We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THINGS ARE SELDOM WHAT THEY SEEM

Buttercup: Things are seldom what they seem,

Skim milk masquerades as cream;

Highlows pass as patent leathers;

Jackdaws strut in peacock’s feathers.

Captain: Very true,

So they do.

Things are Seldom What They Seem

(duet with Buttercup and Capt. Corcoran)

Gilbert & Sullivan, H.M.S. Pinafore

Gilbert and Sullivan had nothing on federal criminal law since the Supreme Court’s decisions in Mathis v. United States and Descamps v. United States. There was a time that you would have thought it was easy to tell a crime of violence, or to identified a controlled substance offense. As Justice Potter Stewart famously said in Jacobellis v. Ohio (about obscenity, not violence), “I know it when I see it.”

Gilbert and Sullivan had nothing on federal criminal law since the Supreme Court’s decisions in Mathis v. United States and Descamps v. United States. There was a time that you would have thought it was easy to tell a crime of violence, or to identified a controlled substance offense. As Justice Potter Stewart famously said in Jacobellis v. Ohio (about obscenity, not violence), “I know it when I see it.”

But no more. Now, courts must go through countless gyrations, looking at whether statutes are divisible, subject to categorical analysis, or are broader than a never-existed federal common law. Thus, even if a defendant beat his grandmother with a ball bat, the crime might not be violent if the state would have applied the same statute to a defendant who nudged his grandma with a down pillow.

Things are seldom what they seem …

Buttercup: Black sheep dwell in every fold;

All that glitters is not gold;

Storks turn out to be but logs;

Bulls are but inflated frogs.

Captain: So they be,

Frequentlee.

So some crimes are violent, some are not. And some drug offenses are “controlled substance offenses,” and some are not.

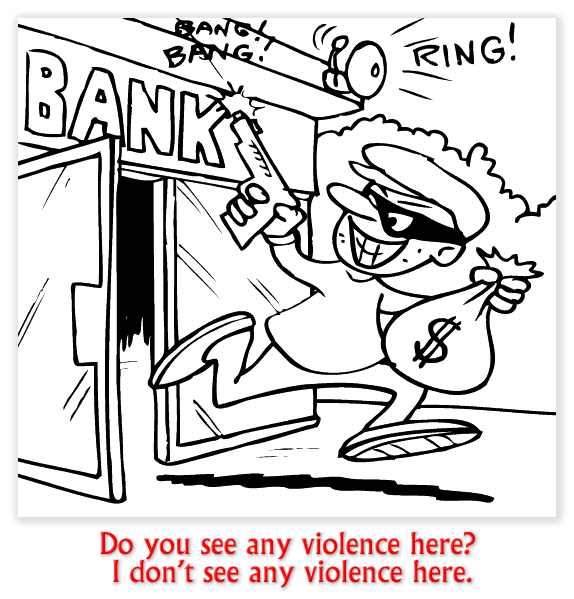

Last week, the 3rd Circuit ruled that Hobbs Act bank robbery by intimidation was met the “elements” test of the career offender Guidelines, and was a crime of violence, regardless of whether it met the enumerated offenses test of the Guidelines (the court suggested it probably did). The Circuit said, “Unarmed bank robbery by intimidation clearly does involve the ‘threatened use of physical force against the person of another’. U.S.S.G. § 4B1.2(a)(1). If a common sense understanding of the word “intimidation” were not enough to prove that, our precedent establishes that § 2113(a)’s prohibition on taking the “property or money or any other thing of value” either “by force and violence, or by intimidation” has as an element the threat of force.”

Last week, the 3rd Circuit ruled that Hobbs Act bank robbery by intimidation was met the “elements” test of the career offender Guidelines, and was a crime of violence, regardless of whether it met the enumerated offenses test of the Guidelines (the court suggested it probably did). The Circuit said, “Unarmed bank robbery by intimidation clearly does involve the ‘threatened use of physical force against the person of another’. U.S.S.G. § 4B1.2(a)(1). If a common sense understanding of the word “intimidation” were not enough to prove that, our precedent establishes that § 2113(a)’s prohibition on taking the “property or money or any other thing of value” either “by force and violence, or by intimidation” has as an element the threat of force.”

