We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

HILL V. LOCKHART ‘OBJECTIVE” TEST DEFANGED

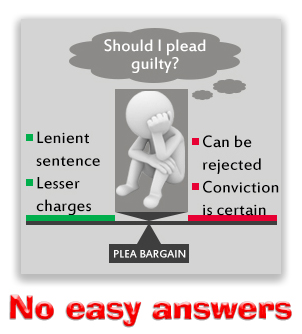

If a post-conviction petitioner argues in a 28 USC 2255 motion that he or she would never have taken a plea deal if defense counsel had done a competent job of explaining it, the courts have held that the prisoner must show (1) the advice was deficient (either bad or missing altogether); and (2) but for the bad representation, he or she would have rejected the plea and gone to trial. This is the Hill v. Lockhart test, from a 1985 Supreme Court decision.

A prisoner might have a lot of reasons for going to trial that have nothing to do with whether he or she can win. But over the years, the government has convinced courts that if the petitioner had no reasonable chance of winning at trial, he or she cannot prove that but for the lousy advice, he or she would have rolled the dice with a jury.

A prisoner might have a lot of reasons for going to trial that have nothing to do with whether he or she can win. But over the years, the government has convinced courts that if the petitioner had no reasonable chance of winning at trial, he or she cannot prove that but for the lousy advice, he or she would have rolled the dice with a jury.

Korean-American restaurant owner Jae Lee was in that boat. Jae had moved to the United States from South Korea with his parents when he was 13. In the 35 years he spent in this country, Jae has never returned to South Korea, but neither had he become a U. S. citizen, living instead as a lawful permanent resident.

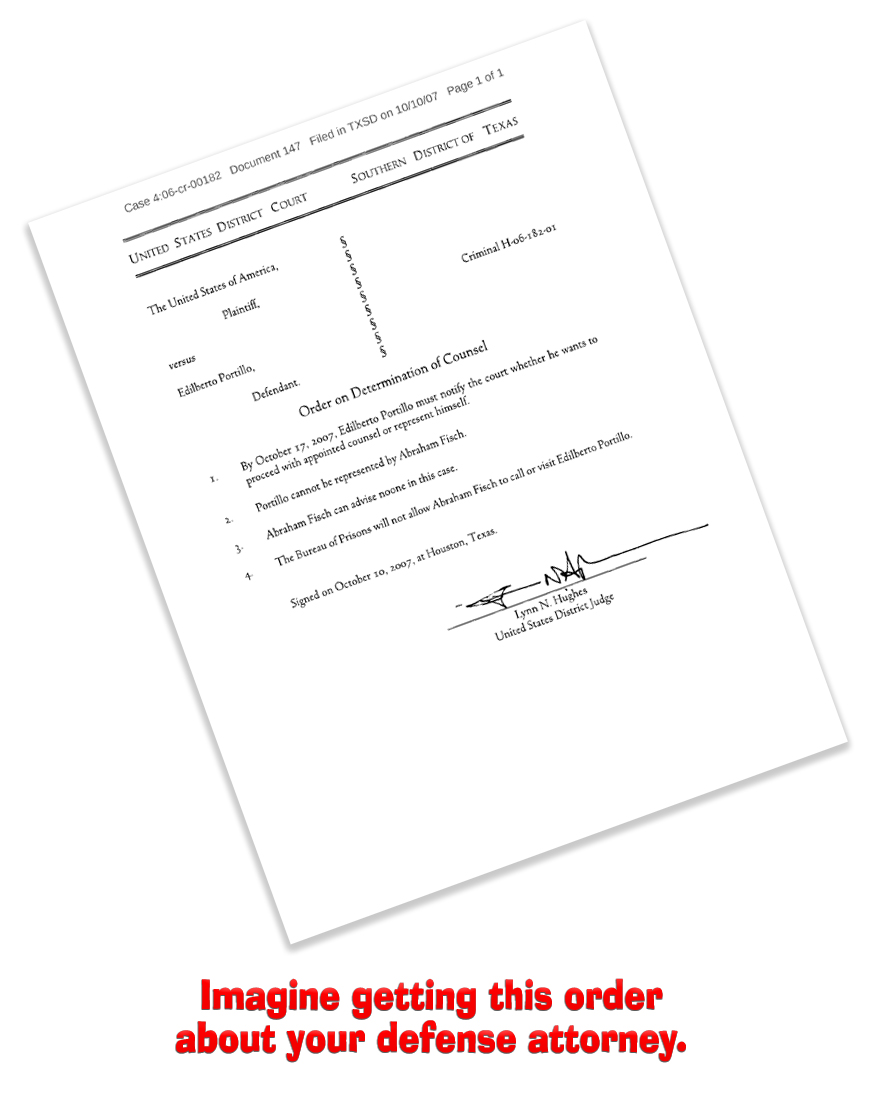

In 2008, federal law enforcement found drugs, cash, and a loaded rifle in Jae Lee’s house. Jae admitted that the drugs were his, and a grand jury indicted him. His attorney talked pleas with the Government. During the plea process, Jae repeatedly asked his attorney whether he would face deportation; his attorney assured him that he would not be deported as a result of pleading guilty. Based on that assurance, Lee accepted a plea and was sentenced to a year and a day in prison.

