We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

ANOTHER CIRCUIT QUESTIONS WHETHER SPEEDY TRIAL ACT VIOLATION SUPPORTS 2255 MOTION

The District of Columbia Circuit has become the latest in a line of courts of appeal to hold that a defendant claiming in a 28 U.S.C. § 2255 motion that his lawyer was ineffective for not raising a Speedy Trial Act issue faces a nearly impossible task of showing he was prejudiced by the error.

Juan McClendon was convicted after a marathon case lasting over four years and four separate trials. He filed a § 2255 petition complaining that his lawyer was ineffective for not filing a Speedy Trial Act motion.

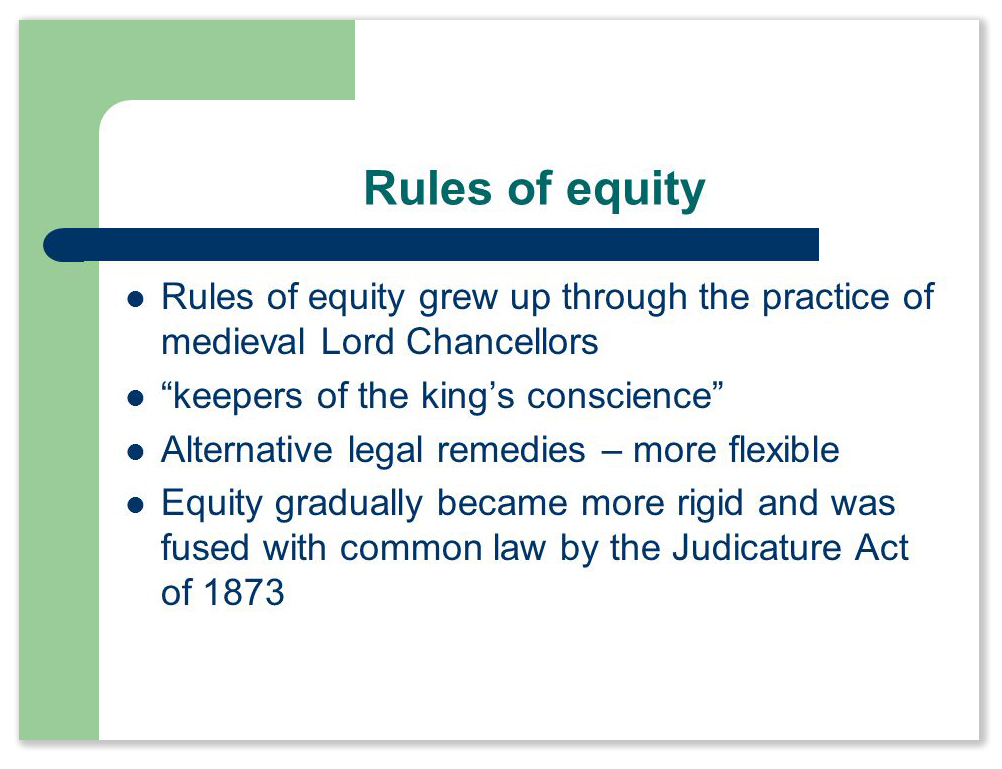

If an STA motion is successful, the trial court must dismiss the indictment, but may do so with or without prejudice. “Without prejudice,” of course, means that the government is free to reindict, which it almost always does.

Juan argued that his lawyer should have raised the STA and gotten a dismissed without prejudice, because the government might not have sought a new indictment. The district court disagreed, and denied Juan’s § 2255 motion.

Last week, the D.C. Circuit agreed, holding that “under the circumstances of this case, failure to obtain a dismissal without prejudice under the STA does not constitute Strickland prejudice. We acknowledge that a dismissal without prejudice forces the government to reindict the defendant in order to secure a conviction. We acknowledge that the government may not be willing to do so in every case, and circumstances outside of the government’s control may preclude it from doing so. McClendon’s argument does not meet that standard. He fails to recognize that it would be the exceedingly rare case in which a defendant could show a reasonable probability that, absent counsel’s failure to obtain a dismissal without prejudice, the outcome of the criminal prosecution would be different.”

Last week, the D.C. Circuit agreed, holding that “under the circumstances of this case, failure to obtain a dismissal without prejudice under the STA does not constitute Strickland prejudice. We acknowledge that a dismissal without prejudice forces the government to reindict the defendant in order to secure a conviction. We acknowledge that the government may not be willing to do so in every case, and circumstances outside of the government’s control may preclude it from doing so. McClendon’s argument does not meet that standard. He fails to recognize that it would be the exceedingly rare case in which a defendant could show a reasonable probability that, absent counsel’s failure to obtain a dismissal without prejudice, the outcome of the criminal prosecution would be different.”

The decision continues the emasculation of the STA. Five other circuits have handed down similar holdings, the 3rd, 4th, 6th, 10th and 11th.

United States v. McLendon, 2019 U.S. App. LEXIS 36522 (DC Cir. Dec. 10, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root

Jolol Carthorne was sentenced as a Guidelines

Jolol Carthorne was sentenced as a Guidelines