We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

I SAY ‘TO-MA-TO,’ YOU SAY ‘TO-MAH-TO’… IT DOESN’T MATTER

The dark side of United States v. Booker – the 20-year-old Supreme Court case that held the Sentencing Guidelines must be advisory and not mandatory – is the untethering of federal district court judges to sentence as they see fit.

At first blush, that sounds like a feature and not a bug. However, a pair of cases handed down this week shows that it can lead to disparate and sometimes unreasonable results.

Alexander Olson, a man easily led by others, was one of eight political wackadoodles who thought that setting fire to four Walmart stores would force the company to pay employees more, feed the homeless, limit executive pay and adopt an additional slate of progressive wish-list policies.

(In fairness, my wife was tempted to torch our local Walmart yesterday over $6.00-a-dozen eggs, but no jury of Walmart shoppers would ever convict her for that).

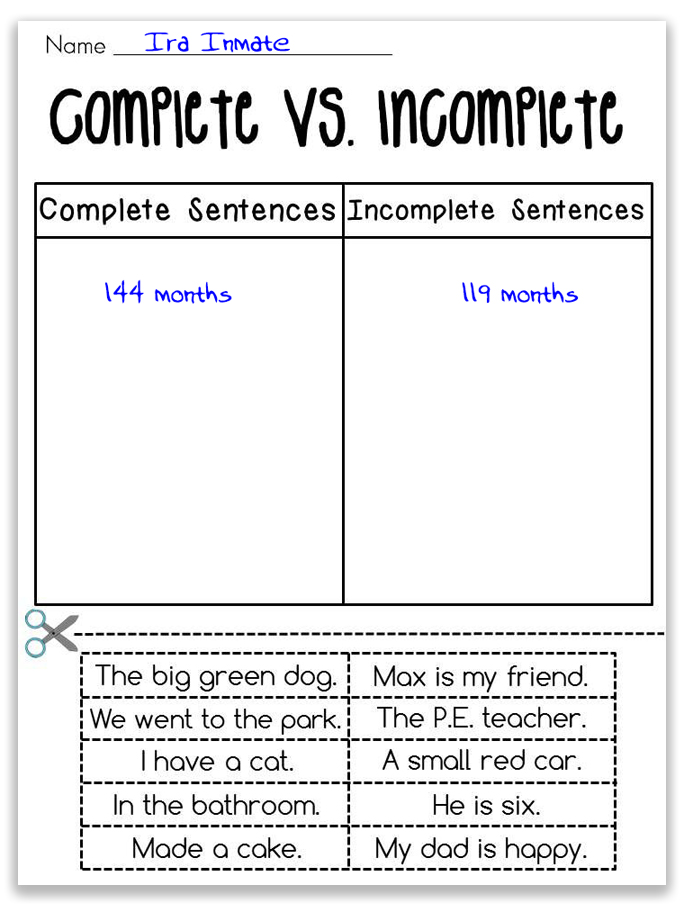

Alex and his fellow travelers were charged with conspiracy to commit arson in violation of 18 USC § 844(n). He pled guilty, with sentencing guidelines working out to 41-51 months, and a statutory sentencing mandatory minimum of 60 months (which by law, became the minimum and maximum of Alex’s Guidelines range). But at sentencing, the judge decided an upward variance to 180 months (15 years) was appropriate, despite the fact Alex was not the ringleader and evidence showed he suffered from prior psychological abuse that made him easily led by males from whom he craved validation.

The 180-month sentence was 60 months shy of that statute’s maximum 240 months, and the judge paid lip service to the 18 USC § 3553(a) sentencing factors even while discounting the mitigating evidence that didn’t fit with the court’s worldview.

The court called the sentence of three times Alex’s Guideline range an upward variance, but later in its written explanation of reasons, referred to it as a departure.

The court called the sentence of three times Alex’s Guideline range an upward variance, but later in its written explanation of reasons, referred to it as a departure.

A variance and a departure both result in a sentence outside the advisory guidelines range but reach that result in different ways. A variance occurs when a court determines that a guidelines sentence will not adequately further the purposes reflected in 18 USC § 3553(a). A departure refers to non-Guidelines sentences imposed under the framework set out in the Guidelines departure provisions set out in USSG Chapter 5K. Advance notice to the parties is generally required for a departure but not for a variance.

