We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

GOOD INTENTIONS RUN AMOK?

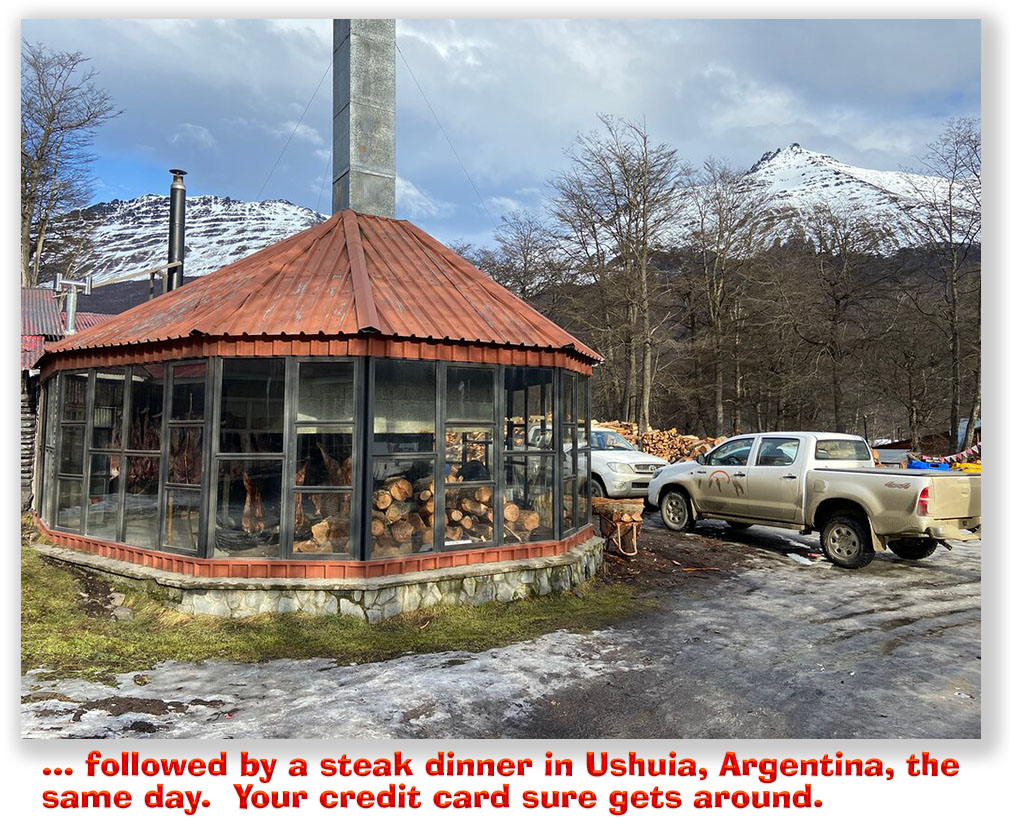

There was a time when the still-nascent Internet was spawning a land-office business in identity theft. Aided by “cyberspace,” hackers, code crackers and slackers had stopped wasting time with all the chatroom yakkers, and instead were using your personally identifiable information (PII) to get new credit cards in your name. Next thing you know, you had bought a 400,000-tenge set of new tires in Almaty, Kazakhstan, the same day you had a 200,000-peso steak dinner in Ushuaia, Argentina.

There was a time when the still-nascent Internet was spawning a land-office business in identity theft. Aided by “cyberspace,” hackers, code crackers and slackers had stopped wasting time with all the chatroom yakkers, and instead were using your personally identifiable information (PII) to get new credit cards in your name. Next thing you know, you had bought a 400,000-tenge set of new tires in Almaty, Kazakhstan, the same day you had a 200,000-peso steak dinner in Ushuaia, Argentina.

This use of an innocent person’s PII to get a bogus line of credit and sticking them with the consequences became known as “identity theft.” And it was perceived as a real problem. Congress responded with 18 USC § 1028A, the “aggravated identify theft” statute.

Just as the government is loathe to ever let a serious crisis go to waste, the Dept of Justice has broadly applied the federal identity theft statute to hammer situations that are nowhere close to the hold that all sorts of misconduct that happens to use someone’s name or personal information in the offense is aggravated identity theft.

The statute imposes a two-year mandatory minimum sentence on any person who, “during and in relation to” certain enumerated felonies, “knowingly transfers, possesses, or uses without lawful authority, a means of identification of another person.” And the government loves offenses with mandatory minimums.

The statute imposes a two-year mandatory minimum sentence on any person who, “during and in relation to” certain enumerated felonies, “knowingly transfers, possesses, or uses without lawful authority, a means of identification of another person.” And the government loves offenses with mandatory minimums.

