We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

3RD CIRCUIT GOES OFF THE RAILS ON ADMINISTRATIVE EXHAUSTION

Francis Raia, a small-time Hoboken politician who tried to buy a city council seat for $50 a vote, ended up with a conviction for fraud and a very short 90-day sentence (which the government has appealed). Even a few months seemed like a lifetime to Frank, and – given the coronavirus – it might just be. So he asked his district court for compassionate release.

The district court said it would grant the motion, except that the case had been appealed by the government so it had no jurisdiction. Raia’s lawyers, rather than appealing the District Court’s decision, instead refiled the § 3582 motion with the 3rd Circuit to grant compassionate release, a truly foolish approach. (Appeals courts are for appeals, but that is an issue for another day).

The district court said it would grant the motion, except that the case had been appealed by the government so it had no jurisdiction. Raia’s lawyers, rather than appealing the District Court’s decision, instead refiled the § 3582 motion with the 3rd Circuit to grant compassionate release, a truly foolish approach. (Appeals courts are for appeals, but that is an issue for another day).

Last week, the 3rd refused to grant Frank’s motion for several reasons, any of which would have been good enough by itself. But just to show it could be as foolish as the lawyers appearing before it, the Circuit then laid down some dictum on an issue that had not been briefed. The three-judge panel essentially gutted well-established exceptions to the administrative exhaustion doctrine in the process.

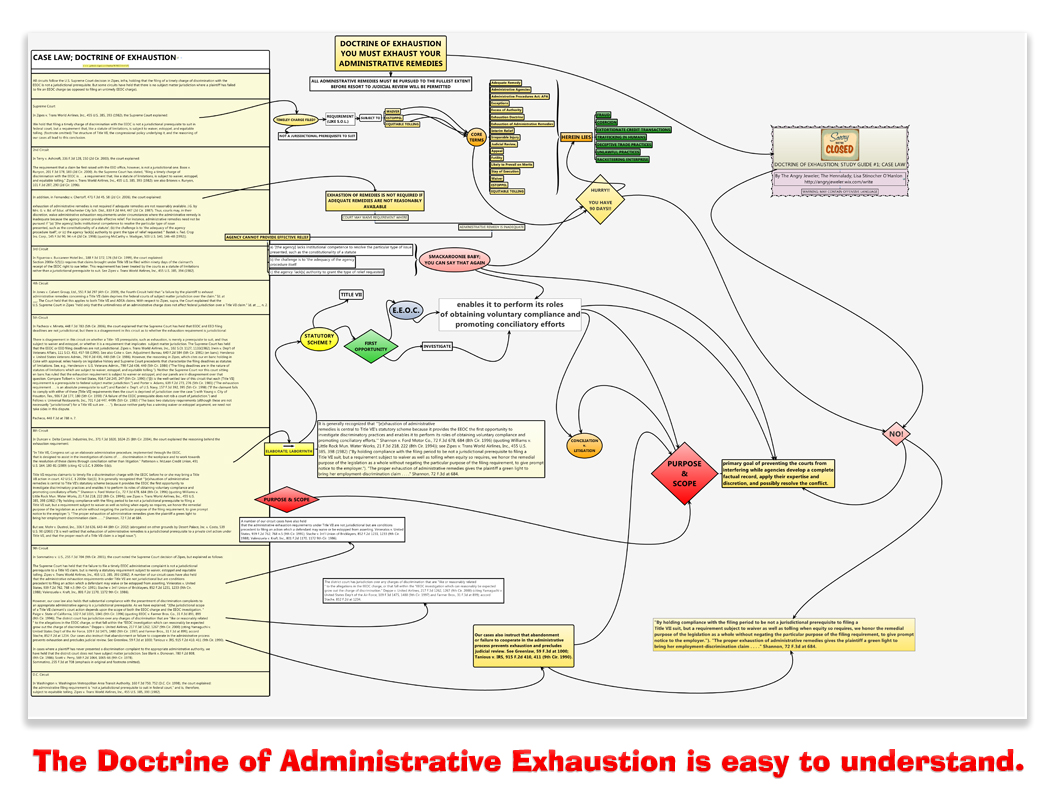

Exhaustion means that an inmate has to complete the administrative review process before he or she goes to court. The compassionate-release statute, 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A), requires that an inmate first ask the warden to recommend compassionate release, and exhaust remedies if denied. If the warden does nothing, the inmate can file directly with the court after 30 days.

There are some well-established exceptions to exhaustion. If exhaustion would be futile, if there are exigent circumstances, if the agency has already made clear that it will deny the request: all of these have excused exhaustion requirements in cases. Frank apparently did not ask the BOP for its recommendation first, but the district court never addressed that lapse, and on appeal, neither party discussed the exhaustion requirement (or Frank’s failure to meet it) in the briefs.

There are some well-established exceptions to exhaustion. If exhaustion would be futile, if there are exigent circumstances, if the agency has already made clear that it will deny the request: all of these have excused exhaustion requirements in cases. Frank apparently did not ask the BOP for its recommendation first, but the district court never addressed that lapse, and on appeal, neither party discussed the exhaustion requirement (or Frank’s failure to meet it) in the briefs.

But the 3rd weighed in nonetheless. After paying lip service to the risks of COVID-19 to federal prison inmates like Raia, the three-judge panel said

But the mere existence of COVID-19 in society and the possibility that it may spread to a particular prison alone cannot independently justify compassionate release, especially considering BOP’s statutory role, and its extensive and professional efforts to curtail the virus’s spread. See generally Federal Bureau of Prisons, COVID19 Action Plan (Mar. 13, 2020, 3:09 PM). Given BOP’s shared desire for a safe and healthy prison environment, we conclude that strict compliance with § 3582(c)(1)(A)’s exhaustion requirement takes on added — and critical — importance. And given the Attorney General’s directive that BOP “prioritize the use of [its] various statutory authorities to grant home confinement for inmates seeking transfer in connection with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic,” we anticipate that the exhaustion requirement will be speedily dispatched in cases like this one.

