We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

INTRACTABLE PROBLEMS LOOM ON FAIR SENTENCING ACT RESENTENCINGS

A good number of crack defendant resentencings have breezed through district courts since the First Step Act authorized the retroactive application of the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act (“FSA”) to people sentenced for crack prior to August 2010.

The concerns of a few dissident district judges, however, may be gaining traction, jeopardizing future FSA resentencings.

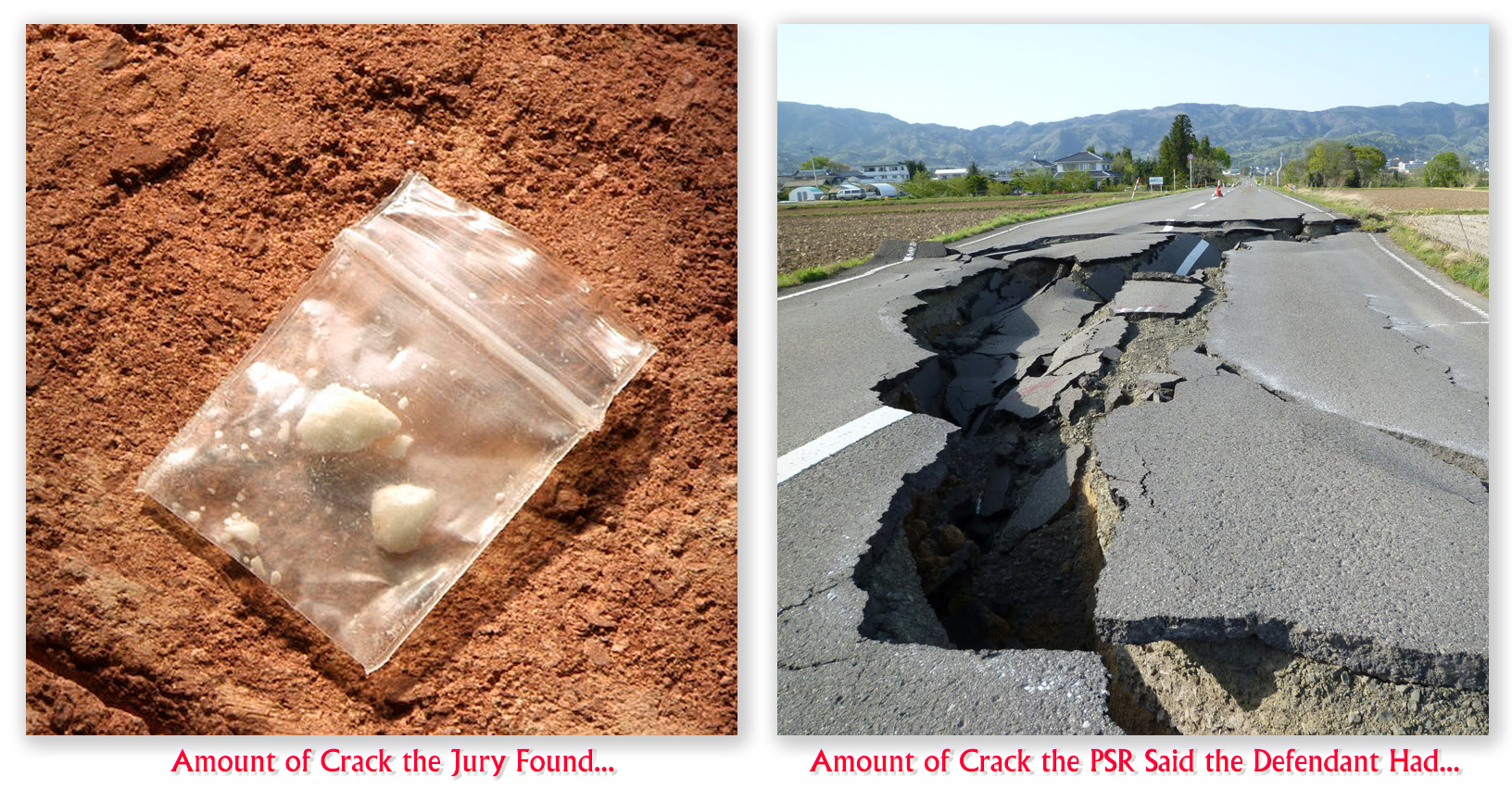

The problem is this: Just about all of the pre-FSA indictments alleged the defendant had “five or more” or “fifty or more” grams of crack. Back then, five or more bought a defendant a minimum 5 years, while 50 or more was good for a 10-year minimum. But what the indictment alleges is one thing. What the presentencing report says is something else altogether, and the PSR’s amount of drugs (used for setting the Guidelines range) is what the district court usually finds.

The problem is this: Just about all of the pre-FSA indictments alleged the defendant had “five or more” or “fifty or more” grams of crack. Back then, five or more bought a defendant a minimum 5 years, while 50 or more was good for a 10-year minimum. But what the indictment alleges is one thing. What the presentencing report says is something else altogether, and the PSR’s amount of drugs (used for setting the Guidelines range) is what the district court usually finds.

On FSA resentencings, some defendants have convinced courts that if the indictment said “five or more grams” of crack, for instance, their sentences should be based on five grams. Some sentences have fallen dramatically as a result.

Dan Blocker argued to his judge that when a defendant seeks an FSA sentence reduction, the relevant question is not how much crack was involved in the offense, but instead only how much was charged in the indictment.

Some other courts have grappled with this argument, but Dan’s court took it by the horns. In an interim decision, the district court complained Dan’s approach – the “indictment-controls” theory – “misreads the statute and is demonstrably inconsistent with Congress’s intent.” The district judge said the First Step Act specified that a sentence reduction is allowed only for a “covered offense,” that is, “a violation of a Federal criminal statute…” Violation of the statute is the criminal conduct, the court said, not the indictment. Thus, the court must follow the offense-controls theory, not the indictment-controls theory.

The court said the question is what sentence would have been imposed had the FSA been in effect when Dan sold the crack. The answer, the court held, does not turn on what the actual indictment charged, but rather on what it would have charged had the FSA governed the case. The court speculated that if the FSA had been in effect, Count 1 would have charged that the conspiracy involved 280 grams or more, not just 50, and other counts would have charged the higher amounts – 28 grams and 280 grams – listed in the FSA. “The only reason the actual indictment used the lower amounts,” the court said, “was that those were the amounts included in the statute at that time – the indictment tracked the statute.”

The higher amounts might have affected Dan’s decision to plead guilty, the court said, thus requiring a hearing to figure out what Dan might have done in response to what the indictment might have said.

If what the indictment in a pre-August 2010 crack said controlled resentencing, the court complained, “every crack defendant sentenced before the Fair Sentencing Act took effect would be eligible for a reduction…” and the First Step Act would “provide a windfall sentence reduction to pre-August 2010 defendants that people sentenced after 2010 would not get. “Congress could not have intended to treat crack defendants this much more favorably than powder defendants.

The so-called offense controls theory will almost certainly be appealed. Major appeals questions about retroactive FSA resentencings, even if resolved in the defendants’ favors, are likely to result in inconsistent circuit decisions, and could tie up resentencings for a year or better.

United States v. Blocker, 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 79934 (N.D.Fla., Apr. 25, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root