We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

GUNDY – NO BANG BUT A WHIMPER

As soon as the Supreme Court announced yesterday that it had affirmed the 2nd Circuit by an 8-1 vote, I knew that the Justices had massaged the case – which was argued the first week of October 2018 – until they reduced the holding to something narrow enough that they could almost all agree.

Petitioner Herman Gundy, a convicted sex offender, was convicted of failing to register under the Sex Offenders Registration and Notification Act. He had been convicted of the sex offense before SORNA passed, but Congress included in the bill a directive to the Attorney General to “specify the applicability” of SORNA’s registration requirements and “to prescribe rules for [their] registration.”

Petitioner Herman Gundy, a convicted sex offender, was convicted of failing to register under the Sex Offenders Registration and Notification Act. He had been convicted of the sex offense before SORNA passed, but Congress included in the bill a directive to the Attorney General to “specify the applicability” of SORNA’s registration requirements and “to prescribe rules for [their] registration.”

Under that delegated authority, the Attorney General issued a rule specifying that SORNA’s registration requirements apply in full to pre-Act offenders. This made Herman’s failure to register a crime. Both the District Court and the Second Circuit rejected Herman’s claim that Congress unconstitutionally delegated legislative power when it authorized the Attorney General to essentially determine what act or non-act constituted a crime.

Gundy was considered to be a big case, because the laxity with which Congress has delegated authority to the Executive Branch to make crimes cuts a broad swath across the law. The DEA has the power to declare an analogue drug to be a controlled substance. The ATF has the power to declare a little bent piece of metal a “machinegun” because it can be inserted into an AR-15 to make it fire on full auto. In fact, there are over 1,500 regulations enacted by Executive Branch agencies that carry criminal consequences.

Many observers thought Gundy could be a watershed, a moment when the Court would finally say “enough” to the willy-nilly delegation of power without limits. The fact that SCOTUS has taken so long to decide an early-term case suggested that there was a lot of dissention among the Justices, and that the decision, when it finally came, would be a whopper.

No such luck. Instead the Justices parsed the history of SORNA, and found that Congress had always meant for SORNA’s registration requirements to apply to pre-Act offenders, based on the Act’s statutory purpose, its definition of sex offender, and its history. But Congress was afraid that registering so many people right away would not be feasible. SORNA, the Court said, created a “practical problem[ ]” because it would require “newly registering or reregistering a large number of pre-Act offenders.”

Congress therefore asked the Attorney General, who was already charged with responsibility for SORNA implementation, to examine the issues and to apply the new registration requirements accordingly.” On that understanding, the Court said, the “Attorney General’s role… was important but limited: It was to apply SORNA to pre-Act offenders as soon as he thought it feasible to do so.”

There, the Court said. The AG only did what Congress clearly wanted done. Problem solved.

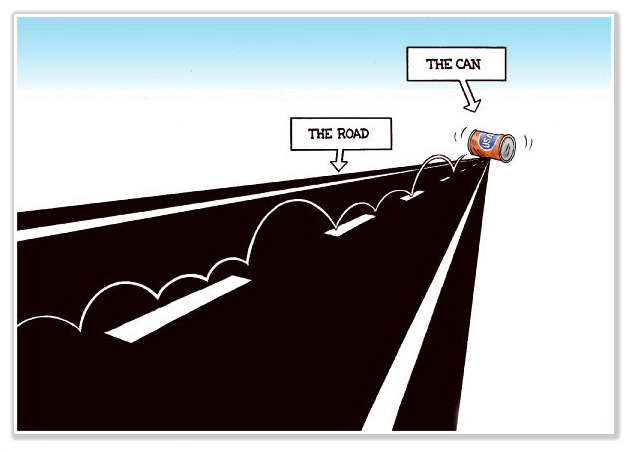

What really happened is the Court was able to find justification in this instance for the AG doing what he did, rather than addressing the broader question. (Of course, lurking beneath the surface was the unspoken fear that declaring anything that pummels sex offenders to be unconstitutional would unleash a maelstrom of media and social criticism of the Court). Whatever the reason, the Court’s punt leaves the broader delegation doctrine question, which is as important as it is dry, for another day.

What really happened is the Court was able to find justification in this instance for the AG doing what he did, rather than addressing the broader question. (Of course, lurking beneath the surface was the unspoken fear that declaring anything that pummels sex offenders to be unconstitutional would unleash a maelstrom of media and social criticism of the Court). Whatever the reason, the Court’s punt leaves the broader delegation doctrine question, which is as important as it is dry, for another day.

Gundy v. United States, Case No. 17-6086 (Supreme Court, June 20, 2019)

CLOCKWATCHERS

Another SCOTUS decision yesterday was a sleeper, one I had paid scant attention to. But it is a useful holding nonetheless.

A lot of people who were unlawfully treated before and during their criminal cases, and may have good legal issues against the people responsible, end up getting shut out by the statute of limitations. That happened to Ed McDonough.

Ed was an election commissioner in Troy, New York. After questions arose, Youel Smith was specially appointed to prosecute a case of forged absentee ballots in that election. Ed became his primary target.

Ed alleged that Youel fabricated evidence against him and used it to secure a grand jury indictment. Youel tried the case, using the allegedly false evidence, Ed got a mistrial the first time, but an outright acquittal the second.

Ed alleged that Youel fabricated evidence against him and used it to secure a grand jury indictment. Youel tried the case, using the allegedly false evidence, Ed got a mistrial the first time, but an outright acquittal the second.

Ed sued Youel under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, asserting a claim for fabrication of evidence. The district court dismissed the claim as untimely, and the 2nd Circuit affirmed. The courts both held that the 3-year limitations period began to run when Ed learned that the evidence was false, which undisputedly occurred by the time Ed was arrested and stood trial.

The Supremes reversed, ruling for Ed. The fabrication claim was a lot like a malicious prosecution claim, and such a claim does not arise until the defendant is acquitted. To follow the lower courts’ holding would create practical problems in places where prosecutions regularly last nearly as long as — or even longer than—the limitations period. Criminal defendants, SCOTUS said, “could face the untenable choice of letting their claims expire or filing a civil suit against the very person who is in the midst of prosecuting them. The parallel civil litigation that would result if plaintiffs chose the second option would run counter to core principles of federalism, comity, consistency, and judicial economy.”

McDonough v. Smith, Case No. 18–485 (Supreme Court, June 20, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root