We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

WHY SHOULD IT MATTER?

Consumers of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines – the courts that apply them, the lawyers that argue them, and the defendants that suffer under them – all have experience with the Byzantine nature of the code: enhancements are many and malleable, timelines are flexible as needed, and the quantum of evidence needed to jack up offense levels seems to fluctuate like political approval ratings.

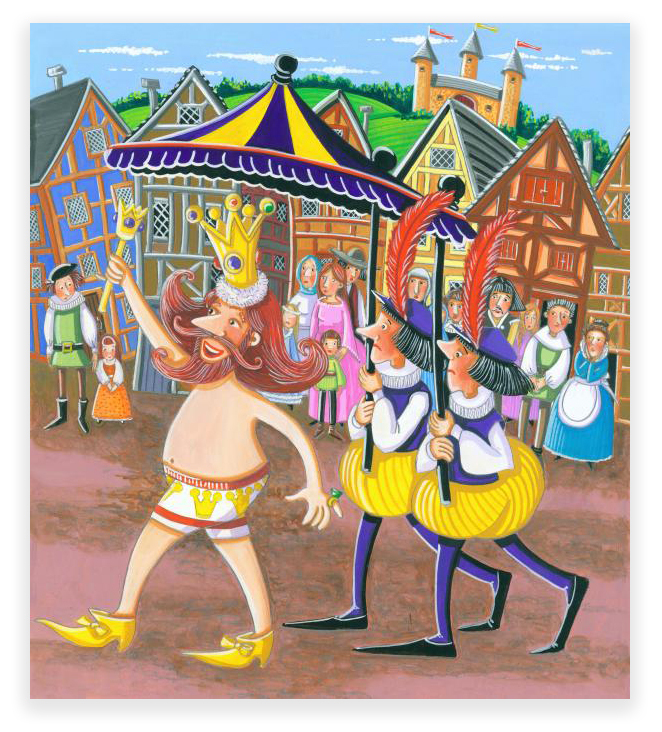

A refreshing 7th Circuit decision handed down Monday declared emphatically that the Guidelines emperor has no clothes. Crane Marks, who had pled guilty to conspiring to distributing heroin, was sentenced to 108 months, a sentence that was “either well above or well below the advisory range under the Sentencing Guidelines, depending on one issue,” the Court said. The district court decided the issue against Crane, but did so in a way that was both legally and factually defective.

A refreshing 7th Circuit decision handed down Monday declared emphatically that the Guidelines emperor has no clothes. Crane Marks, who had pled guilty to conspiring to distributing heroin, was sentenced to 108 months, a sentence that was “either well above or well below the advisory range under the Sentencing Guidelines, depending on one issue,” the Court said. The district court decided the issue against Crane, but did so in a way that was both legally and factually defective.

Most of us who have spent any time at all in courtrooms have heard judges disgustedly ask parties – either the plaintiff or defendant, and sometimes both – “why are you here?” It hardly ever is asked as eloquently as it was in this case. The Circuit complained,

In all candor, [the] one issue [in this case] seems astonishingly technical and trivial. It has nothing to do with Marks’ culpability or the larger goals of sentencing. As we explain below, the issue is whether, when Marks was imprisoned on his fourth state drug conviction in 2000, he also had his state parole revoked on any of his earlier state drug convictions and was re‐imprisoned on that revocation as well. From this description of the issue, we hope readers will agree that this is one of those guideline issues that should prompt the sentencing judge to ask why the judge or anyone else should care about the an‐swer.

Because the issue seems so technical and trivial, we have examined the record in this case for any signs that the judge would have given Marks the same sentence regardless of how the technical criminal history issue was resolved. We found no such signs, however, so we have considered the technical guideline issue on the merits.

The issue was straightforward enough. Crane had enough prior state drug convictions to be a career offender under USSG Sec. 4B1.1, which would subject him to a dramatically higher sentencing range. However, for a prior drug sentence to count, it had to be otherwise eligible for criminal history points, meaning that Crane would have had to have been in prison for it within 15 years of the current offense.

The government and Crane agreed he was not a career offender, because he got out of prison on one of his qualifying priors, from 1994, more than 15 years before his current crime. This would have set his sentencing range at 51-63 months. But the Probation Officer writing the presentence report found some handwritten state prison records saying Crane had had his parole revoked on the 1994 case in 2000, which would put imprisonment on the offense within the 15-year window and make the 1994 case countable. The records showed that his parole was revoked, and he was “in the custody” of the state department of corrections. The Probation Officer – and the court – concluded Crane was a career offender. His career offender guidelines were 151-188 months, but the court sentenced him well below that at 108 months.