Today, the brakes may be applied to § 1028A (lucky we have those new tires). SCOTUS will consider the reach of the statute in Dubin v. United States.

Dr. Dubin, the managing partner of a psychological services company that provided mental health testing to youths at emergency shelters, was convicted of Medicaid fraud for a claim he submitted for a patient’s treatment. The patient had in fact been treated by the practice and no one doubts the Doc had the right to submit the claim. But the government argues that Dr Dubin overbilled for the treatment provided, and that ran afoul of § 1028A.

Dr. Dubin did not commit identity theft in any normal sense. No Argentina steaks, no Kazakh tires. But the statute’s language, the government argues, means that the Doc’s conduct “squarely fits” within the statutory text: As SCOTUSBlog put it, the government contends that “he ‘used’ the patient’s name ‘in relation to’ health care fraud, and he ‘plainly acted’ without ‘lawful authority’ when he committed the fraud.”

Dubin’s lawyers argue that the statutory phrase ‘in relation to’ must be read in tandem with the verb ‘uses.’ Dubin contends that the statute “requires a meaningful nexus between the employment of another’s name and the predicate offense.” Using another’s identity “without lawful authority” requires a showing that the defendant used another’s person’s name “without permission that was lawfully acquired.”

Dubin’s lawyers argue that the statutory phrase ‘in relation to’ must be read in tandem with the verb ‘uses.’ Dubin contends that the statute “requires a meaningful nexus between the employment of another’s name and the predicate offense.” Using another’s identity “without lawful authority” requires a showing that the defendant used another’s person’s name “without permission that was lawfully acquired.”

The 5th Circuit ruled for the government, and on rehearing the case en banc, upheld the conviction by a razor-thin 9-8 margin.

Writing in Reason, Berkeley law professor Orin Kerr said that “the stakes are high. A lot of crimes are technically felonies under Title 18 but are pretty low-level felonies, the kind of thing likely to lead to probation or at most a short prison term. But if § 1028A applies, it tacks on a two-year prison sentence. So you could have a probation offense that becomes a two-years-in-jail offense if § 1028A is triggered, with the § 1028A punishment dwarfing the predicate felony punishment.”

SCOTUS Relists Grants Safety-Valve Cert Petition: [Update]: The Supreme Court granted certiorari to Pulsifer v. United States on February 27. The case will be argued next fall].

The drug safety-valve statute, 18 USC 3553(f), provides that a sentencing court may ignore drug mandatory minimums if (among other requirements) it finds that the defendant does not have (A) more than 4 criminal history points, excluding any criminal history points resulting from a 1-point offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines; (B) a prior 3-point offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines; and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines.

Pulsifer v. United States and Palomares v. United States ask whether a defendant is ineligible for safety valve relief from the mandatory minimum if his or her criminal history runs afoul of any one of the disqualifying criteria or only if his or her criminal history runs afoul of all three disqualifying criteria, subsections (A), (B), and (C). Circuits are divided on the issue 3-4. John Elwood of SCOTUSBlog predicts that of the two cases, “probably at least one will get the grant.”

Pulsifer v. United States and Palomares v. United States ask whether a defendant is ineligible for safety valve relief from the mandatory minimum if his or her criminal history runs afoul of any one of the disqualifying criteria or only if his or her criminal history runs afoul of all three disqualifying criteria, subsections (A), (B), and (C). Circuits are divided on the issue 3-4. John Elwood of SCOTUSBlog predicts that of the two cases, “probably at least one will get the grant.”

Last week, the 4th Circuit joined the debate, holding in United States v. Jones that a defendant has to lose on all three criteria before he or she can be denied the safety valve. The Circuit said, “Ultimately, whether or not this is a prudent policy choice is not for the judiciary to decide: that determination lies solely with the legislative branch. And “the Government’s request that we rewrite 3553(f)(1)’s ‘and’ into an ‘or’ based on the absurdity canon is simply a request for a swap of policy preferences… We cannot “rewrite Congress’s clear and unambiguous text” simply because the Government believes it is better policy for the safety valve to apply to fewer defendants.

Dubin v. United States, Case No 22-10 (oral argument Feb 27, 2023)

SCOTUSBlog.com, Literalism vs. lenity in a case on the scope of federal identity theft (February 24, 2023)

Reason, Thoughts on Dubin v. United States and the Aggravated Identity Theft Statute (February 19, 2023)

United States v. Jones, Case No 21-4605, 2023 U.S. App. LEXIS 3963 (4th Cir., February 21, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root