We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SENTENCING COMMISSION ROLLS OUT MINIMALIST 2025 AMENDMENT PROPOSAL

The United States Sentencing Commission yesterday adopted a slate of proposed amendments to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for the amendment cycle that will end on or before May 1, 2025, with the adoption of amendments to become effective next November.

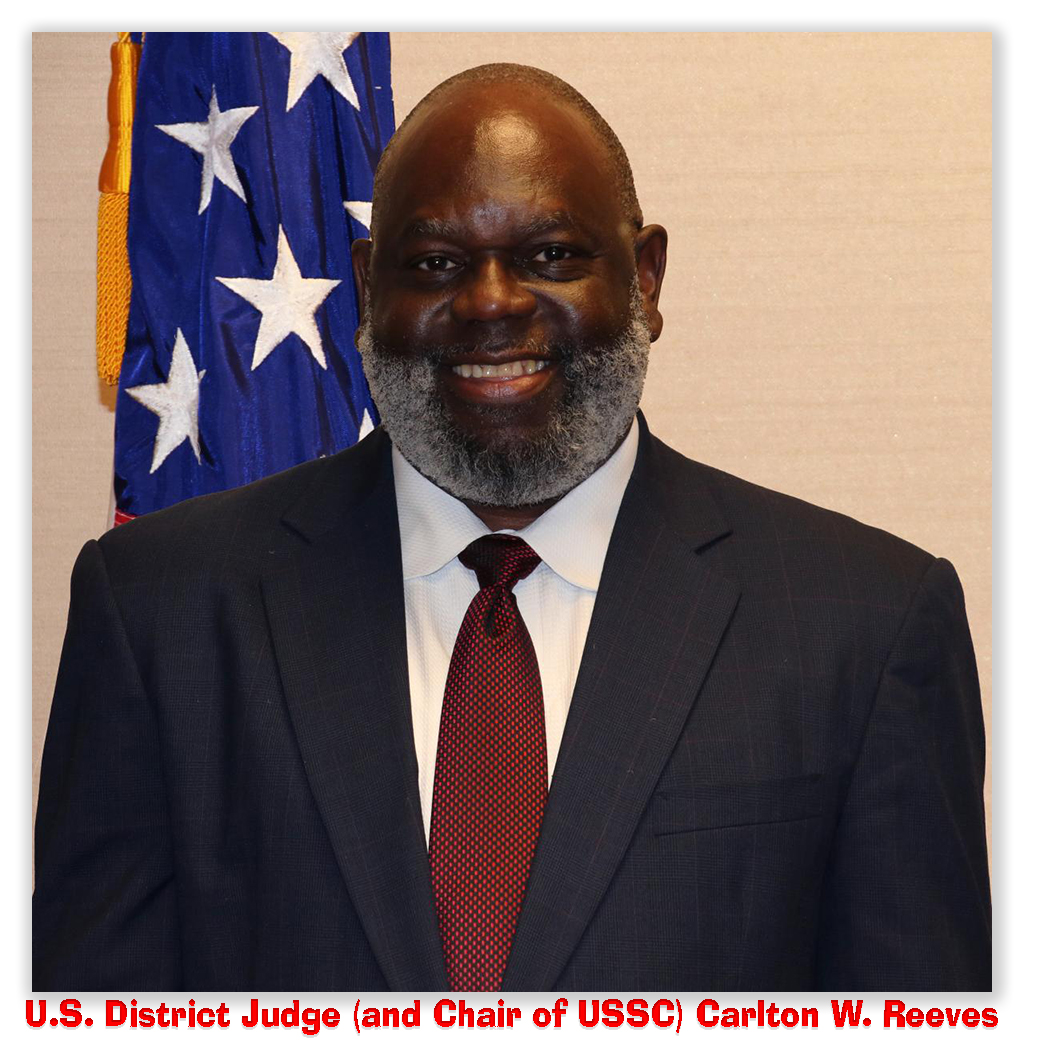

Anyone who thought the Commission might roll out a proposal to no longer enhance methamphetamine sentences because of purity – something that US District Judge Carlton Reeves (who is currently chairman of the USSC) ruled from the bench two years ago makes no sense – was disappointed (but see below).

Likewise, any federal prisoners hoping for a resolution to last August’s surprise decision to table retroactivity for four amendments that became effective last fall just found coal in their stockings. The Commission had proposed retroactivity for changes in Guidelines covering acquitted conduct, gun enhancements, Guidelines calculation where a defendant is convicted of an 18 USC § 922(g) felon-in-possession count, a 21 USC § 841 drug trafficking count and a separate 18 USC § 924 gun conviction; and a change in the drug Guidelines to tie mandatory and high base offense levels to statutory maximum sentences instead of more complex factors that inflate sentencing ranges.

Likewise, any federal prisoners hoping for a resolution to last August’s surprise decision to table retroactivity for four amendments that became effective last fall just found coal in their stockings. The Commission had proposed retroactivity for changes in Guidelines covering acquitted conduct, gun enhancements, Guidelines calculation where a defendant is convicted of an 18 USC § 922(g) felon-in-possession count, a 21 USC § 841 drug trafficking count and a separate 18 USC § 924 gun conviction; and a change in the drug Guidelines to tie mandatory and high base offense levels to statutory maximum sentences instead of more complex factors that inflate sentencing ranges.

