We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

LORD, NELSON

Lawyers are always plumbing the depths of cases for new angles they can use in defending their clients, and that’s how it should be. After all, we had the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause for nearly a century before legal thinking accepted that it meant we could not deny lodging, meals and voting to those of a different race. And the 1st Amendment was on the books for 175 years before courts accepted that we had a right to be wrong in our speech about public events and public people without risking financial ruination.

Lawyers are always plumbing the depths of cases for new angles they can use in defending their clients, and that’s how it should be. After all, we had the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause for nearly a century before legal thinking accepted that it meant we could not deny lodging, meals and voting to those of a different race. And the 1st Amendment was on the books for 175 years before courts accepted that we had a right to be wrong in our speech about public events and public people without risking financial ruination.

But sometimes, as Sigmund Freud famously probably never said, “a cigar is just a cigar.”

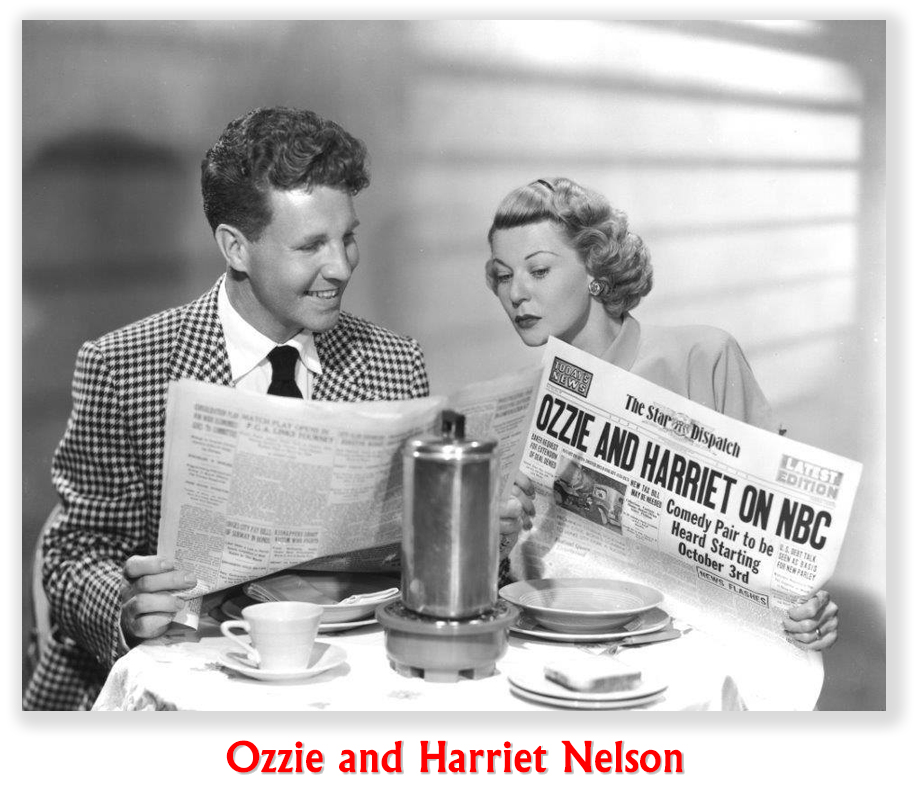

A year ago, the Supreme Court grappled with a case named Nelson v. Colorado, a matter that seemed to us to so straightforward as to make us wonder why it was even being debated. Two folks from Colorado, in separate cases, had been convicted of crimes and – as part of the punishment – were made to pay court costs, fees and restitution. Both of them had their convictions overturned, but Colorado law required that before they could get back the money paid for the costs, fees and restitution, they had to jump through an additional hoop: they had to prove they were innocent.

A year ago, the Supreme Court grappled with a case named Nelson v. Colorado, a matter that seemed to us to so straightforward as to make us wonder why it was even being debated. Two folks from Colorado, in separate cases, had been convicted of crimes and – as part of the punishment – were made to pay court costs, fees and restitution. Both of them had their convictions overturned, but Colorado law required that before they could get back the money paid for the costs, fees and restitution, they had to jump through an additional hoop: they had to prove they were innocent.

Proving one’s innocence is a lot different from the government not being able to prove one guilty. And it is a step that the Supreme Court rejected in Nelson. The Court said that the 14th Amendment’s right to due process meant that the State could not retain funds taken from the defendants simply because their convictions were in place when the funds were taken. Once the convictions were erased, the Court said, the presumption of innocence was restored. “Colorado may not presume a person, adjudged guilty of no crime, nonetheless guilty enough for monetary exactions,” the Court said. Simply enough, the Supremes said, when the conviction was overturned, the defendants were defendants no longer, and were presumed to be as innocent as any other Colorado citizen. Thus, the costs, fines and restitution had to be returned to them, no questions asked.

When we read Nelson at the time, we thought that the result was pretty obvious, but – while an interesting addition to due process jurisprudence – a matter of little significance to other areas of criminal law. But we did not reckon with the creativity of attorneys.

