We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

RIGHT EVIDENCE BUT WRONG INSTRUCTION IS NOT GOOD ENOUGH ON 2255

People convicted of drug trafficking can get a greatly increased minimum sentence, up to natural life, if the government proves that drugs they distributed caused the death of a user. Up until a few years ago, this provision – 21 USC 841(b)(1)(A) – was a great bludgeon for the government, which was winning enhanced sentence just by showing that someone who died had taken drugs sold by the defendant, no matter how many other things they might have taken, too.

People convicted of drug trafficking can get a greatly increased minimum sentence, up to natural life, if the government proves that drugs they distributed caused the death of a user. Up until a few years ago, this provision – 21 USC 841(b)(1)(A) – was a great bludgeon for the government, which was winning enhanced sentence just by showing that someone who died had taken drugs sold by the defendant, no matter how many other things they might have taken, too.

We saw one case where a woman died when she nodded off at the wheel and drove off the road, hitting a tree. She was legally drunk, but also had marijuana and oxycontin in her system. The guy who sold her the oxy got a minimum 20 years.

In 2014, common sense prevailed in Burrage v. United States, when the Supreme Court held that unless the government could prove that “but for” the drugs sold by the defendant, the user-death enhancement could not be applied. In our drunk-driving case above, the defendant got a sentence reduction because no one could testify that without the oxy, our drunk driver would have stayed on the road. But as Lorenzo Roundtree found out last week, Burrage has its limits.

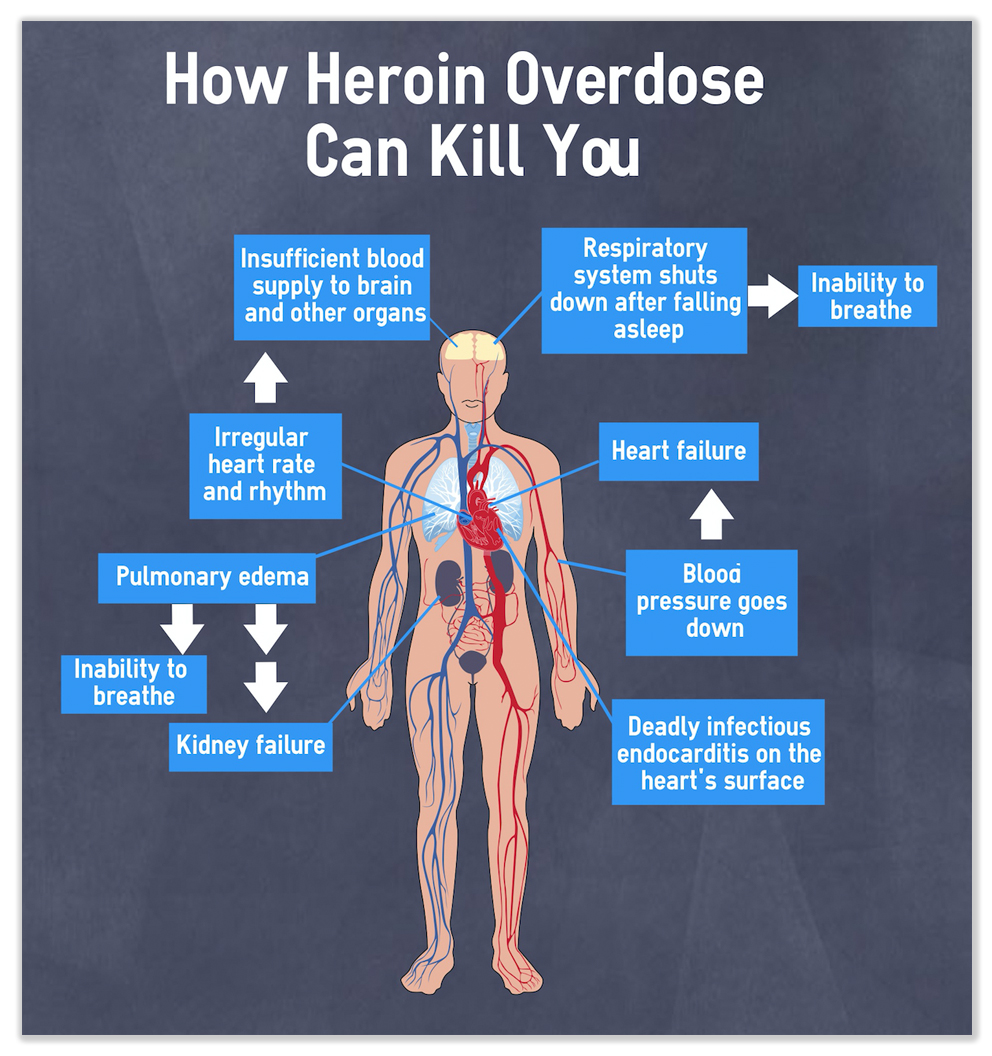

Lorenzo sold heroin to some people who shared their smack with the victim. Shortly after using the heroin, the drunk victim became unresponsive and died. The medical examiner testified that he died as a result of alcohol and drug intoxication. The judge instructed the jury that if it found the heroin contributed to the victim’s death, that was enough, even if it was not the primary cause of death.

After Burrage, that instruction was no longer good law. (In fact, Burrage said the instruction had never been good law). Lorenzo had a 28 USC 2255 on file when Burrage was handed down, so he amended it to claim that his jury instructions were flawed. Last week, the 8th Circuit turned him down.

Lorenzo’s problem was that a medical examiner testified for the government that the alcohol and heroin had worked together, “synergistically” as the doc put it, to depress the victim’s respiratory system. No one contradicted the doctor’s opinion that the percent of alcohol found in the victim’s bloodstream, 0.16%, was not enough to cause death “if that were the only thing that was in his blood.” The doctor testified the alcohol and morphine “probably worked together,” but “the morphine alone could have caused his death.”

The Circuit held that based on doctor’s uncontradicted testimony, “the incorrect jury instruction did not result in prejudice” to Lorenzo. The doc’s opinion that “the morphine alone could have caused the victim’s death” would be enough to let the jury to find that Lorenzo’s drugs were an “independently sufficient cause of the victim’s death,” as Burrage required. What’s more, the 8th said, because the heroin and liquor “worked synergistically to cause” the victim’s death, but the amount of alcohol alone in the victim’s bloodstream was not enough to cause death, any reasonable jury would have found that the heroin was a “but-for” cause of the victim’s death. Therefore, Lorenzo was not harmed by the bad jury instruction, because if the jury had been properly instructed, it would have found Lorenzo qualified for his natural life sentence anyway.

The Circuit held that based on doctor’s uncontradicted testimony, “the incorrect jury instruction did not result in prejudice” to Lorenzo. The doc’s opinion that “the morphine alone could have caused the victim’s death” would be enough to let the jury to find that Lorenzo’s drugs were an “independently sufficient cause of the victim’s death,” as Burrage required. What’s more, the 8th said, because the heroin and liquor “worked synergistically to cause” the victim’s death, but the amount of alcohol alone in the victim’s bloodstream was not enough to cause death, any reasonable jury would have found that the heroin was a “but-for” cause of the victim’s death. Therefore, Lorenzo was not harmed by the bad jury instruction, because if the jury had been properly instructed, it would have found Lorenzo qualified for his natural life sentence anyway.

Roundtree v. United States, Case No. 16-3298 (8th Cir. Mar. 22, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root