We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

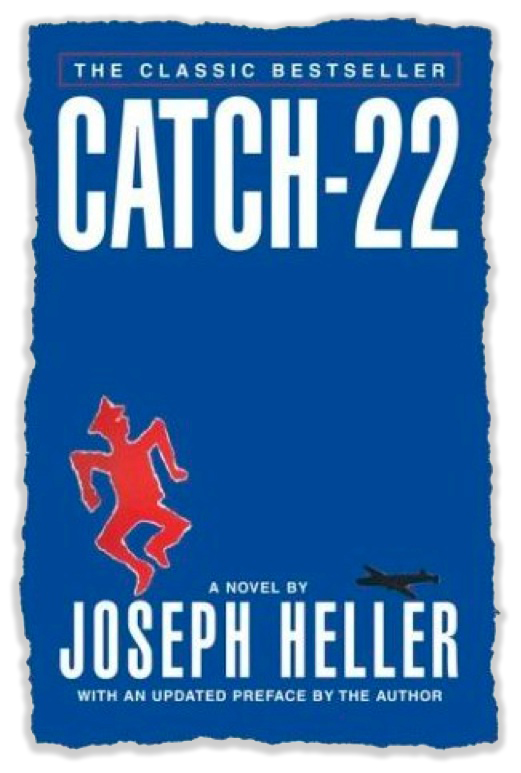

CATCH-22

Those of us approaching social security age lament that the younger among us (and that’s getting to be just about everyone) no longer recalls Joseph Heller’s classic satirical novel about allied bomber pilots in World War II named Catch-22.

Those of us approaching social security age lament that the younger among us (and that’s getting to be just about everyone) no longer recalls Joseph Heller’s classic satirical novel about allied bomber pilots in World War II named Catch-22.

The expression “Catch-22” has since entered the lexicon, referring to a type of unsolvable logic puzzle sometimes called a double bind. According to the novel, people who were crazy were not obligated to fly missions, but anyone who applied to stop flying was showing a rational concern for his safety and was, therefore, sane and had to fly.

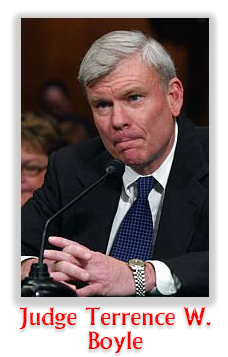

It’s not a perfect analogy, but the 4th Circuit came pretty close to defining a “Catch-22” on Monday. Thilo Brown had been sentenced as a career offender back in the bad old days, when the Guidelines were mandatory. He had been enhanced as a “career offender” for prior crimes of violence, among those being a prior state conviction for resisting arrest. After the Supreme Court held in Johnson v. United States that the residual clause of the Armed Career Criminal Act’s definition of a “crime of violence” was unconstitutionally vague, people who had been sentenced under the ACCA because of priors like Thilo’s won substantial sentence relief.

Thilo’s problem was that he wasn’t sentenced under the ACCA, despite the fact that the “career offender” Guidelines used the identical, word-for-word language defining a “crime of violence” that the Johnson court threw out of the ACCA. But he dutifully filed a post-conviction motion under 28 USC 2255 asking that his “career offender” status be vacated because of Johnson.

The government argued vociferously against Thilo, maintaining that the Guidelines are different that the ACCA, and that the same language that is unconstitutional in one is hunky dory in the other. The Supreme Court took up the question last spring in Beckles v. United States, and agreed that because the Guidelines merely recommended to the judge how to sentence offenders, if they were a little too vague, there’s no harm done.

But the Beckles Court was careful to explain that it was only deciding the case in front of it, in which the prisoner had been sentenced after the Guidelines became advisory in 2005. The Supreme Court said it was not considering whether the vague “crime of violence” language might violate a prisoner’s due process rights if used to sentence someone under the mandatory Guidelines.

So Thilo pursued his 2255 motion, arguing that Johnson is a new right recognized by the Supreme Court which does extend to mandatory Guidelines people like himself. This is an important argument, because Thilo’s 2255 motion fell within the time deadline set out in 28 USC 2255(f)(3) only if it was filed within a year of the right he was asserting being recognized by the Supreme Court, and being made retroactively applicable to cases on collateral review.