The government and Crane agreed he was not a career offender, because he got out of prison on one of his qualifying priors, from 1994, more than 15 years before his current crime. This would have set his sentencing range at 51-63 months. But the Probation Officer writing the presentence report found some handwritten state prison records saying Crane had had his parole revoked on the 1994 case in 2000, which would put imprisonment on the offense within the 15-year window and make the 1994 case countable. The records showed that his parole was revoked, and he was “in the custody” of the state department of corrections. The Probation Officer – and the court – concluded Crane was a career offender. His career offender guidelines were 151-188 months, but the court sentenced him well below that at 108 months.

Probation officers work for the U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services, a judicial agency. They are often considered by the district court judges to be their trusted employees. This unhealthy familiarity, in our opinion, leaves judges way too willing to accept anything the probation officer says, even when both the government and the defendant disagree. So it was in this case.

The Court of Appeals was not wearing the same blinders. It concluded “that the court made both a legal error and a factual error. The legal error was that the court did not make the finding needed to treat Marks as a career offender under the Guidelines. The factual problem is that the court was not presented with reliable evidence from which it could have found that Marks was imprisoned on a revocation of parole on any earlier conviction. That means that Marks does not qualify, technically, as a career offender. His advisory guideline sentencing range is lower than the range found by the district court.”

The legal problem was that the state department of corrections treated anyone on home confinement, electronic monitoring or in prison as being “in custody.” This meant that the notation that Crane was “in custody” was irrelevant: only if he was actually locked up within the 15 years would the prior offense count. As the Circuit put it, “The broad concept of “custody” is not enough under Sec. 4A1.2(k)(2). The focus is “incarceration.” Proving that Marks’ parole terms did not expire until 2000 was not enough—the government had to show that Marks was incarcerated on at least one of those convictions.”

The legal problem was that the state department of corrections treated anyone on home confinement, electronic monitoring or in prison as being “in custody.” This meant that the notation that Crane was “in custody” was irrelevant: only if he was actually locked up within the 15 years would the prior offense count. As the Circuit put it, “The broad concept of “custody” is not enough under Sec. 4A1.2(k)(2). The focus is “incarceration.” Proving that Marks’ parole terms did not expire until 2000 was not enough—the government had to show that Marks was incarcerated on at least one of those convictions.”

The factual problem was that the district court lacked reliable evidence to support application of the career‐offender Guideline. As a general rule, a sentencing judge may rely on a presentence report if it “is well‐supported and appears reliable,” the Circuit said. “But if a presentence report contains nothing but a naked or unsupported charge,” the defendant’s denial will suffice to call the report’s accuracy into doubt. Similarly, if the presentence report “omits crucial information, leaving ambiguity on the face of that document,” the government has the burden of independently demonstrating the accuracy of the report.”

Here, the records contained no narrative showing that Crane was given a new term of imprisonment for violating parole, or whether he was merely noted as being in custody on a potential parole violation. The fact that his sentence on 1994 conviction “was discharged only a few months after he pled guilty to the 2000 charge,” the Circuit said, “suggests that no revocation occurred. And it is difficult to understand why, if Marks’ parole was actually revoked, the government could not have supported the presentence report with a copy of the order of revocation.”

It seems so much like counting angels on the heads of pins. Had the trial judge stated on the record that his sentence would be 108 months with or without the career offender finding, the 7th would have simply called it a day. But without being able to tell from the record how the faulty career offender status influenced the trial court, the Circuit had no option but to remand the case for resentencing.

It seems so much like counting angels on the heads of pins. Had the trial judge stated on the record that his sentence would be 108 months with or without the career offender finding, the 7th would have simply called it a day. But without being able to tell from the record how the faulty career offender status influenced the trial court, the Circuit had no option but to remand the case for resentencing.

United States v. Marks, Case No. 15-2862 (7th Cir., July 24, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

Some documents are confidential? Ukraine is run by Nazis? Inflation is transitory? Ipse dixits, every one of them…

Some documents are confidential? Ukraine is run by Nazis? Inflation is transitory? Ipse dixits, every one of them…