We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

10TH CIRCUIT RULES ON FAIR SENTENCING ACT PARAMETERS; 4TH DOUBLES DOWN ON REHAIF

The 10th Circuit last week handed down a consolidated appeal from two defendants seeking sentence reductions under the 2018 First Step Act’s grant of retroactivity for the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act (“FSA“), ruling that a prisoner is eligible to seek relief under the retroactive 2010 FSA if he or she was convicted of and sentenced for a violation of a federal criminal statute, the statutory penalties for which were modified by section 2 or 3 of the 2010 FSA, prior to August 3, 2010.

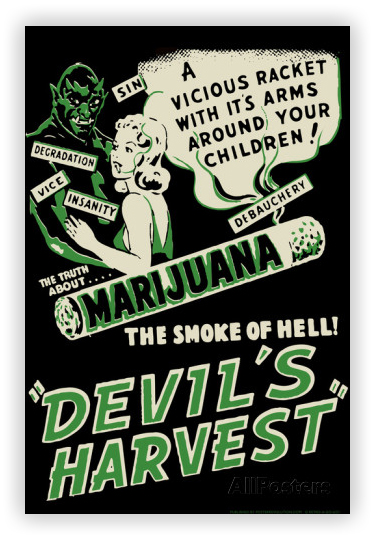

Those penalties, for those who came in late, are mandatory minimum sentences for offenses involving a certain amount of crack cocaine. Even since the crack cocaine panic of the 1980s that resulted in the Anti Drug Abuse Act of 1988, the amount of crack that would trigger a mandatory minimum sentence was one one-hundredth (1/100th) the amount of powder. In other words, that white frat boy in suburbia selling a kilo of cocaine powder got the same sentence as a black kid on a ghetto corner hawking 10 grams worth of rocks.

The FSA changed the ratio from 1:100 to 1:18 (why it did not become 1:1 is a story for another time), but its provisions were not retroactive. That meant that the crack defendant sentenced on August 2, 2010, got slammed, while the guy whose lawyer read the papers (and saw the new law about to be enacted) delayed his guy’s sentencing and got him a whopping break).

First Step finally made FSA retroactive, permitting people with pre-2010 sentences to seek sentence modifications.

One of the people seeking modification was appellants was Arthur Mannie, who complained that the district court should not have denied his FSA motion without a hearing. The Circuit disagreed, holding that a court’s jurisdiction to hear an FSA motion arises from 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(B). Neither the First Step Act nor § 3582(c)(1)(B) entitles FSA movants to a hearing, the 10th held, an FSA resentencing being fundamentally different from an initial sentencing.

The other FSA movant, Mike Maytubby, had multiple counts of conviction, only one of which was for crack. He had concurrent 151-month sentences on all of them. Because the FSA let the court adjust the term only on his crack sentence – which would not have affected the non-crack sentences – the 10th said “any reduction in the sentence of Knott’s covered offense would not actually reduce the length of his incarceration. Hence, the court cannot redress Knotts’s injury, and Knotts’s FSA motion does not present a live controversy.”

Meanwhile, the 4th Circuit has doubled down on its United States v. Gary holding that a Rehaif error is structural. In Rehaif, the Supreme Court held a year ago that in a prosecution for unlawful possession of a gun under 18 USC § 922(g), the government had to prove a defendant knew he was in the class of people the statute prohibited from possessing a gun. Early this year, the 4th Circuit held in Gary that failure to advise a defendant of that element was a structural error, that is, it was so basic a flaw that the plea could be undone even without proving the failure prejudiced the defendant.

Meanwhile, the 4th Circuit has doubled down on its United States v. Gary holding that a Rehaif error is structural. In Rehaif, the Supreme Court held a year ago that in a prosecution for unlawful possession of a gun under 18 USC § 922(g), the government had to prove a defendant knew he was in the class of people the statute prohibited from possessing a gun. Early this year, the 4th Circuit held in Gary that failure to advise a defendant of that element was a structural error, that is, it was so basic a flaw that the plea could be undone even without proving the failure prejudiced the defendant.

Gary is a real outlier. Every other circuit that has considered it requires a defendant to show that if he had been advised properly, he would have gone to trial. In the 4th, Gary holds that the mistake alone is enough for a defendant to carry the day.

The 4th Circuit denied the government rehearing on Gary, but there is little doubt it will go to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, last week, the Circuit held that even where a defendant was indicted and went to trial, a Rehaif error requires that the 922(g) verdict be set aside (even where it is pretty clear that the defendant would have been found guilty if there had been no error).

The Circuit held that the indictment’s omission of the element and the judge’s failure to instruct the jury on the missing element were both plain error, no matter that the defendant was probably guilty anyway. “Were this Court to affirm this conviction simply to avoid burdening the criminal justice system, we would diminish the public faith in the integrity of our courts. What gives people confidence in our justice system is not that we merely get things right… Rather, it is that we live in a system that upholds the rule of law even when it is inconvenient to do so.”

While rejecting the 4th Circuit’s “structural error” approach, the 7th Circuit last week decided that Blair Cook was entitled to a new trial. Blair, a pot fan, was convicted of a 922(g) offense for carrying a gun while being an unlawful drug user. The Circuit set aside the verdict, because the jury had not been given the Rehaif instruction. “The error in this case relieved the government of the burden of proving an essential element of offense beyond a reasonable doubt,” the 7th said. “The error was not so fundamental that it qualifies as structural. Nonetheless, it was a serious error, in the sense that it both omitted a key element of the government’s case and deprived Cook of the right to have the jury assess the sufficiency of that evidence as to that element.”

While rejecting the 4th Circuit’s “structural error” approach, the 7th Circuit last week decided that Blair Cook was entitled to a new trial. Blair, a pot fan, was convicted of a 922(g) offense for carrying a gun while being an unlawful drug user. The Circuit set aside the verdict, because the jury had not been given the Rehaif instruction. “The error in this case relieved the government of the burden of proving an essential element of offense beyond a reasonable doubt,” the 7th said. “The error was not so fundamental that it qualifies as structural. Nonetheless, it was a serious error, in the sense that it both omitted a key element of the government’s case and deprived Cook of the right to have the jury assess the sufficiency of that evidence as to that element.”

United States v. Mannie, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 26192 (10th Cir Aug 18, 2020)

United States v. Medley, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 26721 (4th Cir. Aug 21, 2020)

United States v. Cook, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 26023 (7th Cir. Aug 17, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root