We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

We had a lot of short notes included in yesterday’s newsletter to federal inmates. We’re publishing those posts below.

10TH CIRCUIT DECLARES SUPERVISED RELEASE REVOCATION STATUTE UNCONSTITUTIONAL

The supervised release statute, 18 USC § 3583, provide that if a person on supervision violates, the court may send him or her back to prison for a specified term, and then impose more supervised release. The maximum terms of reimprisonment authorized by the statute for an supervised release violation of are limited based on the severity of the original crime of conviction, not the conduct that resulted in the revocation.

However, 18 USC § 3583(k) provides an exception. If the person subject to supervised release is a sex offender, and the conduct resulting in the revocation is a specified sex offense, the court is required to “revoke the term of supervised release and require the defendant to serve a term of imprisonment… [for] not less than 5 years.”

Last Thursday, the 10th Circuit ruled that 3583(k) violated Apprendi v. New Jersey and Alleyne v. United States, in that a mandatory prison sentence was increased based on a judge’s finding of fact instead of a jury finding beyond a reasonable doubt. The Court said § 3583(k) “strips the sentencing judge of discretion to impose punishment within the statutorily prescribed range, and… imposes heightened punishment on sex offenders expressly based, not on their original crimes of conviction, but on new conduct for which they have not been convicted by a jury beyond a reasonable doubt and for which they may be separately charged, convicted, and punished.

United States v. Haymond, Case No. 16-5156 (10th Cir., Aug. 31, 2017)

MESSY FOIA REQUEST DOES NOT MERIT DISMISSAL

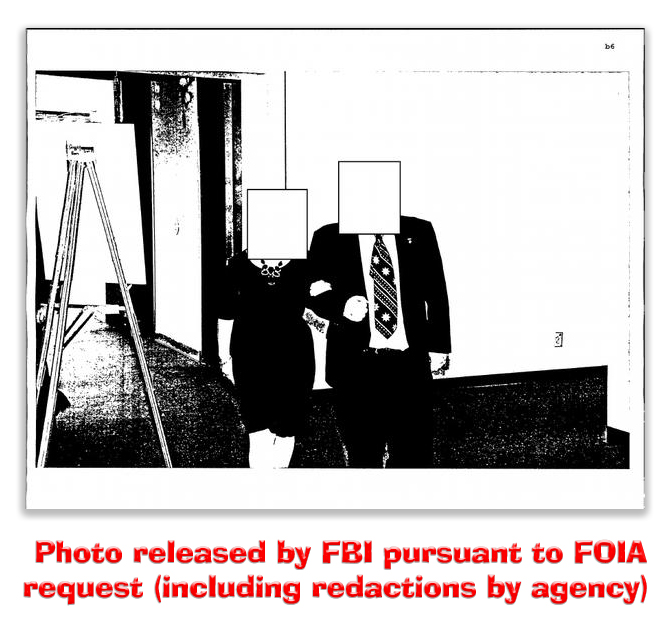

Inmates are notorious for filing badly-written Freedom of Information Act requests. It’s surprising however, to see a lawyer file a request as convoluted as the one attorney Steve Yagman sent to the CIA.

Steve asked for “records/information” on “the names and company/organization affiliations of any CIA employees, agents, operatives, contractors, mercenaries, and/or companies who are alleged to have engaged in torture of persons.” Specifically, he wanted the names and affiliations of those “as to whom President Obama stated that ‘we tortured some folks’ on August 1, 2014: that is, who are the individuals whom the word ‘we’ refers to?”

The CIA wrote Steve back, explaining correctly that FOIA does not require agencies to answer questions. The agency invited Steve to rewrite his request. Steve did not, but instead sued. The district court ruled Steve’s letter did not constitute a request for records, and thus that he had not exhausted administrative remedies. For that reason, the district court said, it lacked subject-matter jurisdiction to hear the case.

The CIA wrote Steve back, explaining correctly that FOIA does not require agencies to answer questions. The agency invited Steve to rewrite his request. Steve did not, but instead sued. The district court ruled Steve’s letter did not constitute a request for records, and thus that he had not exhausted administrative remedies. For that reason, the district court said, it lacked subject-matter jurisdiction to hear the case.

Last week, the 9th Circuit reversed. The Court ruled that because the goal of the FOIA was to provide government information to ordinary citizens, FOIA requests from citizens had to be construed liberally. Sure, Steve’s request was a hot mess, but the Court said Steve’s failure to reasonably describe the records he wanted went to the merits of his claim, and was not a jurisdictional issue.

The Circuit rejected the argument that the request had to reasonably describe the records sought to satisfy “exhaustion and exhaustion itself is jurisdictional,” the Circuit said, “we reject that argument as well. Significantly, FOIA does not expressly require exhaustion, much less label it jurisdictional, nor does FOIA include exhaustion in its jurisdiction-granting provision… Therefore, exhaustion cannot be considered a jurisdictional requirement.”

Yagman v. CIA, Case No. 15-55442 (9th Cir., Aug, 28, 2017)

CALIFORNIA PWITD OFFENSE NOT CATEGORICAL, BUT NOT DRUG FELONY, EITHER

The enhancements on the catch-all federal drug offense, 21 USC § 841(b), are tough: any prior state “felony drug offense” can double the mandatory minimum, or even pop it up to life. The term “felony drug offense” is defined in 21 USC § 802(44) as “an offense that is punishable by imprisonment for more than one year… that prohibits or restricts conduct relating to narcotic drugs, marihuana, anabolic steroids, or depressant or stimulant substances.”