BOP’s action plan? How’s that working out? The BOP sends COs back to work after being exposed to an inmate with COVID-19 who later died, The BOP fudges the numbers. The BOP denies any problems with halfway houses. Strong arguments exist that the BOP’s approach to COVID-19 has been ham-handed.

That is hardly the only problem with the slapdash decision. The Circuit held that before defendants file a motion in court for compassionate release under § 3582(c)(1)(A), they “must ask the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to do so on their behalf, give BOP thirty days to respond, and exhaust any available administrative appeals. See § 3582(c)(1)(A).”

That is hardly the only problem with the slapdash decision. The Circuit held that before defendants file a motion in court for compassionate release under § 3582(c)(1)(A), they “must ask the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to do so on their behalf, give BOP thirty days to respond, and exhaust any available administrative appeals. See § 3582(c)(1)(A).”

Yesterday, Raia’s attorneys filed a motion for clarification with the 3rd Circuit, asking that the court at least correct that holding to require defendants to exhaust remedies or wait 30 days, but not both. The government does not oppose the motion, which argues that

It is critically important that the Court’s opinion be clear on § 3582(c)(1)(A)’s requirements. As the Court recognized, COVID-19 poses serious risks within the federal prison system, particularly to high-risk inmates such as Mr. Raia. Now more than ever, individualized determinations of compassionate release must be made as expeditiously as the law permits. Any suggestion that defendants must both wait thirty days and exhaust administrative appeals will inevitably lead to confusion among the district courts and delays in adjudicating properly filed compassionate-release motions, potentially with life-or-death consequences.

Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman argued last Saturday in his Sentencing Law and Policy blog that the Circuit’s ruling “creates the problematic impression that “30-day lapsing/exhaustion” language in 18 U.S.C. § 3582(c)(1)(A) is tantamount to a jurisdictional bar to the granting of a sentence reduction motion. But the language and structure of this requirement makes it appear much more like what the Supreme Court calls ‘nonjurisdictional claim-processing rules’… With COVID-19 making every day matter, this is a critically important distinction because claim-processing rules can be forfeited if not raised by a party and might be subject to equitable exceptions. In other words, if and when the ‘30-day lapsing/exhaustion’ language is properly understood by courts as a claim-processing rules, then courts can… decide that the requirement need not be meet given the equities of a particular case.”

Berman rightly notes that “sentence reduction motions under § 3582(c)(1)(A) have become hugely important in the coronavirus world of federal sentencing. As SDNY Chief Judge Coleen McMahon astutely stated this week in US v. Resnik, No. 1:12-cr-00152-CM (SDNY Apr. 2, 2020) ‘releasing a prisoner who is for all practical purposes deserving of compassionate release during normal times is all but mandated in the age of COVID-19’.”

Berman rightly notes that “sentence reduction motions under § 3582(c)(1)(A) have become hugely important in the coronavirus world of federal sentencing. As SDNY Chief Judge Coleen McMahon astutely stated this week in US v. Resnik, No. 1:12-cr-00152-CM (SDNY Apr. 2, 2020) ‘releasing a prisoner who is for all practical purposes deserving of compassionate release during normal times is all but mandated in the age of COVID-19’.”

This is an awful decision, and what’s worse, an unnecessary one. The Court has already denied the appeal when it adds its “oh, by the way,” that the defendant had not exhausted administrative remedies (and does so in a misstatement of the statute that would earn a first-year law student a failing grade).

My belief that the Raia decision is an intellectual “drive-by shooting” of established administrative exhaustion waiver law is shared by others. In the New Jersey Law Journal, Christopher Adams, chairman of the criminal defense and regulatory practice group at Greenbaum, Rowe, Smith & Davis in Woodbridge, New Jersey, observed that prisoners may be able to sidestep § 3582(c)(1)’s 30-day requirement based on vulnerability to the coronavirus, because Raia fails to address a 1992 U.S. Supreme Court case, McCarthy v. Madigan, allowing prisoners to bypass administrative procedure based on equitable considerations. The 1992 case found exceptions to the 30-day requirement where such a waiting period would prejudice the subsequent court action, where the administrative process lacks authority to grant adequate relief, and where pursuing the administrative remedy would expose the petitioner to undue prejudice.

“I will continue to make these applications to district court. I would encourage people to try,” the NJLJ quoted Adams as saying. “Raia doesn’t close the door to compassionate relief applications, even when the administrative remedy is not observed. I admit, the circuit, in Raia, makes it much harder, but it doesn’t close the door completely.”

I am glad Raia’s counsel – who screwed this pooch to begin with – at least sought clarification of the ruling. It would be far better to seek a rehearing pointing out to the court that it should withdraw the exhaustion portion of the opinion altogether.

I am glad Raia’s counsel – who screwed this pooch to begin with – at least sought clarification of the ruling. It would be far better to seek a rehearing pointing out to the court that it should withdraw the exhaustion portion of the opinion altogether.

United States v. Raia, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 10582 (3rd Cir. Apr 2, 2020)

Unopposed Motion to Amend Opinion, United States v. Raia (filed Apr 6, 2020)

Sentencing Law and Policy, Misguided dicta from Third Circuit panel on procedural aspects of sentence reduction motions under § 3582(c)(1)(A) (Apr 4)

New Jersey Law Journal, After 3rd Circuit Setback, Defense Lawyers Look for New Path for COVID-19 Compassionate Release (Apr. 6)

– Thomas L. Root