The attorney was dead wrong. Jae was subject to mandatory deportation as a result of the plea. When Jae learned of this consequence, he filed a 2255 motion, arguing that his attorney had provided constitutionally ineffective assistance. At an evidentiary hearing, both Jae and his lawyer testified that “deportation was the determinative issue” to Jae in deciding whether to accept a plea. The attorney acknowledged that although Jae’s defense to the drug charge was really weak, if he had known Jae would be deported upon pleading guilty, he would have advised him to go to trial anyway.

The attorney was dead wrong. Jae was subject to mandatory deportation as a result of the plea. When Jae learned of this consequence, he filed a 2255 motion, arguing that his attorney had provided constitutionally ineffective assistance. At an evidentiary hearing, both Jae and his lawyer testified that “deportation was the determinative issue” to Jae in deciding whether to accept a plea. The attorney acknowledged that although Jae’s defense to the drug charge was really weak, if he had known Jae would be deported upon pleading guilty, he would have advised him to go to trial anyway.

The district court denied the 2255, holding that while Jae Lee’s counsel had performed deficiently, Jae could not show that he was prejudiced by his attorney’s erroneous advice. The 6th Circuit agreed.

Today, the Supreme Court reversed, 6-2, in a substantial victory for Jae. The Supremes noted that the basic rule since Hill v. Lockhart has been that when a defendant claims his counsel’s deficient performance deprived him of a trial by causing him to accept a plea, the defendant can show prejudice by demonstrating a “reasonable probability that, but for counsel’s errors, he would not have pleaded guilty and would have insisted on going to trial.”

The problem with Government’s per se rule that a defendant without a viable defense cannot show prejudice from the denial of his right to trial, Chief Justice Roberts wrote, is that “categorical rules are ill suited to an inquiry that demands a case-by-case examination of the totality of the evidence.” What’s more, the Government overlooks that the Hill v. Lockhart inquiry focuses on a defendant’s decisionmaking, which may not turn solely on the likelihood of conviction after trial.

The Court said the decision whether to plead guilty involves assessing the respective consequences of a conviction after trial and by plea. When those consequences are, from the defendant’s perspective, similarly dire, even the smallest chance of success at trial may look attractive. For Jae, deportation after some time in prison was not meaningfully different from deportation after somewhat less time; he says he accordingly would have rejected any plea leading to deportation in favor of throwing a “Hail Mary” at trial.

The Court said the decision whether to plead guilty involves assessing the respective consequences of a conviction after trial and by plea. When those consequences are, from the defendant’s perspective, similarly dire, even the smallest chance of success at trial may look attractive. For Jae, deportation after some time in prison was not meaningfully different from deportation after somewhat less time; he says he accordingly would have rejected any plea leading to deportation in favor of throwing a “Hail Mary” at trial.

The Government argued that “a defendant has no entitlement to the luck of a lawless decisionmaker,” quoting Strickland v. Washington. The Court said that the “lawless” quote was made in the context of discussing the presumption of reliability applied to judicial proceedings, which has no place where, as here, a defendant was deprived of a proceeding altogether. When the inquiry is focused on what an individual defendant would have done, the possibility of even a highly improbable result may be pertinent.

The Supreme Court said that district courts should not upset a plea solely because of after-the-fact assertions by a defendant about how he would have pleaded but for his attorney’s deficiencies. Rather, they should look to contemporaneous evidence to substantiate a defendant’s expressed preferences. Here, Jae has adequately demonstrated a reasonable probability that he would have rejected the plea had he known that it would lead to mandatory deportation.

The Government argued that Lee cannot “convince the court that a decision to reject the plea bargain would have been rational under the circumstances, since deportation would almost certainly result from a trial. But the Chief Justice was not willing to let courts decide that “that it would be irrational for some-one in Lee’s position to risk additional prison time in exchange for holding on to some chance of avoiding deportation.”

We think this decision will have a significant effect on 2255 petitioners seeking to set aside an incompetently-advised plea.

Lee v. United States, Case No. 16-327

– Thomas L. Root

Glen filed a petition under

Glen filed a petition under