Luis Ocampo-Estrada had a prior conviction under Cal. Health & Safety Code 11378, a drug trafficking offense. California law makes the particular illegal drug an element of the offense, and federal courts used the modified categorical approach to determine whether the crime fits within the “felony drug offense” definition.

The documents filed by the government showed that Luis had pled to an 11378 offense, but did not specify exactly what kind of drug was the basis for the conviction. The government has the burden to prove a prior conviction qualifies as a felony drug offense, but here offered only the abstract of judgment and the state-court minutes from the pronouncement of judgment, neither of which answered “the central question before us: whether Ocampo pleaded guilty to a controlled-substance element of § 11378, which is encompassed by the federal “felony drug offense” definition…”

The documents filed by the government showed that Luis had pled to an 11378 offense, but did not specify exactly what kind of drug was the basis for the conviction. The government has the burden to prove a prior conviction qualifies as a felony drug offense, but here offered only the abstract of judgment and the state-court minutes from the pronouncement of judgment, neither of which answered “the central question before us: whether Ocampo pleaded guilty to a controlled-substance element of § 11378, which is encompassed by the federal “felony drug offense” definition…”

United States v. Ocampo-Estrada, Case No. 15-50471 (9th Cir., Aug. 29, 2017)

TWO STATE STATUTES GET MATHIS TREATMENT

The 8th Circuit last week ruled that the Wisconsin felony of battery of a law enforcement officer is categorically a crime of violence.

The defendant, Patrick Jones – who had been convicted of being a felon-in-possession of a firearm under 18 USC § 921(g) and the Armed Career Criminal Act, 18 USC 924(e) – argued that the Wisconsin statute’s definition of bodily harm includes “illness,” a person could be convicted under Wisconsin Statute 940.20(2) merely for attempting to give an officer a cold. But the Circuit found that Wisconsin cases provided “no realistic basis to conclude that courts would find such low-level conduct sufficient to support a conviction under the statute.” A theoretical possibility that a state may apply its statute to conduct falling short of violent force is not enough to disqualify a conviction; only a realistic probability will do.

The defendant, Patrick Jones – who had been convicted of being a felon-in-possession of a firearm under 18 USC § 921(g) and the Armed Career Criminal Act, 18 USC 924(e) – argued that the Wisconsin statute’s definition of bodily harm includes “illness,” a person could be convicted under Wisconsin Statute 940.20(2) merely for attempting to give an officer a cold. But the Circuit found that Wisconsin cases provided “no realistic basis to conclude that courts would find such low-level conduct sufficient to support a conviction under the statute.” A theoretical possibility that a state may apply its statute to conduct falling short of violent force is not enough to disqualify a conviction; only a realistic probability will do.

The 8th said “The simple fact that the word “illness” is included in the definition of bodily harm is insufficient to render the statute overbroad.”

Meanwhile, 2,500 miles northwest of Minneapolis, the 9th Circuit sitting in Anchorage, Alaska, heard a case in which Dave Geozos – also sentenced under the ACCA – argued that his conviction for armed robbery in Florida was not a crime of violence. The Circuit agreed, holding first that the fact that a robbery is committed while carrying a gun does not make the offense any more violent, because the gun can remain concealed and unused. As for robbery, while it requires more force “than the force necessary to remove the property from the person. Rather, there must be resistance by the victim that is overcome by the physical force of the offender.” However, the amount of resistance can be minimal.

The 9th held that “neither robbery, armed robbery, nor use of a firearm in the commission of a felony under Florida law is categorically a ‘violent felony’. We recognize that this holding puts us at odds with the Eleventh Circuit, which has held, post-Johnson I, that both Florida robbery and (necessarily) armed robbery are ‘violent felonies’ under the force clause.”

The split could set up a Supreme Court review, if the government decides to push the issue. Meanwhile, prisoners with Florida robbery predicates may start figuring out how to get transferred to a joint in the 9th Circuit.

Jones v. United States, Case No. 16-3458 (8th Cir., Aug. 29, 2017)

United States v. Geozos, Case No. 17-35018 (9th Cir., Aug. 15, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

First, the BOP announced it is closing the USP Thomson Special Management Unit – described by The Marshall Project as sort of a “double solitary” detention unit for violent inmates – after adverse reports have circulated for months about inmate deaths, suicides and reported sexual harassment by staff and against staff..

First, the BOP announced it is closing the USP Thomson Special Management Unit – described by The Marshall Project as sort of a “double solitary” detention unit for violent inmates – after adverse reports have circulated for months about inmate deaths, suicides and reported sexual harassment by staff and against staff.. Second, on February 14, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled that BOP employees cannot sue over the government’s denial of hazard pay benefits in connection with their work during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, on February 14, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled that BOP employees cannot sue over the government’s denial of hazard pay benefits in connection with their work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, the Reason Foundation, which skewered the BOP for reported medical neglect at FCI Aliceville, sued the Bureau under the Freedom of Information Act last week for records about whether women who died at Aliceville and FMC Carswell received adequate medical care.

Third, the Reason Foundation, which skewered the BOP for reported medical neglect at FCI Aliceville, sued the Bureau under the Freedom of Information Act last week for records about whether women who died at Aliceville and FMC Carswell received adequate medical care.