Significantly, the court said, “I find the advisory guidelines range is not appropriate to the facts and circumstances of this case, and the sentence here, whether an upward departure or a variance, I find appropriate.”

The 11th Circuit this week said it may have been a variance, may have been a departure, but the distinction did not matter because the district court would have imposed the same sentence regardless of which it was and the sentence – which was well below the statutory maximum – was substantively reasonable. “Under those circumstances, any error in the court’s application of a guidelines issue,” the 11th said, “including a departure issue, is harmless.”

In the 7th Circuit, a different take on the same issue: Chris Easterling tried to rob a Walgreens store by pulling a gun and telling the cashier, “Let’s get this going, babe.” She was uninterested in getting whatever he had in mind going, fleeing instead. Chris couldn’t open the register himself, so he left to enjoy a few more minutes of freedom before being charged with attempted 18 USC § 1951 Hobbs Act robbery and an 18 USC § 924(c) count for using the gun (among other offenses).

In the 7th Circuit, a different take on the same issue: Chris Easterling tried to rob a Walgreens store by pulling a gun and telling the cashier, “Let’s get this going, babe.” She was uninterested in getting whatever he had in mind going, fleeing instead. Chris couldn’t open the register himself, so he left to enjoy a few more minutes of freedom before being charged with attempted 18 USC § 1951 Hobbs Act robbery and an 18 USC § 924(c) count for using the gun (among other offenses).

Chris pled guilty, with a Guidelines advisory range of 57 to 71 months in prison for the Hobbs Act violation and a consecutive mandatory 84 months’ imprisonment, to run consecutively to the Hobbs Act sentence (for a total range of 141-155 months).

At sentencing, the court sentenced Chris to 239 months, 155 months for the Hobbs Act robbery and a consecutive 84 months for the § 924(c), a sentence 54% higher than the high end of his advisory sentencing range just one month shy of the 240-month statutory maximum sentence for Hobbs Act robbery. The court said Chris’s conduct and his “persistent and repeated history of violence” called for a “significant sentence” to protect the public.

The Supreme Court then decided in United States v. Taylor that attempted Hobbs Act robbery – which is what Chris was convicted of – could not support a § 924(c) count because it was not categorically a crime of violence. But when Chris went back for resentencing without the consecutive 84-month sentence (new sentencing range of 84-105 months), the district court again slapped the 239-month sentence on him, saying that “nothing had changed” in Chris’s history or the nature of the offense.

Chris appealed that sentence, too. While the appeal was pending, the Sentencing Commission changed its criminal history Guidelines in a way that would reduce Chris’s category by one level and drop his new sentencing range to 70-87 months. The government argued that the case should not be remanded for resentencing again, because the district court had checked a box on the Statement of Reasons form that every court must submit after a criminal sentence that says: “In the event the guideline determination(s) made in this case are found to be incorrect, the court would impose a sentence identical to that imposed in this case.”

Not good enough, the 7th said this week. “Putting aside the fact that the district court could not grapple with a Guidelines amendment that did not exist yet, this checked box is insufficient to prevent remand. We have previously held that a bare, boilerplate assertion – a conclusory comment tossed in for good measure – will not ordinarily suffice to hold a Guidelines error harmless.”

The Circuit ruled, “We require a district court to assure us that it would impose the same sentence again by specifically addressing the contested issue… Here, the court was unable to do so. We will not presume that a district court is so intransient that nothing the Commission does and no possible change to the Guidelines could sway its prior decision.”

The Circuit ruled, “We require a district court to assure us that it would impose the same sentence again by specifically addressing the contested issue… Here, the court was unable to do so. We will not presume that a district court is so intransient that nothing the Commission does and no possible change to the Guidelines could sway its prior decision.”

United States v. Olson, Case No. 23-11939, 2025 U.S. App. LEXIS 2351 (11th Cir. Feb. 3, 2025)

United States v. Easterling, Case No. 23-1143, 2025 U.S. App. LEXIS 2376 (7th Cir. Feb. 3, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root

The 7th Circuit last week held that the same rule benefitted Rashod Bethany. Rashod was sentenced for a crack conspiracy in 2013, but later won a

The 7th Circuit last week held that the same rule benefitted Rashod Bethany. Rashod was sentenced for a crack conspiracy in 2013, but later won a