In the Bloomberg BNA Criminal Law Reporter last week, well-known and respected federal criminal defense attorney Alan Ellis and his associates penned an article entitled Does an Acquittal Now Matter at Sentencing? Reining in Relevant Conduct Through a Recent Restitution Ruling. In the piece, Mr. Ellis described how federal courts routinely rely on acquitted or dismissed conduct – allegations of wrongdoing that a jury either rejected or never even considered – in setting federal criminal sentences. Mr. Ellis argued that in the wake of Nelson, the presumption of innocence attached to defendant with respect to any acquitted or uncharged conduct. Thus, federal judges could not constitutionally punish such acquitted or uncharged conduct in setting sentences. Or, as Mr. Ellis put it:

In the Bloomberg BNA Criminal Law Reporter last week, well-known and respected federal criminal defense attorney Alan Ellis and his associates penned an article entitled Does an Acquittal Now Matter at Sentencing? Reining in Relevant Conduct Through a Recent Restitution Ruling. In the piece, Mr. Ellis described how federal courts routinely rely on acquitted or dismissed conduct – allegations of wrongdoing that a jury either rejected or never even considered – in setting federal criminal sentences. Mr. Ellis argued that in the wake of Nelson, the presumption of innocence attached to defendant with respect to any acquitted or uncharged conduct. Thus, federal judges could not constitutionally punish such acquitted or uncharged conduct in setting sentences. Or, as Mr. Ellis put it:

Acquitted conduct cannot be used to penalize (or increase a penalty) because an acquittal, by any means, restores the presumption of innocence. And no one may be penalized for being presumed innocent.

Our email inbox exploded with questions from federal inmates wondering whether Attorney Ellis might be onto something. Our response is a thundering, “Uh… not really.”

Mr. Ellis is right that 18 USC 3661 holds that there is no limit “on the information concerning the background, character, and conduct of a person convicted of an offense which a court of the United States may receive and consider for the purpose of imposing an appropriate sentence.” He is also right that the provisions of 18 USC 3661 are limited by the Constitution. For example, a court may not consider a defendant’s race, national origin or faith in imposing a sentence, regardless of the seeming lack of boundaries in Sec. 3661. But his conclusion that a court cannot consider acquitted or dismissed conduct is an oversimplification.

First, the punishment being meted out is not being imposed because of a crime of which the defendant was not convicted. There’s a real difference between punishing some who has not been found to have committed any crime and setting the punishment of someone who has been found to have committed a crime. In Nelson, the defendants were being punished financially where they had been convicted of nothing. In the case of a federal prisoner, the sentence is precisely  because the defendant was convicted of a crime, either by his own admission in a guilty plea or because a jury found him guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

because the defendant was convicted of a crime, either by his own admission in a guilty plea or because a jury found him guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

For each federal crime, Congress has prescribed a penalty (for example, from 0-10 years for possession of a gun by a convicted felon, or 5-40 years for possession with intent to sell 500 grams or more of cocaine). If a defendant is convicted of one of those offenses, any sentence within the statutory range is constitutionally permissible. By contrast, the Colorado scheme invalidated in Nelson let the state continue the imposition of a penalty absent a conviction. That offended due process.

Second, Mr. Ellis noted a prior Supreme Court decision, United States v. Watts, holding that facts relied on by a judge in setting a sentence must be found by a preponderance of the evidence. However, he blithely suggested that Nelson implicitly overruled Watts, rather than considering that maybe the holdings do not clash at all. Watts required first that a defendant be guilty of a criminal offense, and it nowhere countenanced sentencing a defendant in excess of the statutory maximum. Instead, it simply held that under 18 USC 3661 and the due process clause, a judge may consider information from acquitted counts, provided the information proved the defendant’s involvement by a preponderance. This holding does not clash with Nelson, because the defendant is never punished in excess of what the statute allows for the crime that was committed.

Third, Mr. Ellis is flat wrong when he says that “the reasoning of Nelson thus compels the conclusion that Watts has been effectively overruled.” The Supreme Court has repeatedly and clearly held that “Our decisions remain binding precedent until we see fit to reconsider them, regardless of whether subsequent cases have raised doubts about their continuing vitality.” While his prognostication that the Supreme Court would overrule Watts if the issue ever gets before it again is one we can neither prove nor disprove, we would suggest that what little tension the Watts caused among the justices is probably dissipated since Booker made the Guidelines advisory rather than mandatory.

Finally, a primary issue in Nelson was what standard to apply, the due process inspection of Mathews v. Eldridge, or the more state-friendly standard from Medina v. California, which just asked whether the procedure required by the state for the defendants to get their money back offended “a fundamental principle of justice.” The Supreme Court applied the more defendant-friendly Mathews standard, because the issue in the case was “the continuing deprivation of property after a conviction has been reversed or vacated, with no prospect of reprosecution.” The Court thus defined the case as one arising where “no further criminal process is implicated.”

Finally, a primary issue in Nelson was what standard to apply, the due process inspection of Mathews v. Eldridge, or the more state-friendly standard from Medina v. California, which just asked whether the procedure required by the state for the defendants to get their money back offended “a fundamental principle of justice.” The Supreme Court applied the more defendant-friendly Mathews standard, because the issue in the case was “the continuing deprivation of property after a conviction has been reversed or vacated, with no prospect of reprosecution.” The Court thus defined the case as one arising where “no further criminal process is implicated.”

Use of acquitted conduct or dismissed conduct information in a federal sentencing, however, occurs in the middle of criminal process, at a time when further such process is almost a foregone conclusion. That makes use of acquitted or dismissed conduct information at sentencing a much different matter than the situation at issue in Nelson.

Don’t get us wrong: we would applaud a world in which judges were limited to only using information at sentencing that had been vetted by the “reasonable doubt” standard. But that is not the law, and despite Mr. Ellis’ creative interpretation, Nelson does nothing to change that.

Ellis, Alan, et al, Does an Acquittal Now Matter at Sentencing? Reining in Relevant Conduct Through a Recent Restitution Ruling, 102 CrL 364 (Jan. 17, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root