We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

IF AT FIRST YOU DON’T SUCCEED…

At their first sentencing, the Vera brothers watched as the Government established the drug amounts implicated in their case for sentencing purposes through an FBI agent who “interpreted” the contents of wiretapped phone conversations to conjure up a drug weight. Drug weight, of course, drives the base offense levels of the Sentencing Guidelines – a kilo of meth will buy you a much higher sentencing range that a blunt of Mary Jane in your back pocket.

The district court accepted the agent’s white-bread explanations of the purported code being used in the phone conversations, and hammered Armando with 360 months and his brother with 262.

The district court accepted the agent’s white-bread explanations of the purported code being used in the phone conversations, and hammered Armando with 360 months and his brother with 262.

After the 9th Circuit threw that out, the brothers were resentenced. This time, the Government – fearful of the FBI “translator” gambit – relied instead on the contents of co-conspirators’ plea agreements to establish drug quantities attributable to the Vera brothers.

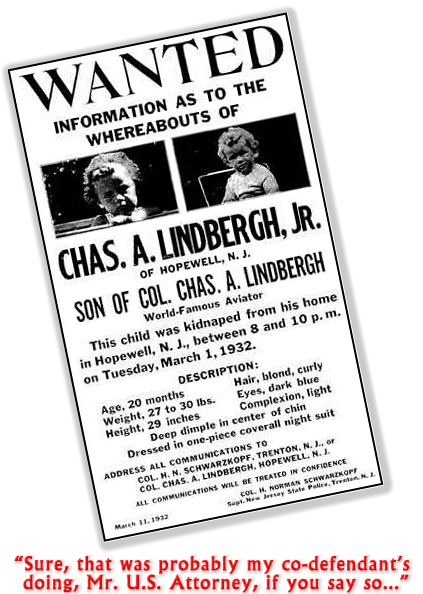

Anyone who has been in a federal courthouse for any purpose other than to use the restrooms knows that the government dictates the contents of a plea agreement, and as long as the language in implicating someone else, a defendant will happily sign on. Paragraph 5 says a co-defendant kidnapped the Lindbergh baby? Why not? Despite the fact that using a plea agreement with Defendant A as sentencing evidence for Defendant B is like the government quoting itself, the district court found the approach “more credible” than the PSR and Armando’s sentencing memorandum, because it was the “least dependent on interpretation of the recordings” as well as the government’s “single most significant data source.”

Last week, the 9th Circuit reversed the Vera brothers’ second sentencing, too. The panel held that the district court relied too heavily upon co-conspirator plea agreements to determine drug quantities, mistaking holding that the plea agreement statements were reliable statements against interest under F.R.Ev. 804(b)(3). The panel said “a defendant signing a plea agreement may adopt facts that the government wants to hear in exchange for some benefit, usually a lesser sentence. In pointing their fingers at the Vera brothers, the co-conspirators were acknowledging neither their own guilt nor conduct that would necessarily enhance their own sentences. Rather, these statements merely helped the government’s prosecution of the Veras.” Due to a co-defendant’s strong motivation to implicate the defendant and to exonerate himself, any statements “about what the defendant said or did are less credible than ordinary hearsay evidence.”

Last week, the 9th Circuit reversed the Vera brothers’ second sentencing, too. The panel held that the district court relied too heavily upon co-conspirator plea agreements to determine drug quantities, mistaking holding that the plea agreement statements were reliable statements against interest under F.R.Ev. 804(b)(3). The panel said “a defendant signing a plea agreement may adopt facts that the government wants to hear in exchange for some benefit, usually a lesser sentence. In pointing their fingers at the Vera brothers, the co-conspirators were acknowledging neither their own guilt nor conduct that would necessarily enhance their own sentences. Rather, these statements merely helped the government’s prosecution of the Veras.” Due to a co-defendant’s strong motivation to implicate the defendant and to exonerate himself, any statements “about what the defendant said or did are less credible than ordinary hearsay evidence.”

Hearsay is admissible at sentencing, so long as it is accompanied by “some minimal indicia of reliability.” But here, the district court’s primary rationale for relying upon the plea agreements was Evidence Rule 804(b)(3). The Circuit ruled that a district court may not rely solely on Rule 804(b)(3) to use non-self-inculpatory statements in a co-conspirator’s plea agreement to determine a defendant’s drug-quantity liability.

United States v. Vera, Case No. 16-50634 (9th Cir. June 25, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root