We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

2-0-1 ON SENTENCING ACTIONS LAST WEEK

Three separate proceedings on sentencing or sentence reduction came to our attention last week, unrelated except for the possibilities they represent.

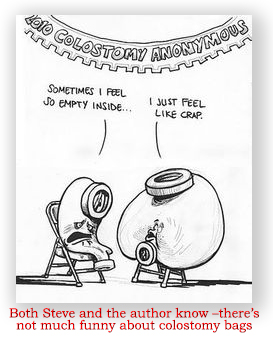

First, Steve Gass asked his court for a compassionate release. While doing 106 months for six bank robberies (Mr. Gass preferred using a note rather than a gun in each of them), Steve was diagnosed with a malignant tumor located in his rectal wall. The tumor was successfully removed, but along with it, he lost his rectum and anus. The procedure left him dependent on a colostomy bag and subject to what the Court euphemistically called “special hygiene requirements” and heightened medical monitoring. (Having had a colostomy bag for six terrible weeks once, I have some sense of those “special” requirements – a gas mask and a gasoline-powered power washer are on the list).

First, Steve Gass asked his court for a compassionate release. While doing 106 months for six bank robberies (Mr. Gass preferred using a note rather than a gun in each of them), Steve was diagnosed with a malignant tumor located in his rectal wall. The tumor was successfully removed, but along with it, he lost his rectum and anus. The procedure left him dependent on a colostomy bag and subject to what the Court euphemistically called “special hygiene requirements” and heightened medical monitoring. (Having had a colostomy bag for six terrible weeks once, I have some sense of those “special” requirements – a gas mask and a gasoline-powered power washer are on the list).

While Steve had beaten the cancer, he argued, his current condition is nevertheless “both serious and difficult to manage in a prison setting, marked neither by enhanced sanitary conditions appropriate for colostomy-dependent patients or heightened monitoring necessary to prevent secondary effects of infection or recurrence of a malignancy.” Clearly, the tumor did not affect Steve’s remarkable capacity for understatement.

The government, being the caring and benevolent organism that it is, argued that Steve had “recovered” from colorectal cancer, so his colostomy condition – which he could and would have to manage for the rest of his life – cannot qualify as the kind of “extraordinary and compelling” reason for a reduction anticipated by 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A)(i).

The district court, recognizing the government’s disingenuous argument for being the same substance that fills Steve’s colostomy bag – ruled that Steve had “shown that his physical and medical condition substantially diminishes his ability to provide self-care within the environment of a correctional facility. And this is not a condition that [he] will ever recover from — he will be device dependent and subject to enhanced hygiene and monitoring requirements for the rest of his life.” The court, with a gift for understatement the equal of Steve’s, thus held that the permanent colostomy was extraordinary and compelling enough.

The district court, recognizing the government’s disingenuous argument for being the same substance that fills Steve’s colostomy bag – ruled that Steve had “shown that his physical and medical condition substantially diminishes his ability to provide self-care within the environment of a correctional facility. And this is not a condition that [he] will ever recover from — he will be device dependent and subject to enhanced hygiene and monitoring requirements for the rest of his life.” The court, with a gift for understatement the equal of Steve’s, thus held that the permanent colostomy was extraordinary and compelling enough.

Still, the court did not shorten Steve’s sentence. Rather, it creatively resentenced Steve to the time remaining on his sentence, but ordered Steve to home confinement for the remaining 28 months or so he had to serve. The decision showcases how the sentence reduction power can be employed with precision to fashion modifications that address the prisoner’s situation without simply letting recipients out to run amok

* * *

In the 6th Circuit, Dave Warren got a statutory maximum 120-month sentence for being a felon in possession of a gun in violation of 18 USC § 922(g)(1). Both he and the government sought a sentence somewhere within his 51-63 month Guidelines range. But the judge was convinced that Dave’s criminal history made him “a high risk offender… an individual that must be deterred. 51 to 63 months… considering the danger this individual poses to the community, is nowhere in my view close to what is required.”

In the 6th Circuit, Dave Warren got a statutory maximum 120-month sentence for being a felon in possession of a gun in violation of 18 USC § 922(g)(1). Both he and the government sought a sentence somewhere within his 51-63 month Guidelines range. But the judge was convinced that Dave’s criminal history made him “a high risk offender… an individual that must be deterred. 51 to 63 months… considering the danger this individual poses to the community, is nowhere in my view close to what is required.”

