We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

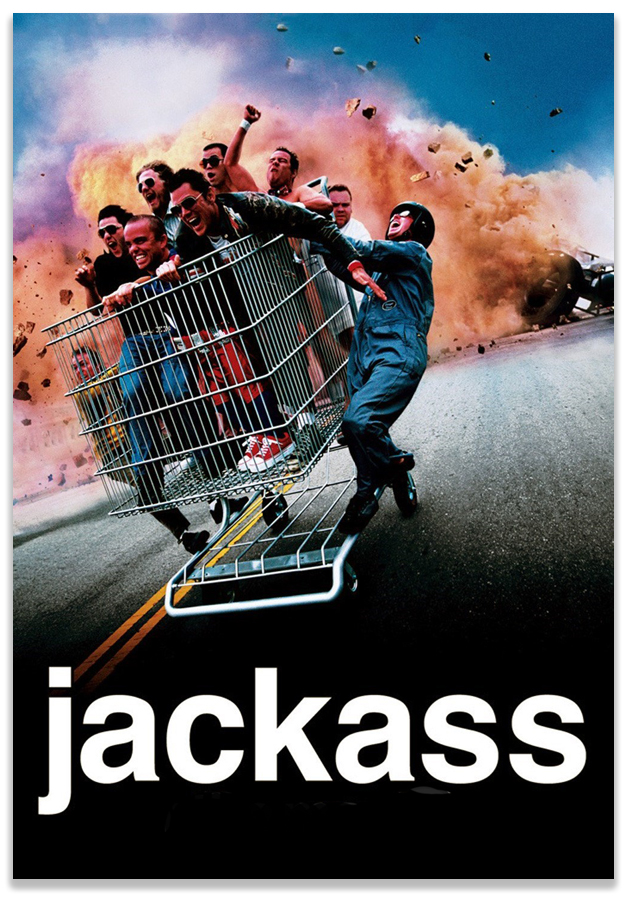

JACKASS

JACKASS

Remember back in 2000 when MTV decided to break Masterpiece Theatre’s hammerlock on classy television programming? The result was Jackass, an ill-conceived piece of televised mayhem in which the show’s participants performed all manner of risky and stupid stunts on themselves and each other. Their viewers – being not just kids but dumb kids – often imitated what they saw on the show.

Remember back in 2000 when MTV decided to break Masterpiece Theatre’s hammerlock on classy television programming? The result was Jackass, an ill-conceived piece of televised mayhem in which the show’s participants performed all manner of risky and stupid stunts on themselves and each other. Their viewers – being not just kids but dumb kids – often imitated what they saw on the show.

Much of what the ensemble cast did to each other – such as branding one participant on his bare kiester with a hot iron – easily blew past negligence and gross negligence standards on the way to sheer recklessness. And that brings us to today’s case.

George Bennett was convicted of being a felon in possession of as gun under 18 USC 922(g), among other crimes. Because the sentencing court concluded that George had three prior “crimes of violence” within the meaning of the Armed Career Criminal Act, he was sentenced under 18 USC 924(e) to 25 years. Without the ACCA specification, the most he could have gotten for the 922(g) was 10 years.

The legal landscape began shifting with the Supreme Court’s decision in Johnson v. United States that a portion of the ACCA – the “residual clause,” which pretty much defined a violent crime as one in which something bad could have happened, intended or not – was unconstitutionally vague. After Johnson, George filed a motion under 28 USC 2255 for relief from the ACCA sentence, arguing that his priors, all of which were aggravated assault under Maine law, were not “crimes of violence” within the meaning of the ACCA.

An ACCA “crime of violence” is an offense that (1) was burglary, arson, extortion or use of explosives (called the “Enumerated Clause”); or (2) has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person of another (called the “Force Clause”).

George argued in his 2255 motion that Maine’s aggravated assault statute went beyond the Force Clause, in that one could commit aggravated assault through reckless conduct but without intent. The district court agreed with George, but the government appealed.

On Wednesday, the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the district court, not necessarily agreeing with George that recklessness was not enough to come within the Force Clause, but not being sure that it did not. In a 54-page exposition of the state of the law on recklessness and the Force Clause, the Circuit concluded that “the text and purpose of ACCA leave us with a ‘grievous ambiguity,’ as to whether ACCA‘s definition of a “violent felony” encompasses aggravated assault in Maine, insofar as that offense may be committed with a mens rea of mere recklessness, as opposed to purpose or knowledge, we… must apply the rule of lenity… and, in consequence, we conclude that Bennett’s two prior Maine convictions for aggravated assault do not so qualify…”

Maine defines aggravated assault to include “intentionally, knowingly or recklessly causing” bodily injury to another. Maine defines the mens rea of recklessness as acting when a person “consciously disregards a risk.”

The problem, the Court said, is that “Congress chose in ACCA to denominate ‘the use of force against another’ as a single, undifferentiated element.” The question thus becomes whether “the relevant volitional act that an offense must have as an element for ACCA purposes is not just the ‘use . . . of physical force,’ but the ‘use . . . of physical force against the person of another.” The injury caused to another by the volitional action in a reckless assault, the Court said, is by definition neither the perpetrator’s object nor a result known to the perpetrator to be practically certain to occur. For that reason, a voluntary reckless act – the Court used the example of throwing a plate against a wall in anger, resulting the splinters flying off and injuring one’s spouse. – may endanger another without deliberately endangering another.

The problem, the Court said, is that “Congress chose in ACCA to denominate ‘the use of force against another’ as a single, undifferentiated element.” The question thus becomes whether “the relevant volitional act that an offense must have as an element for ACCA purposes is not just the ‘use . . . of physical force,’ but the ‘use . . . of physical force against the person of another.” The injury caused to another by the volitional action in a reckless assault, the Court said, is by definition neither the perpetrator’s object nor a result known to the perpetrator to be practically certain to occur. For that reason, a voluntary reckless act – the Court used the example of throwing a plate against a wall in anger, resulting the splinters flying off and injuring one’s spouse. – may endanger another without deliberately endangering another.

The Court could as easily have used the Jackass “branding iron” skit.

The Court traced all of the arguments for and against George’s position, but concluded that “the canon against surplusage does at least suggest that the follow-on ‘against’ phrase in ACCA must be conveying something that the phrase ‘use . . . of physical force’ does not… Nevertheless, we can hardly be sure.”

The Rule of Lenity holds that a court should interpret any ambiguity in a criminal statute in the defendant’s favor. The Circuit said, “We are considering here a sentencing enhancement of great consequence. We should have confidence, therefore, that we are doing Congress’s will in applying this enhancement here.”

The Bennett decision is long but consequential, treating in detail a substantial question on interpreting “use of physical force against the person of another.” The issue may well be the next battleground in ACCA and “crime of violence” litigation.

Bennett v. United States, Case No. 16-2039 (1st Cir., July 5, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root