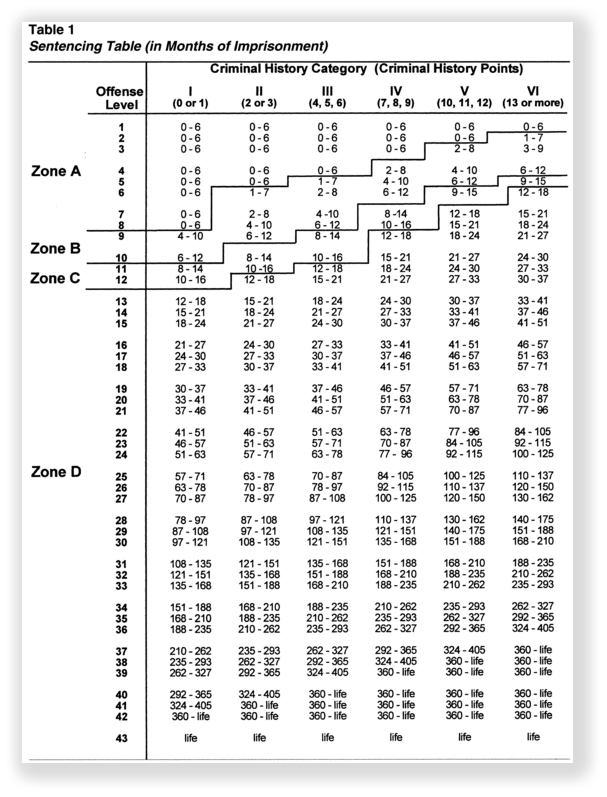

The change has been dubbed the “first offender proposal.” As the Guidelines are currently employed, the advisory sentencing ranges are set out in a chart. The y-axis of the chart is the Total Offense Level, determined by an assigned base offense level for the crime, along with additions and subtractions for various facts. The x-axis is the defendant’s criminal history.

The change has been dubbed the “first offender proposal.” As the Guidelines are currently employed, the advisory sentencing ranges are set out in a chart. The y-axis of the chart is the Total Offense Level, determined by an assigned base offense level for the crime, along with additions and subtractions for various facts. The x-axis is the defendant’s criminal history.

For example, a guy with a prior state conviction for felony burglary is convicted in federal court for supplying cocaine to two street-level dealers who sold for him. After being indicted, he pleads guilty. The amount of cocaine he moved may set the base level at 26. Because was a manager of two other people, 2 levels get added. But because he pled guilty as soon as he was indicted, 3 levels get subtracted for acceptance of responsibility. His Total Offense Level is 25. The prior felony gets him 3 criminal history points, placing him in Criminal History Category II.

For someone with a Total Offense Level of 25 and Crim History II, Guidelines sentencing table sets an advisory sentencing range of 63-78 months.

A few years ago, the Sentencing Commission noted that while some people had led exemplary lives up to their federal indictment, others fell in Criminal History I despite the fact they had some prior brushes with the law. A guy with a misdemeanor possession of drugs, for example, may have gotten 30 days suspended, and thus scored only one criminal history point, which kept him as Crim History I. Another guy may have done five years for a felony, getting out of prison in 2000. Because his prior bit ended more than 15 years ago, it no longer counted in the Guidelines criminal history score.

A few years ago, the Sentencing Commission noted that while some people had led exemplary lives up to their federal indictment, others fell in Criminal History I despite the fact they had some prior brushes with the law. A guy with a misdemeanor possession of drugs, for example, may have gotten 30 days suspended, and thus scored only one criminal history point, which kept him as Crim History I. Another guy may have done five years for a felony, getting out of prison in 2000. Because his prior bit ended more than 15 years ago, it no longer counted in the Guidelines criminal history score.

The Commission considered whether to modify the Criminal History guidelines to account for the difference between a virgin and someone who fell into Criminal History I more by luck than by conduct. It thus floated a proposal to reward the virginal defendant with a reduction in Total Offense Level. The proposal, made in December 2016, went nowhere, primarily because everything that was proposed then went nowhere: an unusually large number of USSC commissioner terms expired in December 2016, and due to Obama leaving and Trump arriving, no one got appointed to replace them right away. Without a quorum, nothing could happen.

By April 2017, the Commission was back to fighting strength, but too late to adopt proposed changes by May 1st. The USSC statute makes that date magic, because Sentencing Commission amendments must languish in front of Congress for six months (to give legislators a chance to veto any they don’t like) before becoming effective on November 1st. So the Commission decided to skip a 2017 Amendment cycle altogether.

In August, the Commission refloated the proposed amendments that were orphaned the previous January. The Commissioners are still trying to figure out whether the first offender proposal should reward any defendant with zero criminal history points, or whether it should only reward defendants who are truly tyros, having a lifetime history of no convictions. The USSC is also undecided whether to reward first offenders with a one- or a two-level reduction.