Last week, the 6th Circuit reversed the sentence. The appeals court noted that “because the Guidelines already account for a defendant’s criminal history, imposing an extreme variance based on that same criminal history is inconsistent with the need to avoid unwarranted sentence disparities among defendants with similar records who have been found guilty of similar conduct…”

“We do not mean to imply that only a sentence in or around that range will avoid disparities with other similar defendants,” the Court wrote. “But we do not see how the sentence imposed here avoids them.” Because the district court’s discussion of whether its 120-month sentence avoided unwarranted sentencing disparities depended only on criminal history factors already addressed by the Guidelines, the 6th said, the district court relied “on a problem common to all” defendants within the same criminal history category Dave fell into – that is, that they all have an extensive criminal history – and thus did not provide “a sufficiently compelling reason to justify imposing the greatest possible deviation from the Guidelines-recommended sentence in this case.”

* * *

Finally, I recently reported on a remarkable “Holloway”-type motion in Chad Marks’ case. Chad was convicted of a couple of bank robberies, but unlike Steve Gass, Chad did carry a gun. Under 18 USC § 924(c), using or carrying a gun during a crime of violence or drug deal adds a mandatory five years onto your sentence. If you are convicted of a second 924(c) offense, the minimum additional sentence is 25 years. Unfortunately, the statute was poorly written, so that if you carry a gun to a bank robbery on Monday, and then do it again on Tuesday, you will be sentenced for the robberies, and then have a mandatory 30 years added to the end of the sentence, five years for Monday’s gun, and 25 years for Tuesday’s gun.

Finally, I recently reported on a remarkable “Holloway”-type motion in Chad Marks’ case. Chad was convicted of a couple of bank robberies, but unlike Steve Gass, Chad did carry a gun. Under 18 USC § 924(c), using or carrying a gun during a crime of violence or drug deal adds a mandatory five years onto your sentence. If you are convicted of a second 924(c) offense, the minimum additional sentence is 25 years. Unfortunately, the statute was poorly written, so that if you carry a gun to a bank robbery on Monday, and then do it again on Tuesday, you will be sentenced for the robberies, and then have a mandatory 30 years added to the end of the sentence, five years for Monday’s gun, and 25 years for Tuesday’s gun.

Congress always meant that the second offense’s 25 years should apply only after conviction for the first one, but it did not get around to fixing the statute until last year’s First Step Act adopted Sec. 403. But to satisfy the troglodytes in the Senate (yes, Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Arkansas, I mean you), the change the law was not made retroactive.

Chad has served 20 years, during which time he has gone from a nihilistic young miscreant to a college-educated inmate teacher and mentor. The federal judge who sentenced Chad 20 years ago recognizes that post-conviction procedure is so restricted that the court can do nothing, but he asked in an order that the U.S. Attorney “carefully consider exercising his discretion to agree to an order vacating one of Marks’ two Section 924(c) convictions. This would eliminate the mandatory 25-year term that is now contrary to the present provisions of the statute.”

Chad has served 20 years, during which time he has gone from a nihilistic young miscreant to a college-educated inmate teacher and mentor. The federal judge who sentenced Chad 20 years ago recognizes that post-conviction procedure is so restricted that the court can do nothing, but he asked in an order that the U.S. Attorney “carefully consider exercising his discretion to agree to an order vacating one of Marks’ two Section 924(c) convictions. This would eliminate the mandatory 25-year term that is now contrary to the present provisions of the statute.”

Since then, Chad Marks’ appointed counsel has filed a lengthy recitation of the defendant’s extraordinary BOP record. Despite this, and despite the fact that over two months have elapsed since the judge’s request to the U.S. Attorney, the government has not seen fit to say as much as one word about the matter.

Order, United States v. Gass, Case No. 10-60125-CR (SDFL Apr. 30, 2019)

United States v. Warren, 2019 U.S. App. LEXIS 14005 (6th Cir. May 10, 2019)

Order, United States v. Marks, Case No. 03-cr-6033 (WDNY, Mar. 14, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root