We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

7TH CIRCUIT DOES NOT REQUIRE TILTING AT WINDMILLS

“Tilting at windmills,” taken from Cervantes’ classic “Don Quixote,” is typically used to suggest engaging in an activity that is completely futile.

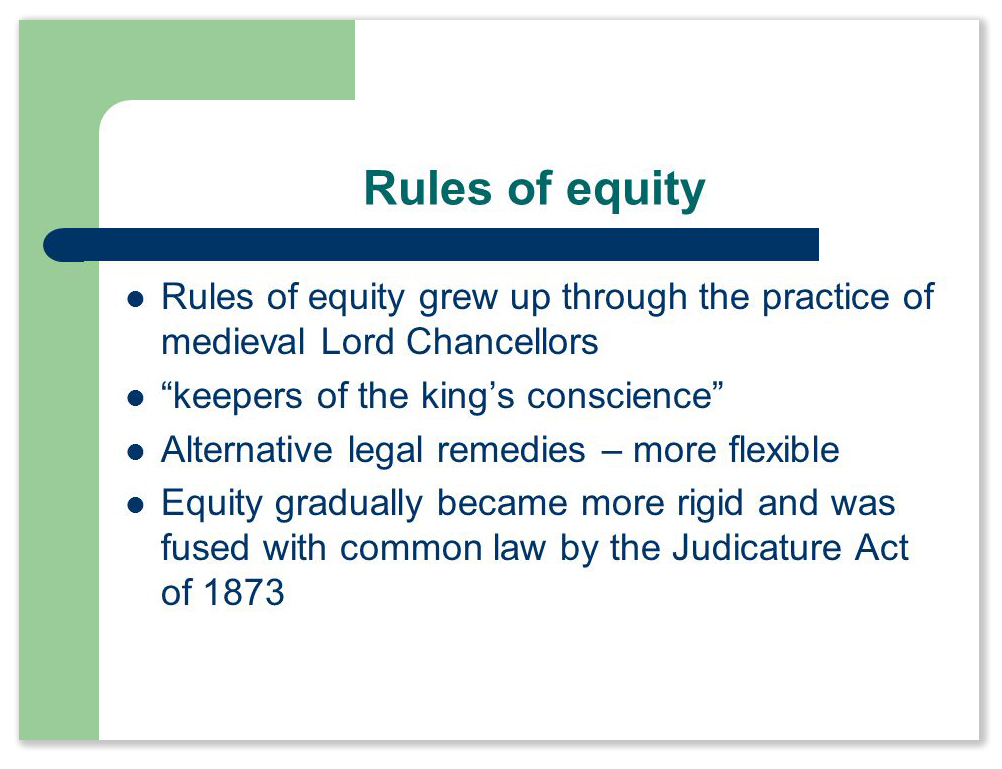

Engaging in a hopeless venture is more common than you think. A lot of post-conviction defendants trying to raise Mathis claims – that prior offenses are not violent or overbroad controlled substance crimes using the categorical approach – have run into a procedural brick wall. Mathis provides procedural guidance on how to interpret statutes. It does not announce a new constitutional rule, and it does not narrow the application of a substantive criminal statute to make prior conduct no longer criminal. People trying to file Mathis § 2255 motions have been frustrated, and people filing § 2241 petitions for habeas corpus have often found the going rough.

Engaging in a hopeless venture is more common than you think. A lot of post-conviction defendants trying to raise Mathis claims – that prior offenses are not violent or overbroad controlled substance crimes using the categorical approach – have run into a procedural brick wall. Mathis provides procedural guidance on how to interpret statutes. It does not announce a new constitutional rule, and it does not narrow the application of a substantive criminal statute to make prior conduct no longer criminal. People trying to file Mathis § 2255 motions have been frustrated, and people filing § 2241 petitions for habeas corpus have often found the going rough.

Last week, the 7th Circuit tackled the issue, ruling that Mathis was “an intervening case of statutory interpretation” that “opens the door to a previously foreclosed claim.” Todd Chazen, who is in a federal prison within the 7th Circuit, filed a petition for habeas corpus under 28 USC § 2241, arguing that under Mathis, his prior conviction for Minnesota third-degree burglary no longer counted for his Armed Career Criminal Act sentence. He was right: under both 7th and 8th Circuit law, the second- and third-degree Minnesota burglary statute had been held to no longer count for ACCA purposes.

The government, however, argued that when Todd filed his § 2255 motion six years ago, he could have made the same argument, even though Mathis had not yet been decided. The Circuit disagreed:

“In 2013—at the time Chazen first moved for post-conviction relief under § 2255—”the law was squarely against” him in that it foreclosed the position he currently advances—that Minnesota burglary is not a violent felony under the Act.

“We also conclude that Mathis can provide the basis for Chazen’s § 2241 petition… Our precedent has focused on whether an intervening case of statutory interpretation opens the door to a previously foreclosed claim. Mathis fits the bill. Mathis injected much-needed clarity and direction into the law under the Armed Career Criminal Act… It is only after Mathis — a case decided after Chazen’s § 2255 petition that the government concedes is retroactive — that courts, including our court and the 8th Circuit, have concluded that Minnesota burglary is indivisible because it lists alternative means of committing a single crime…

“In these circumstances, where the government has conceded that Mathis is retroactive and Chazen was so clearly foreclosed by the law of his circuit of conviction at the time of his original § 2255 petition, we conclude that Chazen has done enough to satisfy the savings clause requirements.”

“In these circumstances, where the government has conceded that Mathis is retroactive and Chazen was so clearly foreclosed by the law of his circuit of conviction at the time of his original § 2255 petition, we conclude that Chazen has done enough to satisfy the savings clause requirements.”

In other words, if the Circuit law is settled, you don’t have to tilt at windmills in your § 2255 motion. If the interpretation of the statute changes later, you can take advantage with a § 2241 petition.

Chazen v. Marske, 2019 U.S.App.LEXIS 27142 (7th Cir. Sept. 9, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root

Jolol Carthorne was sentenced as a Guidelines

Jolol Carthorne was sentenced as a Guidelines