We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

3582 ≠ 2255, 6TH CIRCUIT SAYS

Most of the time, unsavory houseguests nick a towel from the bathroom or a spoon from the silver. Not Lennie Day. While staying at Roy West’s Akron, Ohio, house (the decision says he was “hiding out”), Lennie stole $300,000 in cash and jewelry, a .40-caliber gun, and car keys.

If this had been an Airbnb rental, Lennie would have gotten a flaming’ bad review.

If this had been an Airbnb rental, Lennie would have gotten a flaming’ bad review.

Roy, appalled at Lennie’s poor manners, felt that he should confront his erstwhile guest and upbraid him for his rudeness. So Roy organized a posse of friends, led them to Detroit, and asked them to locate Lennie

so that he could express his unhappiness directly to Lennie. He didn’t find him, but later, Lennie passed away after being perforated by several bullets. Sadly, Roy never got to tell Lennie what a faux pas his guest had committed…

In 2014, Roy was convicted for his participation in what the government labeled a murder-for-hire conspiracy targeting Lennie. He was sentenced to life in prison. His direct appeal and a post-conviction motion under 28 USC § 2255 failed.

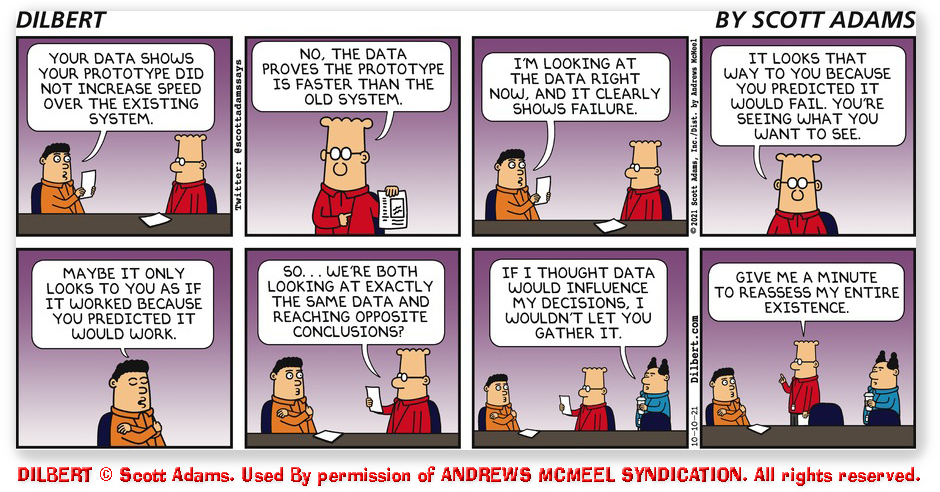

Eight years later, Roy sought compassionate release under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A). He argued that extraordinary and compelling reasons for the reduction included his risk of catching COVID, his rehabilitation, and – raising it for the first time – that his sentence violated Apprendi v New Jersey, a 2000 Supreme Court decision holding that any statutory sentencing enhancement had to be supported by a jury finding the facts supporting the enhancement beyond a reasonable doubt.

Roy claimed that the jury instructions given at his trial did not require the jury to find that death resulted from the conspiracy – a necessary finding for the court to impose a life sentence for the crime.

The district court didn’t bite on the medical risk for COVID, but it did find that the Apprendi error and Roy’s rehabilitation constituted “extraordinary and compelling reasons” to reduce his sentence. It reduced Roy’s sentence to 17 years and cut him loose.

Last week, the 6th Circuit reversed, agreeing with the government that Roy’s § 3582 motion was really a second or successive § 2255 motion in mufti.

The Circuit assumed the district court was right that “a harmful Apprendi violation occurred.” That doesn’t matter, the Circuit said, because “compassionate release cannot ‘provide an end run around habeas.’ The § 2255 procedure “provides a specific, comprehensive statutory scheme for post-conviction relief” and therefore, the 6th ruled, “any attempt to attack a prisoner’s sentence or conviction must abide by its procedural strictures.”

The Circuit assumed the district court was right that “a harmful Apprendi violation occurred.” That doesn’t matter, the Circuit said, because “compassionate release cannot ‘provide an end run around habeas.’ The § 2255 procedure “provides a specific, comprehensive statutory scheme for post-conviction relief” and therefore, the 6th ruled, “any attempt to attack a prisoner’s sentence or conviction must abide by its procedural strictures.”

Once a prisoner has already filed and appealed the denial of a § 2255 motion (as Roy had already done), “relief cannot be obtained in a successive § 2255 motion unless new evidence or a new rule of constitutional law is announced,” the Circuit held. Roy “cannot avoid these restrictions on post-conviction relief by resorting to a request for compassionate release instead.”

Of course, because Apprendi predated Roy’s conviction and – for whatever reason – the error was not raised in his self-written § 2255, there is no way he will be allowed a second § 2255. Roy will just have to do his sentence. For the rest of his natural life.

United States v. West, Case No. 22-2037, 2023 U.S. App. LEXIS 14424 (6th Cir. June 9, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root