In August, the Commission refloated the proposed amendments that were orphaned the previous January. The Commissioners are still trying to figure out whether the first offender proposal should reward any defendant with zero criminal history points, or whether it should only reward defendants who are truly tyros, having a lifetime history of no convictions. The USSC is also undecided whether to reward first offenders with a one- or a two-level reduction.

There is one additional wrinkle: A change in the Guidelines, as a rule, only affects people who have not yet been sentenced. If it is to affect any of the 183,000-odd federal prisoners who are already doing time, the USSC must first declare it retroactive. Retroactivity is never a done deal. Instead, it depends on a lot of factors, some objective (such as whether retroactive motions for sentence reduction would clog the courts) and some subjective (such as whether fundamental fairness requires retroactivity).

That has not prevented a couple of outside businesses that take inmate money in exchange for “paralegal” services to trumpet that inmates need to hire them right now to assist in First Offender motions for reduction. This is despite the fact that (1) no one knows for sure whether the first offender proposal will in the USSC’s final 2018 amendment package sent to Congress; (2) no one knows for sure to whom and to what extent any first offender proposal would apply; and (3) no one knows whether the first offender proposal will ever be made retroactive. It is not all that comforting that the last change to the criminal history Guidelines, to eliminate a point previously added if the new offense was recent to a prior probation or prison term, was not made retroactive. But none of this deters hopemongers on the outside from collecting money from inmates and their families.

When the Sentencing Commission announced several weeks ago that last Friday’s meeting would include a “possible vote to publish proposed guideline amendments and issues for comment,” many thought that the vote would be to decide on which of the options in the first offender proposal to advance. Instead, the Commission advanced a synthetic-drug guideline, made changes in an immigration offense guideline, and voted on unspecified “technical amendments.” There was not a word on anything else.

Shortly after the meeting, however, the Commission clarified its rather opaque procedures. In a press release, the USSC noted toward the bottom of the page that “[t]oday’s proposals join other proposed amendments published in August 2017 that were held over from the previous amendment cycle. (Read “holdover” proposals”.) The Commission is expected to vote on the full slate of proposed amendments during the current amendment year ending May 1, 2018.”

Shortly after the meeting, however, the Commission clarified its rather opaque procedures. In a press release, the USSC noted toward the bottom of the page that “[t]oday’s proposals join other proposed amendments published in August 2017 that were held over from the previous amendment cycle. (Read “holdover” proposals”.) The Commission is expected to vote on the full slate of proposed amendments during the current amendment year ending May 1, 2018.”

So the Commission meant only to add to the holdover amendments it published last August, when the latest iteration of the “first offender proposal” was promulgated. Still, they could have said that at some point in their 17-minute meeting. But apparently, the first offender proposal may still be on track, and may still be in the package to be voted on by May 1.

We’re not just one-issue voters, complaining about the Commission’s failure to explain that the first offender proposal was still in the package lurching toward May 1. Ohio State University law professor and sentence guru Doug Berman noted last Friday in his sentencing blog that “my own cursory understanding of all these proposals suggests to me that the holdover proposal addressing first offenders and alternatives to incarceration may be the only very consequential proposed amendment potentially in the works….”

U.S. Sentencing Commission, USSC Proposes Amendments (Jan. 19, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root

The Romans had a phrase for it: “Cui bono?” Last week, the U.S. Sentencing Commission tried to answer that question about the First Step Act.

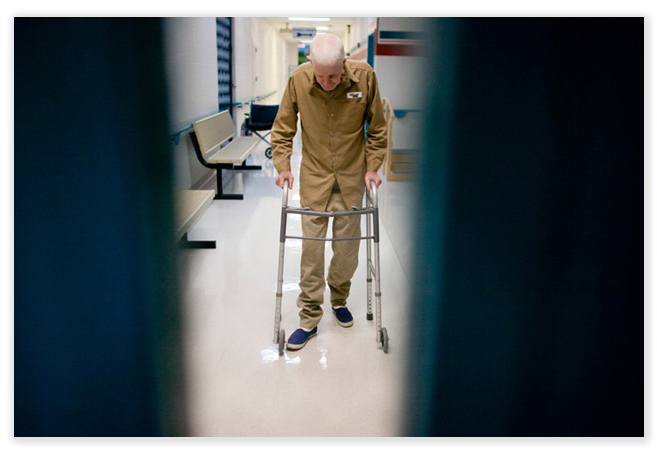

The Romans had a phrase for it: “Cui bono?” Last week, the U.S. Sentencing Commission tried to answer that question about the First Step Act. The elderly offender home detention program expanded by the Act has 1,880 inmates who are currently eligible (the right age, right offenses and right amount of time served). Of course, the EOHD program, unlike the other First Step programs, will see an influx of additional inmates who reach the right age and service of sentence.

The elderly offender home detention program expanded by the Act has 1,880 inmates who are currently eligible (the right age, right offenses and right amount of time served). Of course, the EOHD program, unlike the other First Step programs, will see an influx of additional inmates who reach the right age and service of sentence.