We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

CIRCUITS BUSY SHUTTING DOWN 924(C) DIMAYA CLAIMS

In the wake of Sessions v. Dimaya, a lot of people doing time for using or carrying a gun during a crime of violence have hoped to attack their 18 USC 924(c) convictions by arguing the underlying crime was not violent. Two courts of appeals – the most recent one last week – are making that pretty hard. A third circuit may be on the way there.

In the wake of Sessions v. Dimaya, a lot of people doing time for using or carrying a gun during a crime of violence have hoped to attack their 18 USC 924(c) convictions by arguing the underlying crime was not violent. Two courts of appeals – the most recent one last week – are making that pretty hard. A third circuit may be on the way there.

Section 924(c) makes it punishable by a minimum five-year consecutive sentence, to use, carry, or possess a firearm in connection with a “crime of violence.” The “residual clause” of 924(c) defines “crime of violence” to mean a felony “that by its nature, involves a substantial risk that physical force against the person or property of another may be used in the course of committing the offense.” In Johnson v. United States and, later, in Dimaya, the Supreme Court invalidated similar residual clauses, because what might or might not constitute a “substantial risk” was so vague that a reasonable person was unable to determine beforehand what the legal effect of conduct would be. For example, while murder certainly carried a substantial risk that physical force may be used against the victim, how about drunk driving (which, if it were the defendant’s fourth or tenth offense – depending on the state – might be a felony)?

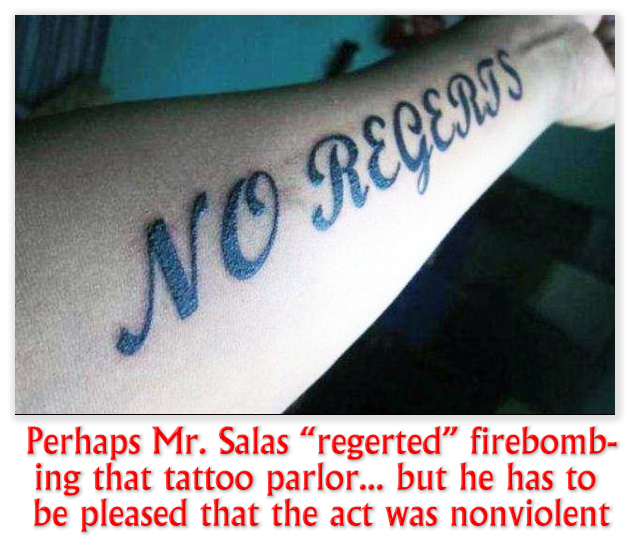

Due to Johnson and Dimaya, all manner of offenses that may sound like they’re violent have been held not to be “crimes of violence.”

Irma Ovalles, convicted of being part of a carjacking crew that used baseball bats and assault rifles, filed a 2255 motion challenging her 924(c) conviction on the grounds that carjacking in its ordinarily sense is not a crime of violence. Last week, the 11th Circuit handed down a ruling that all but dooms her effort.

To determine whether a prior offense is a “crime of violence,” which is what Johnson and Dimaya address, a court is to use a “categorical approach,” which requires a reviewing court not to look at what the defendant actually did to, for example, assault a police officer in, say, Tennessee. Instead, the court is to ‘imagine’ an “idealized ordinary case of the crime,” and figure out whether it could be done without using violent physical force. Sure punching a cop would use violent physical force. But what if the defendant spit on the police officer instead? If Tennessee state law would permit prosecuting such an act, would that – disgusting though it might be – be held not to be “violent physical force?” If so, the predicate crime is not a “crime of violence.”

To determine whether a prior offense is a “crime of violence,” which is what Johnson and Dimaya address, a court is to use a “categorical approach,” which requires a reviewing court not to look at what the defendant actually did to, for example, assault a police officer in, say, Tennessee. Instead, the court is to ‘imagine’ an “idealized ordinary case of the crime,” and figure out whether it could be done without using violent physical force. Sure punching a cop would use violent physical force. But what if the defendant spit on the police officer instead? If Tennessee state law would permit prosecuting such an act, would that – disgusting though it might be – be held not to be “violent physical force?” If so, the predicate crime is not a “crime of violence.”

So assume the defendant were packing a gun hidden in her waistband while assaulting the officer? Or pulled the gun and pistol-whipped him? Would the fact that she reasonably been prosecuted for spitting on him instead mean that the crime was not violent, and thus render the 924(c) residual clause impermissibly vague?

The 11th Circuit cleanly cut the “categorical approach” Gordian knot. “On the flip side,” the Court said, “Johnson and Dimaya also make clear… that if 924(c)(3)’s residual clause is instead interpreted to incorporate what we’ll call a conduct-based approach to the crime-of-violence determination, then the provision is not unconstitutionally vague.” Unlike the categorical approach, the conduct-based approach does not focus on legal definitions and “hypothetical ordinary case,” but instead looks at how the defendant actually committed the underlying crime. The 11th held that where the crime of violence being weighed is not a prior offense, but instead a contemporaneous one (and you cannot commit a 924(c) offense without simultaneously committing a crime of violence or drug trafficking offense), then the conduct-based approach had to be used under the rule of “constitutional doubt.” The rule of “constitutional doubt” holds that any reasonable construction available must be used in order to save a statute from unconstitutionality. “Accordingly,” the Circuit ruled, “we hold that 924(c)(3)(B) prescribes a conduct-based approach, pursuant to which the crime-of-violence determination should be made by reference to the actual facts and circumstances underlying a defendant’s offense.”

The 11th Circuit cleanly cut the “categorical approach” Gordian knot. “On the flip side,” the Court said, “Johnson and Dimaya also make clear… that if 924(c)(3)’s residual clause is instead interpreted to incorporate what we’ll call a conduct-based approach to the crime-of-violence determination, then the provision is not unconstitutionally vague.” Unlike the categorical approach, the conduct-based approach does not focus on legal definitions and “hypothetical ordinary case,” but instead looks at how the defendant actually committed the underlying crime. The 11th held that where the crime of violence being weighed is not a prior offense, but instead a contemporaneous one (and you cannot commit a 924(c) offense without simultaneously committing a crime of violence or drug trafficking offense), then the conduct-based approach had to be used under the rule of “constitutional doubt.” The rule of “constitutional doubt” holds that any reasonable construction available must be used in order to save a statute from unconstitutionality. “Accordingly,” the Circuit ruled, “we hold that 924(c)(3)(B) prescribes a conduct-based approach, pursuant to which the crime-of-violence determination should be made by reference to the actual facts and circumstances underlying a defendant’s offense.”

Under the conduct-based approach, Irma is clearly going to be in deep trouble when her case gets back to the district court. As one 11th Circuit judge asked in his concurring opinion, “How did we ever reach the point where this Court, sitting en banc, must debate whether a carjacking in which an assailant struck a 13-year-old girl in the mouth with a baseball bat and a cohort fired an AK-47 at her family is a crime of violence? It’s nuts.”

The 4th Circuit just last month heard en banc arguments in United States v. Simms, which may go the same way as Barrett and Ovalles.

Ovalles v. United States, Case No. 17-10172 (11th Cir., Oct. 4, 2018)

United States v. Barrett, Case No. 14-2641 (2nd Cir., Sept. 10, 2018)

United States v. Simms, Case No. 15-4640 (4th Cir., decision pending)

– Thomas L. Root