So Thilo pursued his 2255 motion, arguing that Johnson is a new right recognized by the Supreme Court which does extend to mandatory Guidelines people like himself. This is an important argument, because Thilo’s 2255 motion fell within the time deadline set out in 28 USC 2255(f)(3) only if it was filed within a year of the right he was asserting being recognized by the Supreme Court, and being made retroactively applicable to cases on collateral review.

Everyone had high hopes for Brown. Countless other lower court cases were stayed awaiting the decision. In fact, a 6th Circuit decision last week cited the pending Brown decision as being the one to resolve the question that went unanswered in Beckles: is the “career offender” residual clause unconstitutional when applied to mandatory Guidelines offenders?

The 4th Circuit has now ruled, and it has dodged the issue slickly. The Circuit, in a 2-1 decision, held that Brown’s 2255 petition was untimely.

The panel said the right under which an inmate proceeds has to be a right recognized by the Supreme Court. This means, the Circuit said, that only the Supreme Court can recognize the right. There is no derivative authority. That is, a lower court cannot recognize a right it may believe is implicit in analogous holdings by the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court recognized in Johnson that the residual clause of the Armed Career Criminal Act was unconstitutionally vague (a due process violation, because everyone has a 5th Amendment right to understand what conduct is or is not unlawful). However, this recognition does not mean that the right was recognized for “career offenders” sentenced under Guidelines using the same language.

The Supreme Court recognized in Johnson that the residual clause of the Armed Career Criminal Act was unconstitutionally vague (a due process violation, because everyone has a 5th Amendment right to understand what conduct is or is not unlawful). However, this recognition does not mean that the right was recognized for “career offenders” sentenced under Guidelines using the same language.

The 4th noted that the Supreme Court said in Beckles that it was not deciding Johnson’s applicability to mandatory Guidelines career offender cases. This merely proved, according to the Brown court, that the Supremes had definitely not yet recognized the right being asserted by Thilo.

Here’s the Catch-22 with the 4th Circuit’s approach. First, accept that no one who has a career offender sentence under the mandatory Guidelines could have possibly been sentenced after 2004, because it would not have been final when United States v. Booker was issued in January 2005, and would have gotten the benefit of a resentencing.

If a “career offender” Guidelines sentence was final on December 31, 2004, a timely 28 USC 2255 motion had to be filed by December 31, 2005. But as of that time, the right to not be sentenced for vague residual-clause offenses was still more than nine years in the future. No 2255 raising the unconstitutionality of the residual clause had any realistic chance of success until the end of June 2015, when Johnson was handed down.

But if the Brown decision is right, in order for such a 2255 to be successful, it had to be timely under 2255(f)(3), because no other subsection would have made such a filing timely.

Except that it could not possibly be timely under (f)(3). The identical “residual clause” language found to be unconstitutional in Johnson could be tested under the advisory Guidelines, because at the time Johnson was decided, people were still being sentenced as career offenders under the Guidelines. Someone could test the language in a 2255 motion filed within a year of finality. But no one could test whether the language remained constitutional if applied to a mandatory Guidelines sentence, because no timely 2255 could be filed challenging its application to a sentence that necessarily had to have been imposed more than nine years before.

Thus, if the 4th Circuit is right in Brown, to assert a constitutional right just recently defined by the Supreme Court, a mandatory Guidelines prisoner would have to have filed the petition challenging it a decade ago, when the right did not exist and he or she would be laughed out of court.

It’s not quite a Catch-22, but it certainly carries the same level of arbitrariness and frustration.

The dissenting judge argued persuasively that the right recognized by the Supreme Court does not have to be the precise application being sought by the petitioner. Instead, alleging a rational and supportable extension of the newly-recognized to a similar fact situation is enough. Certainly, it is more efficient, and is reasonably calculated to do justice.

And should that not count for something?

United States v. Brown, Case No. 16-7056 (4th Cir., August 21, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root