Meanwhile, the 1st Circuit refused to apply the Armed Career Criminal Act to a defendant who had a prior conviction for two drug offenses and attempted 2nd-degree armed robbery under New York law. The Circuit held that when the defendant had gotten the New York conviction, New York law applied it to conduct – such as purse-snatching where the victim and perp had a tug-of-war – that fell far short of the violent physical force needed to meet the elements test of the ACCA.

The 4th Circuit concluded that the West Virginia offense of unlawful wounding under § 61-2-9(a) “categorically qualifies as a crime of violence under the force clause, because it applies “only to a defendant who “shoots, stabs, cuts or wounds any person, or by any means causes him or her bodily injury with intent to maim, disfigure, disable or kill.” The Circuit held that the minimum conduct required for conviction of unlawful wounding must at least involve “physical force capable of causing physical injury to another person.” Thus, the offense “squarely matches ACCA’s force clause, which requires force that is capable of causing physical pain or injury.”

The 9th Circuit ruled that a drug conspiracy under the laws of the State of Washington was not a “controlled substance offense” for purposes of Guidelines § 2K2.1(a)(4)(A), because under Washington state law, a defendant could be convicted even if the only other conspirator was an undercover cop. The Circuit held that, as a result, “the Washington drug conspiracy statute covers conduct that would not be covered under federal law, and the Washington drug conspiracy statute is therefore not a categorical match to conspiracy under federal law.”

The 9th Circuit ruled that a drug conspiracy under the laws of the State of Washington was not a “controlled substance offense” for purposes of Guidelines § 2K2.1(a)(4)(A), because under Washington state law, a defendant could be convicted even if the only other conspirator was an undercover cop. The Circuit held that, as a result, “the Washington drug conspiracy statute covers conduct that would not be covered under federal law, and the Washington drug conspiracy statute is therefore not a categorical match to conspiracy under federal law.”

Finally, the 1st Circuit ruled yesterday that a conviction under Massachusett’s assault and battery with a dangerous weapon law (“ABDW”) was not a crime of violence when done recklessly, and concluded that the defendant’s state records, which reported he had attacked someone “with a shod foot,” were not clear enough to show that he was convicted of intentional ABDW instead of the merely reckless kind. Thus, the defendant did not have three prior crimes of violence, and could not be sentenced under the ACCA.

Buttercup: Drops the wind and stops the mill;

Turbot is ambitious brill;

Gild the farthing if you will,

Yet it is a farthing still.

Captain: Yes, I know.

That is so.

United States v. Wilson, Case No. 16-3845 (3rd Cir. Jan. 17, 2018)

United States v. Steed, Case No. 17-1011 (1st Cir. Jan. 12, 2018)

United States v. Covington, Case No. 17-4120 (4th Cir. Jan. 18, 2018)

United States v. Brown, Case No. 16-30218 (9th Cir. Jan. 16, 2018)

United States v. Kennedy, Case No. 15-2298 (1st Cir. Jan. 24, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root

Latroy Burris, convicted of being a felon-in-possession of a gun, was sentenced under the ACCA for priors of drug distribution, robbery and aggravated robbery. He conceded the drug conviction counted for ACCA purposes, and the 5th Circuit last year said aggravated robbery was a crime of violence. But Latroy argued that Texas robbery under § 29.02(a) of the Texas Penal Code was not a crime of violence.

Latroy Burris, convicted of being a felon-in-possession of a gun, was sentenced under the ACCA for priors of drug distribution, robbery and aggravated robbery. He conceded the drug conviction counted for ACCA purposes, and the 5th Circuit last year said aggravated robbery was a crime of violence. But Latroy argued that Texas robbery under § 29.02(a) of the Texas Penal Code was not a crime of violence.