Generally, changes in the Guidelines do not apply to people who have already been sentenced, but Guideline 1B1.10 addresses the rare occasions where a Guideline change is retroactive, providing prisoners already sentenced with a chance for a time reduction.

I wrote at the time that the Commission was perhaps responding to criticism heaped on it for adopting amended Guideline 1B1.13(b)(6), which permits judges to grant compassionate release where a prisoner’s sentence could not be imposed today because of changes in the law that occurred after the sentence was imposed. After the Commission adopted the amended 1B1.13 in April 2023, Sens John Kennedy (R-LA), Ted Cruz (R-TX), John Cornyn (R-TX), Tom Cotton (R-AR) and Marco Rubio (R-FL) introduced the Consensus in Sentencing Act (S.4135) to require the Commission to achieve “bipartisan agreement to make major policy changes” by ”requiring that amendments to the Guidelines receive five votes from the Commission’s seven voting members.”

At the time, Kennedy complained that “[i]n recent years, the Commission has lost its way and begun forcing through amendments on party-line votes.” The Commission has seven voting members. No more than four members can belong to the same political party.

At the time, Kennedy complained that “[i]n recent years, the Commission has lost its way and begun forcing through amendments on party-line votes.” The Commission has seven voting members. No more than four members can belong to the same political party.

S.4135 never went anywhere, and it will die with the end of the 118th Congress in 10 days or so. Nevertheless, last June, retired US District Judge John Gleeson, a member of the Commission, met with Kennedy and – according to the Senator – “acknowledged the concerns raised about the Commission’s recent practices and confirmed that the Commission will return to making changes on a bipartisan basis.”

“I look forward to seeing the fruits of this commitment,” Kennedy said at the time.

The Commission is now seeking to harvest those fruits by issuing a request that the public comment on whether “it should provide further guidance on how the existing criteria for determining whether an amendment should apply retroactively are applied” and “[i]f so, what should that guidance be? Should it revise or expand the criteria? Are there additional criteria that the Commission should consider beyond those listed in the existing Background Commentary to § 1B1.10?”

The answer to whether there should be additional criteria is self-evident, especially because the same players (except for Rubio, leaving Congress for a position in President-elect Trump’s Cabinet) will be back in the Senate.

What the Commission decides will only partially address the Senators’ principal beef against any USSC proposal that passes on a 4-3 vote (at least until the Republicans again hold a majority on the Commission).

What the Commission decides will only partially address the Senators’ principal beef against any USSC proposal that passes on a 4-3 vote (at least until the Republicans again hold a majority on the Commission).

Third Circuit Judge L. Felipe Restrepo’s USSC term expires next October, the earliest chance Trump will have to tip the balance of the Commission to conservative. Given that Trump’s previous nominees to the Commission (never approved by the Senate) included US District Judges Danny Reeves and Henry “Hang ‘em High” Hudson, the likelihood that 4-3 Commission decisions will start looking good to Kennedy, Cruz and the others is fairly high.

Other USSC proposals for the amendment cycle include

• creating an alternative to the “categorical approach” used in the career offender guideline to determine whether a conviction qualifies a defendant for enhanced penalties;

• addressing the guidelines’ treatment of devices designed to convert firearms into fully automatic weapons (Glock switches and drop-in auto sears);

• adding a provision to the use of a stolen gun enhancement that requires that the defendant knew the gun was stolen; and

• resolving a circuit split on whether a traffic ticket in an “intervening arrest” that can serve to bump up criminal history.

Public comments are due by February 3, 2025, with replies due by February 18, 2025.

Curiously, Judge Reeves said, “Over the next month, the Commission will consider whether to publish additional proposals that reflect the public comment, stakeholder input, and feedback from judges that we have received over the last year – including at the roundtables we have held in recent months on drug sentencing and supervised release.”

Curiously, Judge Reeves said, “Over the next month, the Commission will consider whether to publish additional proposals that reflect the public comment, stakeholder input, and feedback from judges that we have received over the last year – including at the roundtables we have held in recent months on drug sentencing and supervised release.”

Whether this is a teaser that changes in the Commission’s approach to meth will be on the table is unclear.

Sentencing Commission meeting video (December 19, 2024)

Sentencing Commission Public Hearing (Video) (August 8, 2024)

Sentencing Commission, Final Priorities for Amendment Cycle (August 8, 2024)

S.4135, Consensus in Sentencing Act

Sen John Kennedy, Kennedy confirms that Sentencing Commission will return to bipartisan agreement for changes to Sentencing Guidelines (June 3, 2024)

USSC, Issue For Comment: Criteria for Selecting Guideline Amendments Covered by §1B1.10 (December 19, 2024)

USSC News Release, U.S. Sentencing Commission Seeks Comment on Proposals to Promote Public Safety And Simplify Federal Sentencing (December 19, 2024)

USSC, Summary of Proposed 2025 Amendments (December 19, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root